By Scott T. Allison and George R. Goethals

As the year 2010 draws to a close, we take the opportunity to shine a spotlight on the year’s heroes. If you’ve been reading this blog or have read our book, then you know that we believe that heroism is in the eye of the beholder. Keep this in mind as you read the list below. These individuals are not necessarily our personal heroes; they are America’s heroes based on their actions, media coverage, Facebook following, and overall public interest. We constructed this list with assistance from Sean Ryan and Kyra Newman of the Hodges Partnership. In alphabetical order, the following individuals are America’s heroes for 2010:

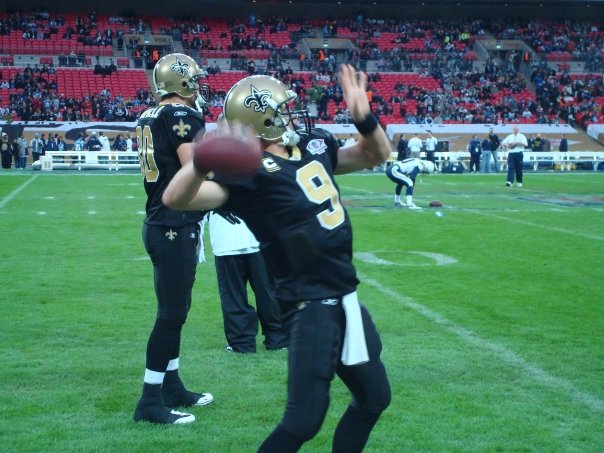

Drew Brees

Drew Brees

A career-threatening injury set long odds for Drew Brees ever leading an NFL team to the Super Bowl. Even longer were the odds of Brees leading the longtime-laughable New Orleans Saints to a Super Bowl title. Not only was Brees the cure for a losing culture in New Orleans, but he and the Saints also became the symbolic saviors of the hurricane-ravaged city. "Everyone loves the underdog, especially when that underdog has overcome such long odds to reach that pinnacle," Scott Allison said. "Drew Brees and the Saints became a symbol of hope, rebirth and inspiration for all of New Orleans and Americans alike."

Chilean Miners and Rescuers

For 70 days, the plight of the Chilean miners captivated the world. Almost as riveting was the teamwork of countless countries, who banded together to find a way to save the miners buried under a half-mile of rock. When the miners finally returned one-by-one to the surface, the world celebrated as one. "Inspiration is one of the key ingredients of a hero, and we all watched as these incredible men showed bravery, endurance, teamwork and courage," George Goethals said. "The entire affair epitomized what a hero is all about."

Armando Galarraga/Jim Joyce

Armando Galarraga/Jim Joyce

On an early June night, Detroit Tigers pitcher Armando Galarraga was perfect in the eyes of all but one man – umpire Jim Joyce. Galarraga's bid for a perfect game was denied when Joyce mistakenly called a batter safe at first on what should have been the game's final play. "Heroism was displayed almost immediately, as Galarraga barely argued the fact that one of the most precious prizes in sport was taken from him," Scott Allison said. "And afterward, Joyce faced the music, acknowledging his mistake rather than hiding behind a statement. His tears and sincerity and appearances on national TV were rare in today's society. As was Galarraga's sportsmanship throughout the whole ordeal, which isn't often seen in today's professional athlete."

Salvatore Giunta

In 2007, Salvatore Giunta's platoon was ambushed by enemy fire in eastern Afghanistan. Giunta ran into the firefight to pull a fellow soldier back to cover then fought off two insurgents who were carrying away another wounded American soldier. In November, President Obama presented Giunta with a Medal of Honor – the first time the nation's highest military award for valor has been given to a living service member since the Vietnam War. "To call Sal Giunta a hero would be an understatement," George Goethals said. "He represents the face of hundreds of thousands of men and women who have proudly served their country and is a true hero among heroes."

Lady Gaga

Lady Gaga

Immense talent €¦ check. Overwhelming popularity €¦ check. Promoting social change €¦ check. Lada Gaga fascinated fans all over the world with her pulsating music, intoxicating vocals and outlandish fashion. Equally noticed was her effort to support gay rights, particularly the plight of gays in the military. "The jury might still be out on Lady Gaga's long-term heroism," Scott Allison said. "But there's no denying the impact of her unique artistry on pop culture. There is something compelling about her courageous trailblazing in the areas of music, dance, fashion and redefining sex roles."

Liu Xiaobo

Sitting in a Chinese jail cell serving an 11-year sentence for subversion charges is Liu Xiaobo, the democracy activist who became the first Chinese to win the Nobel Peace Prize. Liu, a scholar, writer, poet and social commentator, long has been an advocate for political change and human rights. Of his selection for the Nobel Prize, the chairman of the award committee said, "It is a tragedy that a man is being imprisoned for 11 years merely because he expressed his opinion." "Courage and standing up for what you believe to be right is a fundamental of heroism," George Goethals said. "Mr. Liu, like Nelson Mandela and others before him, has not backed down from his beliefs, no matter the cost. He has empowered millions around the globe."

Michelle Obama

Michelle Obama

First ladies often are more popular than their husbands and parlay their clout into worthwhile causes. Obama moved beyond her image as a fashionista in 2010 to step into her very own bully pulpit. She launched the "Let's Move!" campaign to fight childhood obesity. Attacking the systemic problem on all fronts, her campaign knits together exercise plans, funding for neighborhood development, the promotion of fresh foods and farmers' markets movements, recipes from celebrity chefs and school cafeteria cooks. "First ladies draw attention, but they're not always heroic," Scott Allison said. "What makes Michelle Obama a hero is the simple fact that the American public can't get enough of her."

The Political Entertainers

Glenn Beck led the "Restoring Honor" rally. Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert produced the "Rally to Restore Sanity and/or Fear." And Bill O'Reilly, well, he was Bill O'Reilly, king of cable news show ratings. Combined, the voices struck a chord with millions of Americans. "No matter the side of the political fence, Americans were inspired by some of cable's talking heads," George Goethals said. "Because of the division in political opinion they personify, there's often a fine line that separates these heroes from being villains."

Steven Slater

You remember Mr. Slater, the JetBlue flight attendant who – allegedly irritated by a demanding passenger – gave new meaning to "I quit" when he screamed obscenities over the loudspeaker, grabbed a couple of beers and slid down the emergency chute. While many Americans simply shook their heads, millions celebrated Slater's exit strategy on countless Facebook fan pages and as a constant trending topic on Twitter. "Steven Slater is an example of what we call an €˜ephemeral' hero – a hero with a short shelf life," Scott Allison said. "Slater has become a folk hero to millions of Americans for acting out the fantasy of ‘take this job and shove it.'”

Betty White

Betty White

It all started with the Golden Girl playing pickup football and popping jokes in a Super Bowl ad for Snickers. Soon after, an Internet campaign persuaded "Saturday Night Live" to invite White to host in May. Not only was she the oldest person to ever host SNL, but she also helped the show deliver its highest ratings in a year and half and earned her seventh Emmy Award. Her amazing career resurgence of 2010 practically overshadowed her winning the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Screen Actors Guild. "Betty White proved that heroism can span generations," George Goethals said. "Who would have ever thought an 88-year-old would be one of the Internet sensations of the year? She has proven again to be an inspiration for millions, young and old alike."

– – – – – –

Do you have a hero that you would like us to profile? Please send your suggestions to Scott T. Allison (sallison@richmond.edu) or to George R. Goethals (ggoethal@richmond.edu).

Like this:

Like Loading...