“If we never give up, and care enough for each other, we can do anything.”

-Hannah Taylor, 2006

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

By Kelsea Starr, Mike Rocco, & Rachel DeRosa

Often, the road to heroism begins with a powerful personal experience. Such was the case with inspirational Canadian teenager Hannah Taylor. As a 5-year-old, Hannah witnessed a homeless man eating from a garbage can in the cold of winter in Winnipeg, Canada. Deeply confused and saddened by this image, Hannah began inundating her mother with questions  about what she saw. She wanted to know how and why this could happen.

about what she saw. She wanted to know how and why this could happen.

With the clear-minded innocence of a 5-year-old, she asked her mother, “If everyone shared what they had, could that cure homelessness?” For about a year following this event, Hannah’s curiosity and sadness did not cease. She continued asking various family members about homelessness, a concept she simply could not begin to wrap her mind around.

One day Hannah’s mother suggested that perhaps Hannah should do something about this issue so that her “heart would not feel so sad.” The next day, Hannah approached her first grade teacher and asked if she could speak to her class about homelessness, what she had learned about the issue, and make possible suggestions for what they could do as a class to help. Hannah and her classmates proceeded to organize a bake sale and clothing drive from which proceeds would benefit local homeless shelters.

Upon seeing the success of this event, Hannah decided that her contributions would not stop there. In 2004, 8-year-old Hannah founded The Ladybug Foundation, a registered charity with the mission to end homelessness and alleviate the stigma associated with homeless people. She wanted others to understand that homeless people are not to be feared but are simply “great people wrapped in old clothes, with sad hearts.”

She selected the ladybug as her foundation’s mascot, as it is said to represent good luck. Hannah felt that good luck was not only crucial in her mission to help the homeless, but that this luck is also greatly needed by those in poverty. The foundation raises money to assist reputable charities throughout Canada which meet many of the needs of people who are homeless. As stated by 8-year-old Hannah at the time of the foundation’s creation, the goals of The Ladybug Foundation are as follows:

1. “To teach people that people who are homeless are just like you and me. They just need us to love them and care for them.”

2. “To teach everyone to treat people who are homeless like family because if you do that you will love them in all the right ways and care for them in all the right ways.”

3. “To teach people that no one should ever eat from a garbage can or live without a bed or a home and let them know that there are people that have to because they have no choice.”

4. “To ask every person that will listen to help however they can to make life for people who are homeless better.”

5. “To teach people that everyone can make a difference in the lives of others.”

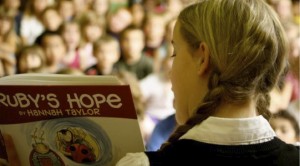

Since 2004, Hannah has spoken to over 175 schools and organizations. She has traveled throughout Canada, the U.S., Sweden, and Singapore, striving to educate the general public and bring dignity to the homeless population. She has also hosted a series of luncheons with various top business executives and community leaders across Canada to gain fundraising support. In 2007 Hannah published a children’s book called Ruby’s Hope, which further emphasizes the importance of helping those in need. Through her efforts, Hannah has raised over $2 million toward providing shelter, food, and safety for homeless people.

Hannah’s humanitarian efforts have not gone unnoticed. In 2007 she was awarded the Brick Award by the DoSomething! Foundation, which is presented to people under the age of 25 who have made a significant contribution to the lives of others. In that same year, Hannah also became the youngest person ever to receive Canada’s Top 100 Most Powerful Women Award. In honor of her great accomplishments, an emergency shelter has been named after her in Winnipeg, known as “Hannah’s Place.”

Hannah’s mission to help others continues to this day. She has founded a separate charity, called The Ladybug Foundation Education Program, implemented in various schools throughout Canada. This foundation provides resources to empower youth to discover what they are passionate about, get involved, and make a positive change.

Hannah’s story is inspiring and heroic, as it displays that with motivation and perseverance anyone can make a meaningful difference in the world, no matter how old you are. All you have to do care.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Kelsea Starr, Mike Rocco, & Rache DeRosa are undergraduate students at the University of Richmond. They wrote this essay as part of their course requirement while enrolled in Dr. Scott Allison’s Social Psychology class.

Like this:

Like Loading...

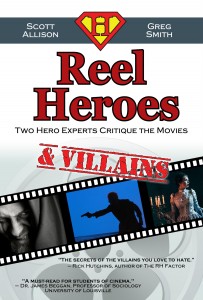

What makes a good movie hero? Which kinds of villains are the best — or the worst?

What makes a good movie hero? Which kinds of villains are the best — or the worst?