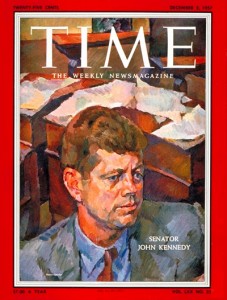

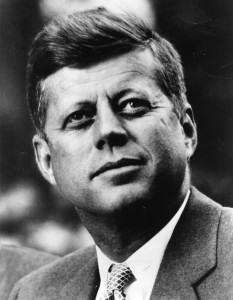

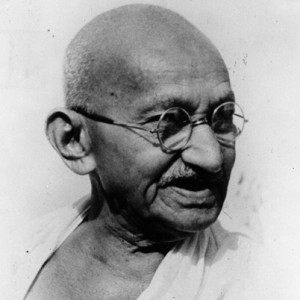

A great deal has been written and spoken about the 35th President of the United States, John F. Kennedy, who was assassinated over 50 years ago in November of 1963. While nobody who was sentient at the time is likely to misremember Kennedy’s assassination – or the funeral that followed it, or the killing of his assassin on national television – recollections of Kennedy’s presidency are not so pure. Human memory is imperfect in many ways. At best, it is selective. Much worse, memory is prey to numerous biases, errors and distortions.

In Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, Mark Antony said at Caesar’s funeral, “The evil that men do lives after them; the good is oft interred with their bones.” One wonders whether the opposite is true in Kennedy’s case. People are generally aware of both good and bad aspects of the Kennedy years, but memory of the good seems to win out. On the positive side are his charismatic persona, inspirational rhetoric and ambitious agendas. The negatives include philandering, passivity on some crucial issues and deception about his health. All of these and numerous other aspects of his administration are debated endlessly.

But there is one aspect of JFK’s presidency that has received too little attention. Kennedy felt that the Limited Test Ban Treaty with the Soviet Union, signed in August and ratified in September of 1963 outlawing nuclear tests in the atmosphere, was one of the most far-reaching accomplishments of his administration.  In a commencement address at American University in June of that summer, sometimes called the “Strategy of Peace” speech, Kennedy outlined the possibility of a completely new relationship with Russians, moving beyond the Cold War and its tensions and standoffs.

In a commencement address at American University in June of that summer, sometimes called the “Strategy of Peace” speech, Kennedy outlined the possibility of a completely new relationship with Russians, moving beyond the Cold War and its tensions and standoffs.

That speech and the test ban treaty were part of his evolving reexamination of super power relations. As a result, the word “détente” entered the American political vocabulary during the last weeks of the Kennedy administration, although it did not become widely used until the Nixon and Ford eras in the 1970s. Kennedy’s initiatives suggested what was possible for other willing presidents to achieve by way of reducing tensions with our Communist adversaries.

Kennedy had seen war himself and had seen men under his command die. He also had seen the United States and the Soviet Union come far too close to nuclear annihilation. He wanted very much to find ways to move beyond the Cold War and nuclear confrontation. His hard-line National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy once quipped to an aide that there were only two pacifists in the White House, “You and Kennedy.”

But Kennedy was no pacifist. He would have fully endorsed the Ronald Reagan/George H. W. Bush mantra that “peace through strength works.” But he was committed to building what would later be called a “new world order.” In his last months he consulted with Russian diplomats about joint ventures in space. He also came to believe that further American involvement in Viet Nam would never sustain the South Vietnamese regime. He announced the redeployment of 1,000 military advisers from that country.

Although the question is one of those persistent unknowns, it seems most probable that the full-scale American war in Viet Nam would  not have happened in a second Kennedy term. More generally, it seems safe to imagine that the world would have been very different had Kennedy not been assassinated. His intelligence and what psychologists call “openness,” that is, curiosity and broad interest in ideas and feelings, enabled him to grow and become ever more realistically flexible. These are personal qualities that almost always serve leaders well.

not have happened in a second Kennedy term. More generally, it seems safe to imagine that the world would have been very different had Kennedy not been assassinated. His intelligence and what psychologists call “openness,” that is, curiosity and broad interest in ideas and feelings, enabled him to grow and become ever more realistically flexible. These are personal qualities that almost always serve leaders well.

In the decade after Kennedy’s assassination, some held that within a generation JFK largely would be forgotten, remembered, if at all, as a young and promising president who served for a short time with mixed results. It was foreseen by few then that he would capture the country’s attention with unprecedented focus in the year 2013. But memory, both individual and collective, works in unpredictable ways.

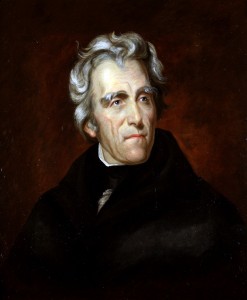

Images of Kennedy are pervasive and forever forged in our memories. We hear his voice, see him smile, listen to his banter with reporters and his speeches and comments on matters both large and small. After five decades, it may be time to organize our own recollections and what we have learned as we grasp an unforgettable American original.

We might start with remembering what he said at American University: “For in the final analysis, our most basic common link is that we all inhabit this small planet. We all breathe the same air. We all cherish our children’s future.”

– – – – – – – – – – – –

Dr. George R. Goethals holds the Robins Professorship in Leadership Studies at the University of Richmond’s Jepson School of Leadership Studies

The Soviet Union had won every gold medal since 1960 and the U.S. was a predictable flop during those years. Stunningly, the 1980 U.S. team defeated the Soviets to win the gold medal, but the Americans had been entrenched underdogs for so long that no one dared to suggest that their change in fortune was anything more than an aberration. The dismal U.S. performance at the subsequent Olympic hockey competitions confirmed their continued status as underdogs.

The Soviet Union had won every gold medal since 1960 and the U.S. was a predictable flop during those years. Stunningly, the 1980 U.S. team defeated the Soviets to win the gold medal, but the Americans had been entrenched underdogs for so long that no one dared to suggest that their change in fortune was anything more than an aberration. The dismal U.S. performance at the subsequent Olympic hockey competitions confirmed their continued status as underdogs. In a non-sporting business environment the Pirates’ survival prospects would be bleak indeed, but every year brings new hope for the lowly in athletics.

In a non-sporting business environment the Pirates’ survival prospects would be bleak indeed, but every year brings new hope for the lowly in athletics.