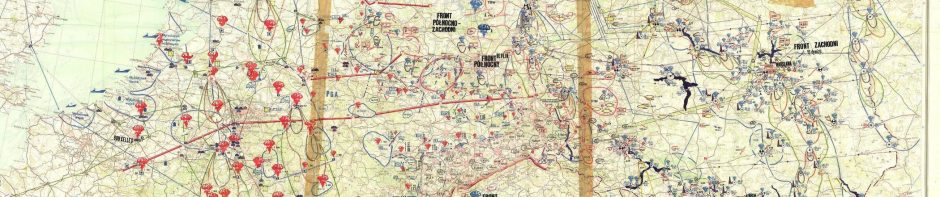

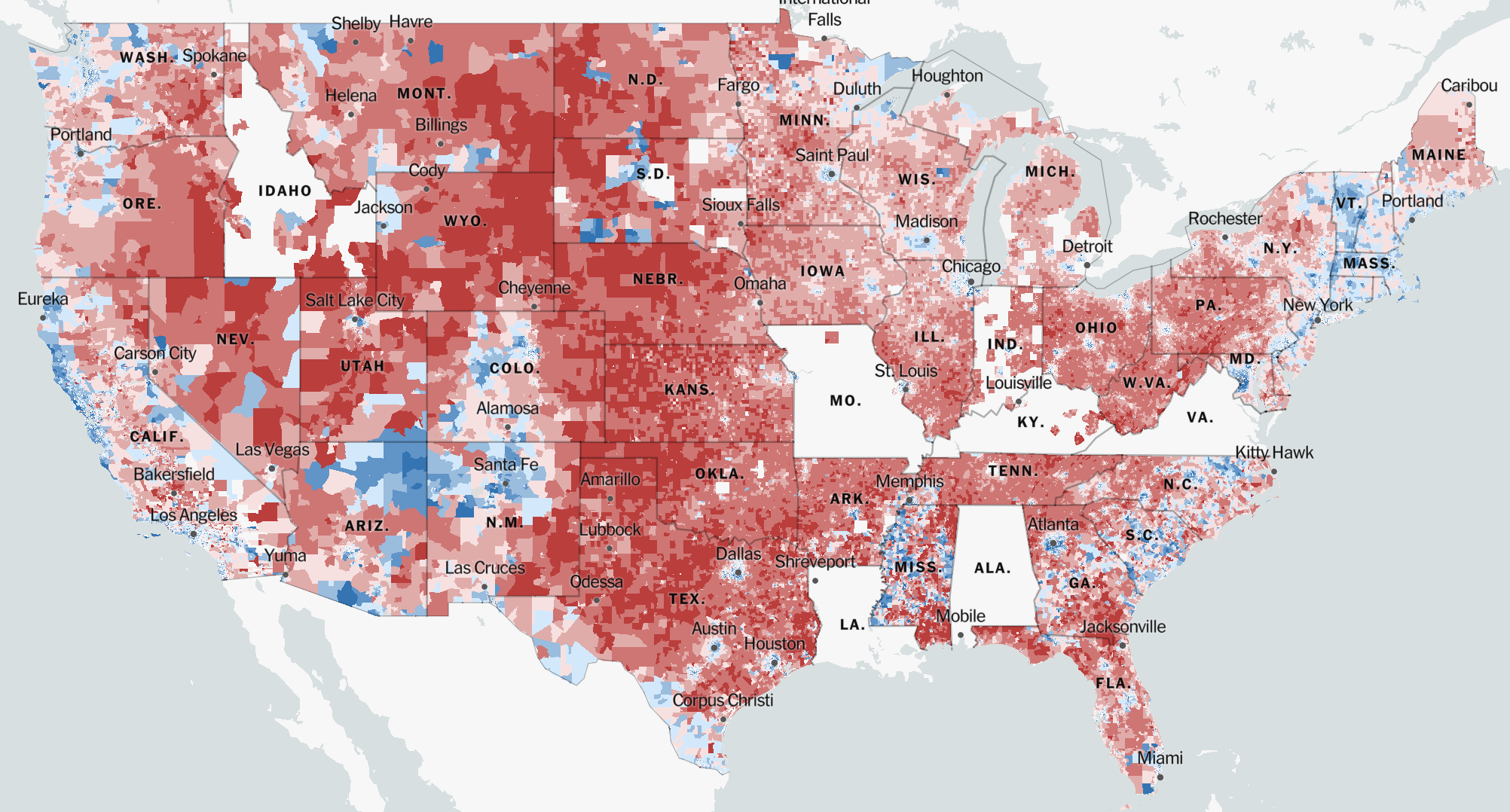

FIGURE 1: 2020 Presidential Election (Park et al., “An Extremely Detailed Map of the 2020 Election”)

FIGURE 1: 2020 Presidential Election (Park et al., “An Extremely Detailed Map of the 2020 Election”)

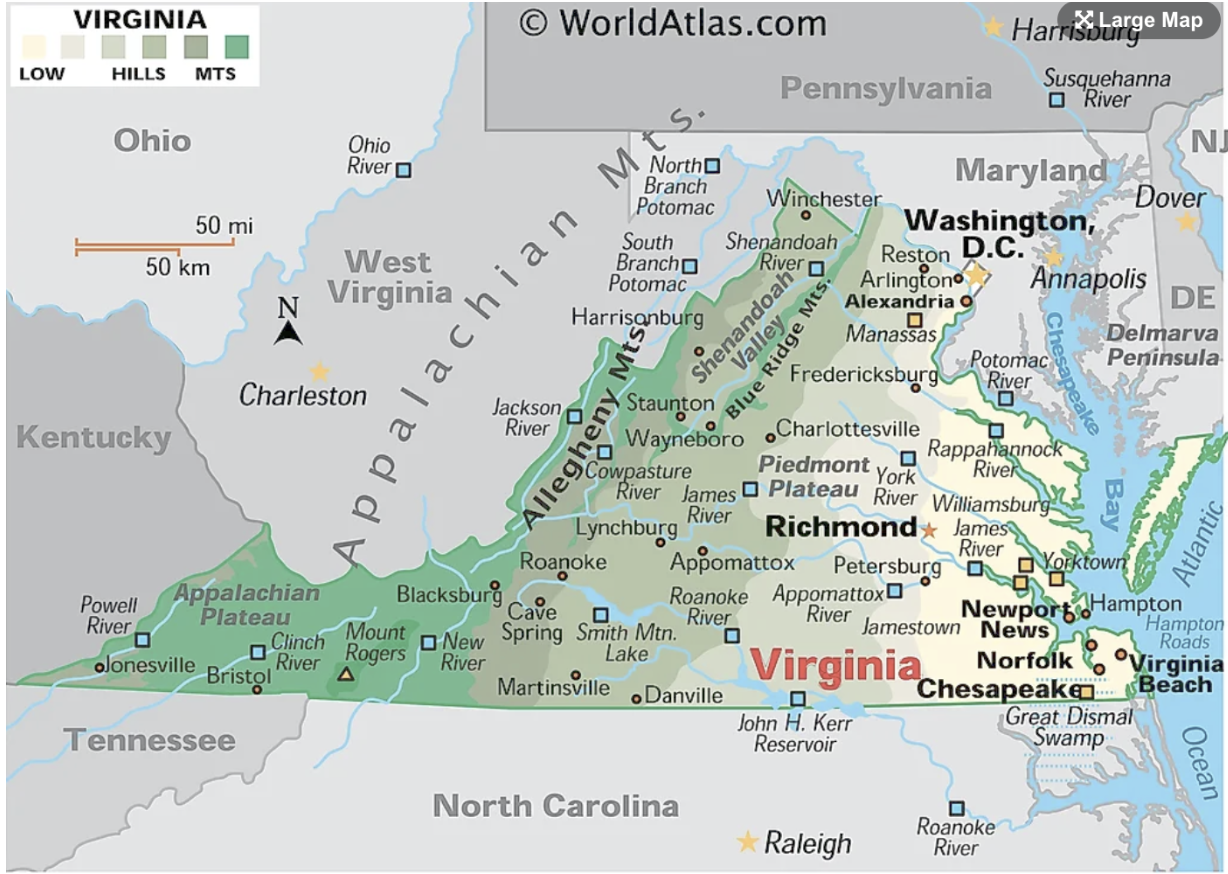

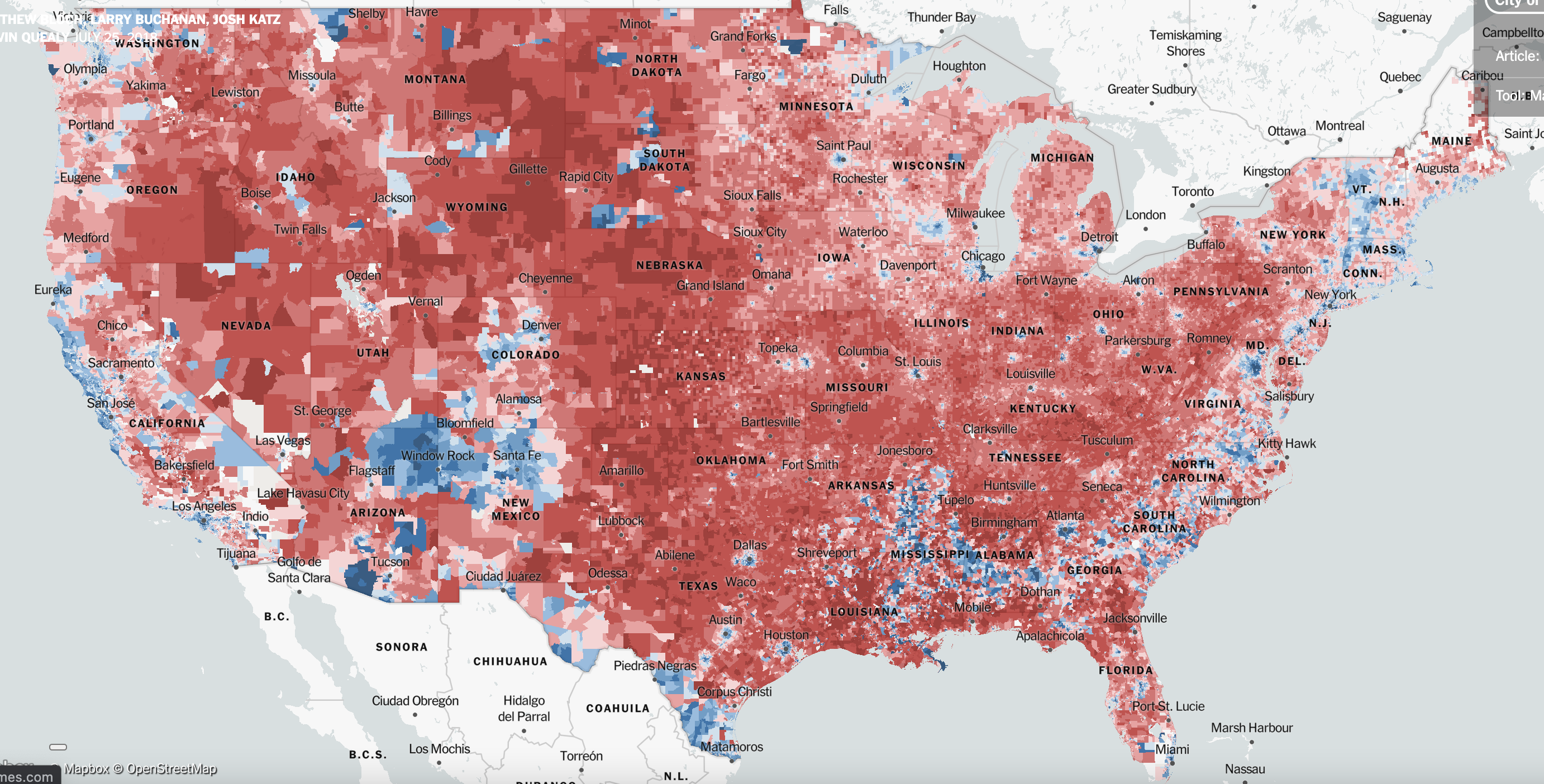

FIGURE 2: 2016 Presidential Election (Bloch et al., “An Extremely Detailed Map of the 2016 Presidential Election”)

FIGURE 2: 2016 Presidential Election (Bloch et al., “An Extremely Detailed Map of the 2016 Presidential Election”)

To preface this blog post, I would like to note that I do not mean what I say to be taken as a political message. The background I provide on this topic is worded as such to allow for a deeper conveyance of my argument related to my map of the week and around the rhetoric of cartography.

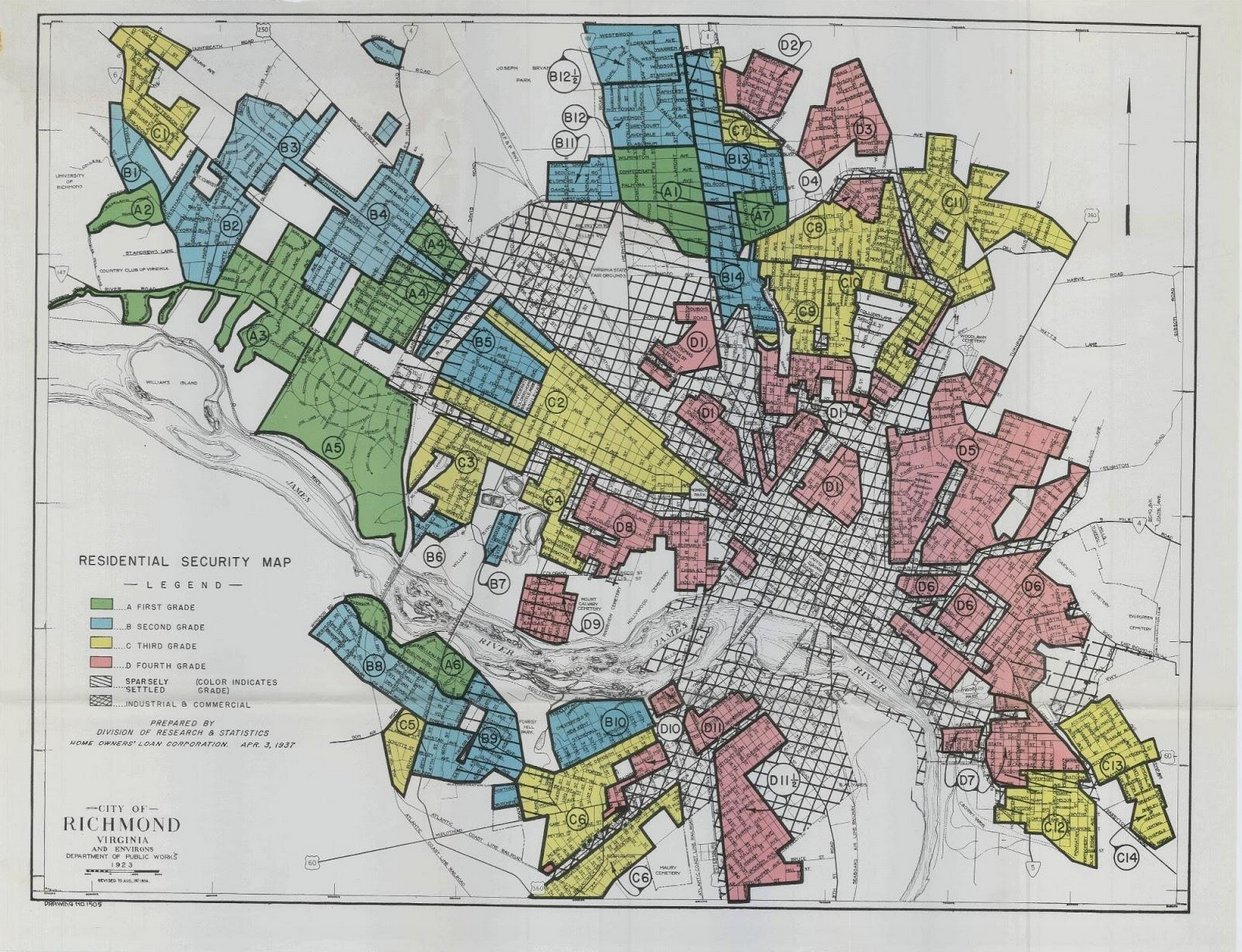

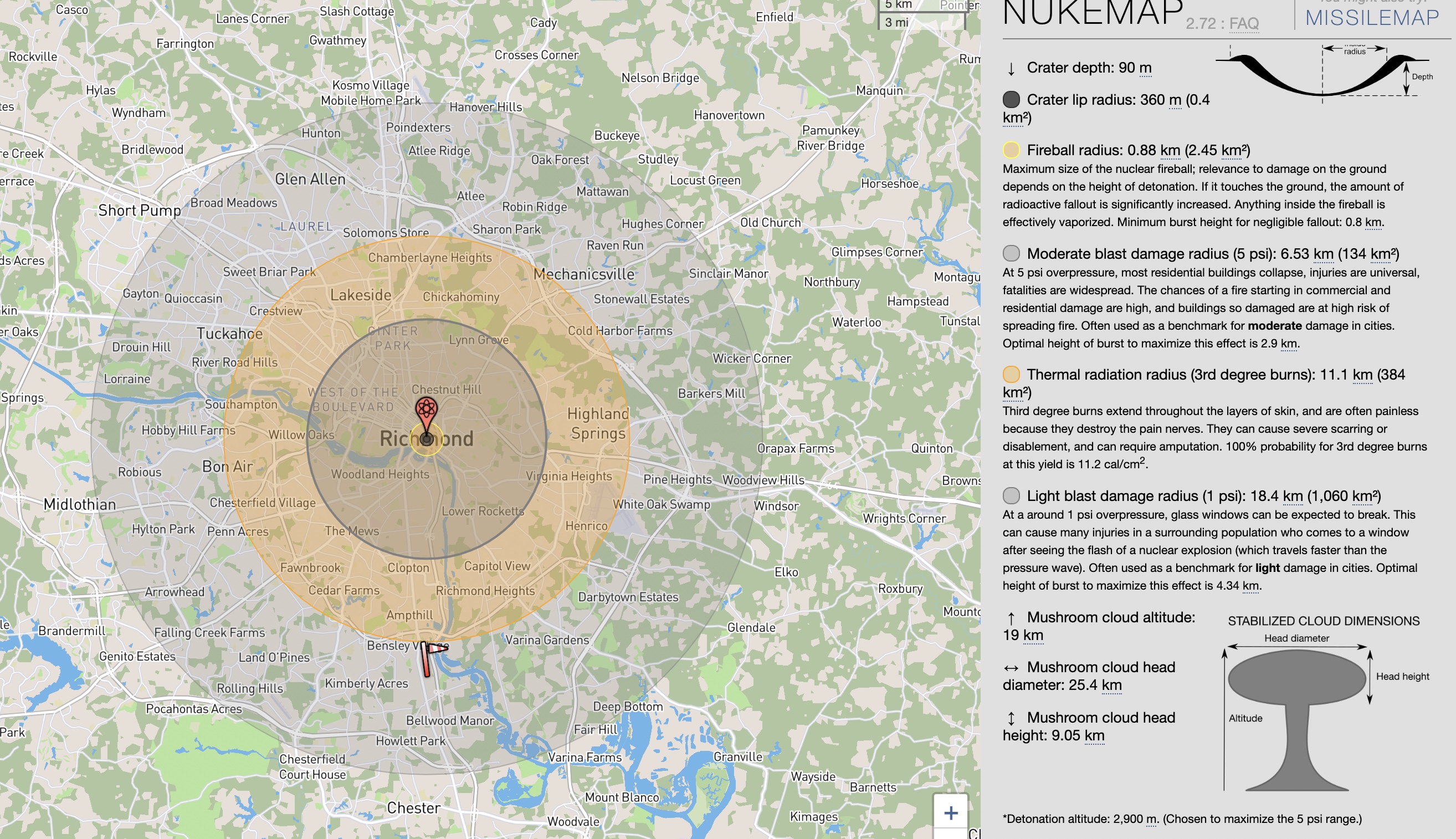

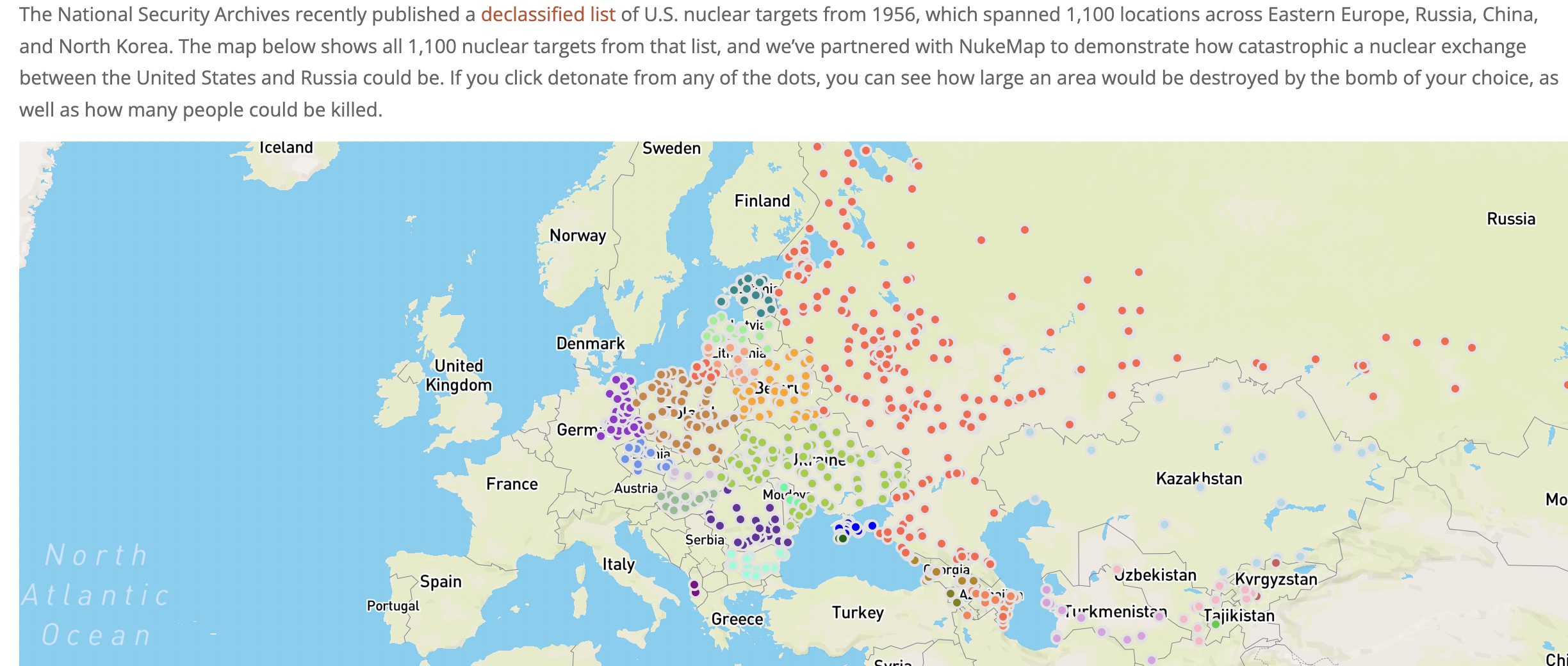

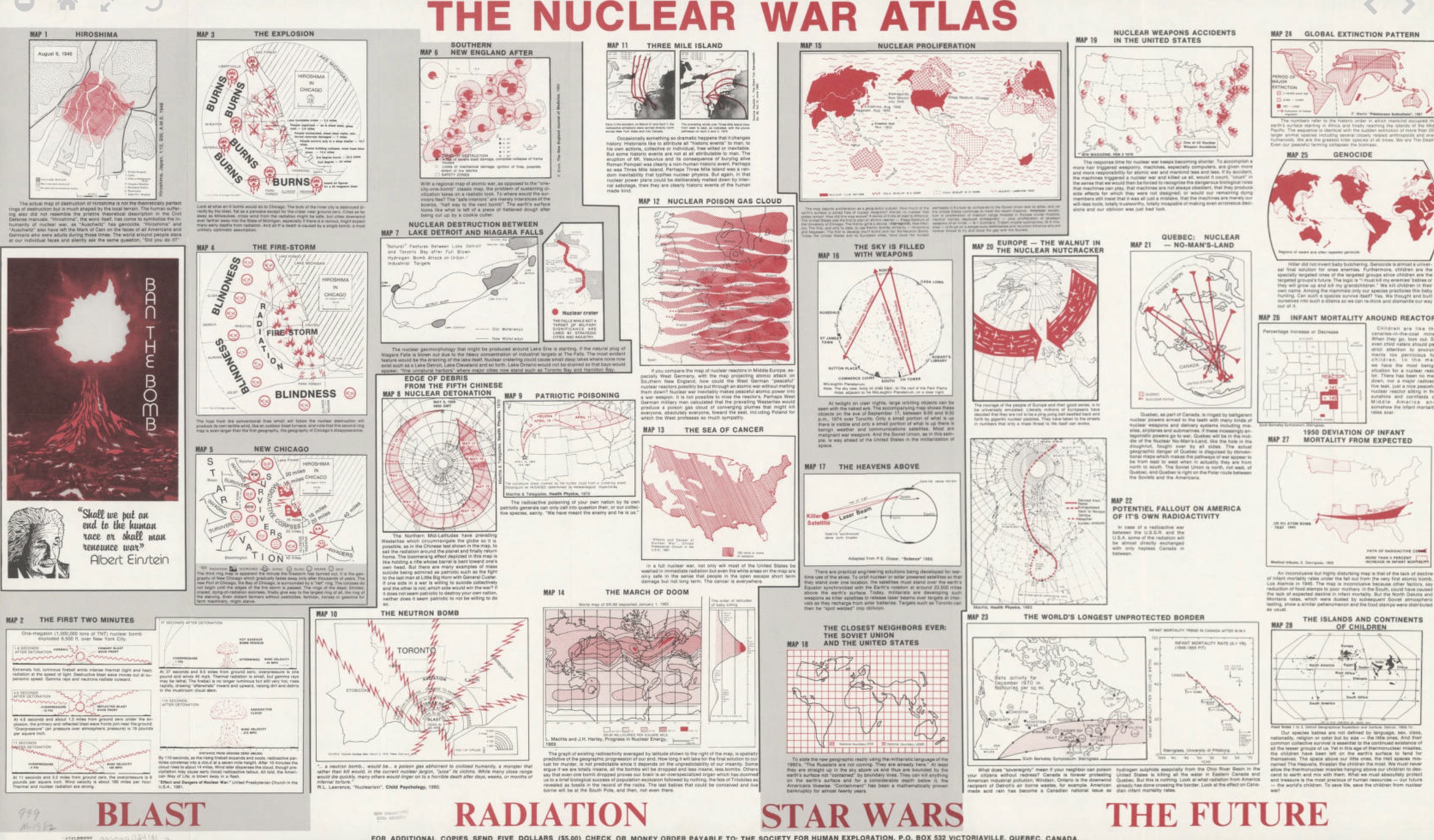

The map I chose for my blog is a map of the 2020 election results (FIGURE 1). The map details data from “2,523 of 3,143 counties in 47 states, representing 89% of all votes cast” (Park et al., “An Extremely Detailed Map of the 2020 Election”). I chose this map to be my “map of the week” because I think political maps are great examples of the rhetoric behind cartography. Not only that, but I believe this map and my greater analysis complement the blog thread as American political maps offer additional avenues of analysis on the rhetorical weight of their standing.

There are some states that have been omitted from the county breakdown on the 2020 election map due to the ways the states reported votes. Through the pandemic, some states didn’t report votes in ways that linked the votes to specific precincts in the state because of the widespread mail-in balloting, so the New York Times – which is the source that created the map – felt that country-specific data from those states could not reliably be mapped. Due to this issue, the visualizations of the map as a whole are affected by the omitted counties and states. I wanted to mention this because while my analysis will be on the context and mapping of the 2020 election, after digging around I found that the 2016 election map and 2020 election map are nearly identical from a visual standpoint. So, in an effort to get around the visual issue of the 2020 map’s omission of certain counties and states, for some of my overarching analytical points about the rhetoric of cartography, I will reference the New York Times’ detailed map of the 2016 election (FIGURE 2).

Before I continue, I would like to present a question to you that I would like you to keep in the back of your mind as you read on: In the ways maps visualize information, how might a [political] map display, or distort the prevalence of political tension in the represented society?

With that question stated, I will now provide some historical context behind the map. On November 3, 2020, the United States presidential election between former Vice President Joe Biden (D) and incumbent President Donald Trump (R) was decided, in which Joe Biden was elected as the 46th President of the United States. His victory marked the history books as the fifth occurrence in the past 100 years where the incumbent president did not win their re-election campaign. This monumental election also logged the highest voter turnout by percentage since 1900 (Park, “2020 Voter Turnout Was the Highest the U.S. Has Seen in Over a Century”), in which Biden earned his victory by outscoring Trump in both the electoral vote category (Biden with 306 and Trump with 232) and popular vote category (Biden with 81.2 million and Trump with 74.2 million) (“Presidential Election, 2020”).

Following the deliverance of the votes of the Electoral College, a joint session of the Congress was scheduled to take place on January 6, 2021, in which one of the most unprecedented events in recent history occurred. A large mass of American citizens incited violence against the Government of the United States through an insurrectionist invasion of the United States Capitol building. This event was largely provoked by Trump, which contested one of the most important and central tenets of American democracy, the need for a peaceful transfer of power, and resulted in Trump’s [second] impeachment just one week before his term expired.

Through the course of Trump’s presidential term, he could easily be labeled as a norm-shattering president (for better or for worse). This is because a central theme in many past presidents’ rhetoric is that they contain strong elements of logos, which is a form of rhetorical persuasion that is centered around building strong logical arguments to gain appeal. However, with Trump, his rhetoric was more strongly aligned with the elements of ethos, which is a form of rhetorical persuasion that is centered around building a strong sense of status or authority to appeal to others. This can be seen through Trump’s strong visceral reactions on Twitter, in debates, and in speeches, and can also be understood through the continual maintenance of his “strongman persona” (Rowland, “The Rhetoric of Donald Trump”). Through this rhetoric, Trump was incredibly effective at reaching his intended audience and he gained powerful support from millions of Americans across the country. However, in doing so, millions of people also outspokenly opposed his rhetorical style because, to many, it felt un-presidential and intrinsically violent. As a result, Trump’s rhetoric arguably caused one of the most post-civil war hyper-partisan divides in our nation’s history.

With the historical context now provided, I will conduct a brief cross-sectional analysis of the rhetoric of cartography in relation to the 2020 election map by referencing the studies of two prevalent scholars in this field of rhetorical cartography, Dennis Wood and J. B. Harley.

In Wood’s book, The Power of Maps, he states how maps hold an “inherent indexicality to link the territory in question with what comes with it;” they have rhetorical lives (Wood and Fels, The Power of Maps). Wood goes on to explain how maps serve as ways to label politically based areas, in which the science of cartography is in contest with the foundational artistry of it. This is important to the visualization of the 2020 election map because the map shows an overwhelming portion of the United States coated in red to show Republican voters, and an underwhelming portion of the United States coated in blue to show Democratic voters. So, on the basis of territory, Trump won this election. However, on the basis of population, Biden won, which isn’t conveyed through the rhetoric of this map. This is because elections are decided by the populace, in which the most densely populated areas are cities that happen to take up small portions of geographically based territory. Furthermore, on the premise that maps serve as ways to label politically based areas, American electoral maps have an innate history of aligning space with political alignment. This can become an issue for political maps because it curtails areas on the map in ways that divide territory on a centralized, partisan basis. This causes territory to be [mis]represented through the acclaimed totality of red or blue prevalence in the area, which further feeds into nationwide tensions of political division.

In Harley’s book, Deconstructing the Map, he states how maps convey tension as both scientific documents and as political and rhetorical engines. They can legitimize power and can create or enforce inequalities (Harley, “Deconstructing the Map”). This is an important argument made by Harley for my blog post because it can be related to the storming of the capital. During the course of the election, these types of maps were broadcasted nationwide, which, when visually interpreted, show overwhelming support for Trump as massive amounts of the nation’s terrain were doused in red. I would argue that, in many ways, the map’s visual distortion of political support for Trump on a spatialized basis served as a sort of ‘factual’ justification for the [ignominious] storming of the capitol building, in which many citizens felt the results of the election did not represent their perceived ‘reality’ of the nation’s support for Biden. To connect this back to my central argument, – which is that American political maps innately present issues of divisive partisanship through the usage of space as a means to visualize the political arrangement of the nation – Harley’s point on how maps can legitimize power through the conveyed tension as both scientific documents and as political and rhetorical engines is perfectly exemplified through my statement above. Maps historically serve a purpose as being scientific documents, and in our society science and fact tend to be considered as one of the same. Tensions can therefore rise when a map is used to represent political alignment, and in the case of this map, it does so in a way that does not adequately align with the processes of determination for which it is used to convey. This map was broadcasted nationwide and was used as a means to accurately convey information on the results of the presidential election, however, the event that it was used (i.e. the presidential election) for is decided on the populace’s vote count, to which space is not factored in. So, by using a map, space is granted a greater emphasis, which directly conflicts with the use case of the map by distorting the reality of partisanship in our nation as it frames nation support based more on spatial support than on populous support.

References:

Bloch, Matthew, Larry Buchanan, Josh Katz, and Kevin Quealy. “An Extremely Detailed Map of the 2016 Presidential Election.” The New York Times, July 25, 2018, sec. The Upshot. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/upshot/election-2016-voting-precinct-maps.html.

Harley, J B. “Deconstructing the Map.” Cartographica: The International Journal for Geographic Information and Geovisualization 26, no. 2 (June 1989): 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3138/E635-7827-1757-9T53.

Park, Alice, Charlie Smart, Rumsey Taylor, and Miles Watkins. “An Extremely Detailed Map of the 2020 Election.” The New York Times, February 2, 2021, sec. The Upshot. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/upshot/2020-election-map.html.

Park, Andrea. “2020 Voter Turnout Was the Highest the U.S. Has Seen in Over a Century.” Marie Claire Magazine, November 5, 2020. https://www.marieclaire.com/politics/a34589422/voter-turnout-2020/.

Ballotpedia. “Presidential Election, 2020,” n.d. https://ballotpedia.org/Presidential_election,_2020.

Rowland, Robert. “The Rhetoric of Donald Trump.” University Press of Kansas, n.d. https://kansaspress.ku.edu/978-0-7006-3196-4.html.

Wood, Denis, and John Fels. The Power of Maps. Mappings. New York: Guilford Press, 1992.