By Scott T. Allison

By Scott T. Allison

This blog post is excerpted from:

Goethals, G. R., & Allison, S. T. (2019). The Romance of heroism: Ambiguity, attribution, and apotheosis. West Yorkshire: Emerald.

Can anything be done to promote heroic transformation? Earlier we noted the pitfalls of being in charge of one’s own heroic growth. According to Rohr (2011b), engineering our own transformation by our own rules and by our own power “is by definition not transformation. If we try to change our ego with the help of our ego, we only have a better-disguised ego” (p. 5).

There are three things we can do, however, to make transformation more likely. From our review of theory and research on heroism, developmental processes, leadership, and spiritual growth, we can identify three broad categories of activities that encourage transformation. These activities include (1) participation in training and developmental programs,(2) spiritual practices, and (3) the hero’s journey. On the surface these activities appear dissimilar, yet these practices seem to produce similar transformative results.

1. Training and Development Practices

In examining the characteristics of people who risked their lives to save others, Kohen, Langdon, and Riches (2017) discovered several important commonalities. They found that these heroes “imagined situations where help was needed and considered how they would act; they had an expansive sense of empathy, not simply with those who might be considered ‘like them’ but also those who might be thought of as ‘other’ in some decisive respect; they regularly took action to help people, often in small ways; and they had some experience or skill that made them confident about undertaking the heroic action in question” (p. 1).

With this observation, Kohen et al. raise four points about preparation for heroism. First, they note the importance of imagining oneself as ready and capable of heroic action when it is needed. This imagination component involves the development of mental scripts for helping, an idea central to  Zimbardo’s Heroic Imagination Project (2018) hero training programs. Established a decade ago, the Heroic Imagination Project aims to encourage people to envision themselves as heroes and to “prepare heroes in training for everyday heroic action.” The group achieves this goal by training ordinary people to “master social and situational forces as well as their automatic human tendencies in order to act in ways that are kind, prosocial, and even heroic.” Participants are trained to improve their situational awareness, leadership skills, moral courage, and sense of efficacy in situations that require action to save or improve lives.

Zimbardo’s Heroic Imagination Project (2018) hero training programs. Established a decade ago, the Heroic Imagination Project aims to encourage people to envision themselves as heroes and to “prepare heroes in training for everyday heroic action.” The group achieves this goal by training ordinary people to “master social and situational forces as well as their automatic human tendencies in order to act in ways that are kind, prosocial, and even heroic.” Participants are trained to improve their situational awareness, leadership skills, moral courage, and sense of efficacy in situations that require action to save or improve lives.

Second, Kohen et al. (2017) emphasize the importance of empathy, observing that heroes show empathic concern for both similar and dissimilar others. A growing body of research supports the idea that empathy can be enhanced through training, an idea corroborated by the proliferation of empathy training programs around the world (Tenney, 2017). Svoboda (2013) even argues that empathy and compassion are muscles that can be strengthened with repeated use. Third, Kohen et al. note that heroes regularly take action to help people, often in small ways. Doing so may promote the self-perception that one has heroic attributes, thereby increasing one’s chances of intervening when a true emergency arises. Finally, Kohen et al. observe that heroes often have either formal or informal training in saving lives. These skills and experiences may be acquired from training for the military, law enforcement, or firefighting, or they may derive from emergency medical training, lifeguard training, and CPR classes (Svoboda, 2013).

In a similar vein, Kramer (2017) has devised a methodology for helping people develop the courage to pursue their most heroic dreams and aspirations in life. He identifies such courage as existential courage, consisting of people’s identity aspirations and strivings for their lives to feel meaningful and consequential. Kramer’s technique involves fostering people’s willingness to take psychological and social risks in the pursuit of desired but challenging future identities. His “identity lab” is a setting where students work individually and collaboratively to (1) identify and research their desired future identities, (2) develop an inventory or assessment of identity-relevant attributes that support the realization of those desired future identities, (3) design behavioral experiments to explore and further develop those self-selected identity attributes, and, finally, (4) consolidate their learnings from their experiments through reflection and assessment. Kramer’s results show that his participants feel significantly more “powerful,” “transformative,” “impactful,” and “effective” in pursuing their identity aspirations. They also report increased self-efficacy and resilience.

Another example of training practices can be found in initial rituals and rites of passages found in many cultures throughout the world. Although modern Western cultures have eliminated the majority of these practices, most cultures throughout history did deem it necessary to require adolescents, particularly boys, to undergo rituals that signaled their transformation into maturity and adulthood (Turner, 1966; van Gennep, 1909). In many African and Australian tribes, initiation requires initiates to experience pain, often involving circumcision or genital mutilation, and it is also not uncommon for rituals to include a challenging survival test in nature. These initiation tests are considered necessary for individuals to become full members of the tribe, allowing them participate in ceremonies or social rituals such as marriage. Initiations are often culminated with large elaborate ceremonies for adolescents to be recognized publicly as full-fledged adult members of their society.

initiation requires initiates to experience pain, often involving circumcision or genital mutilation, and it is also not uncommon for rituals to include a challenging survival test in nature. These initiation tests are considered necessary for individuals to become full members of the tribe, allowing them participate in ceremonies or social rituals such as marriage. Initiations are often culminated with large elaborate ceremonies for adolescents to be recognized publicly as full-fledged adult members of their society.

Child-rearing can serve as another type of transformative training practice. A striking example can be seen in Fagin-Jones’s (2017) research on how parents raised the rescuers of Jews during the Holocaust. Fagin-Jones found that the parenting practices of rescuers differed significantly from the parenting of passive bystanders. Rescuers reported having loving, supportive relationships with parents, whereas bystanders reported relationships with parents as cold, negative, and avoidant. More rescuers than bystanders recalled their parents as affectionate and engaged in praising, hugging, kissing, joking, and smiling. These early cohesive family bonds encouraged other-oriented relationships based on tolerance, inclusion, and openness. Rescuers reported that their family unit engendered traits of independence, potency, risk-taking, decisiveness, and tolerance. Bystanders, in contrast, recalled a lack of familial closeness that engendered impotence, indecisiveness, and passivity. Rescuers’ parents were less likely than bystanders’ parents to express negative Jewish stereotypes such as “dishonest,” “untrustworthy,” and “too powerful”. Overall, rescuers were raised to practice involvement in community, commitment to others’ welfare, and responsibility for the greater good. In contrast, bystanders’ parents assigned demonic qualities to Jews and promoted the idea that Jews deserved their fate.

2. Spiritual Practices

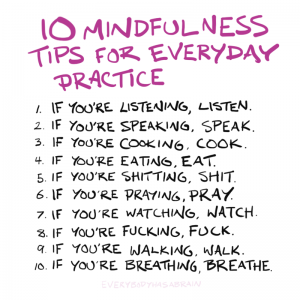

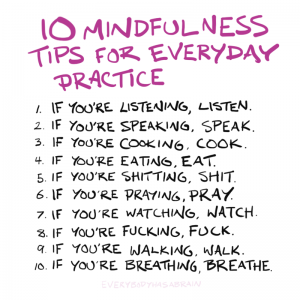

For several millennia, spiritual gurus have extolled the benefits of engaging in a variety of spiritual practices aimed at improving one’s mental and emotional states. Recent research findings in cognitive neuroscience and positive psychology are now beginning to corroborate these benefits. Mindfulness in particular has attracted widespread popularity as well as considerable research about its implications for mental health.  The key component of mindfulness as a mental state is its emphasis on focusing one’s awareness solely on the present moment. People who practice mindful meditation show significant decreases in stress, better coping skills, less depression, improved emotional regulation, and higher levels of resilience (Hofmann, Sawyer, Witt, & Oh, 2010). Mindful meditation quiets the mind and thus “wakes us up to what is happening,” allowing “contact with life” (Hanh, 1999, p. 81). Tolle (2005) argues that living in the present moment is a transformative experience avoided by most people because they habitually choose to clutter their minds with regrets about the past or fears about the future. He claims that “our entire life only happens in this moment. The present moment is life itself” (p. 99). Basking in the present moment is the basis of the psychological phenomenon of “flow” described by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (2008). When experiencing flow, people are “in the zone,” fully present, and completely “immersed in a feeling of energized focus” (p. 45).

The key component of mindfulness as a mental state is its emphasis on focusing one’s awareness solely on the present moment. People who practice mindful meditation show significant decreases in stress, better coping skills, less depression, improved emotional regulation, and higher levels of resilience (Hofmann, Sawyer, Witt, & Oh, 2010). Mindful meditation quiets the mind and thus “wakes us up to what is happening,” allowing “contact with life” (Hanh, 1999, p. 81). Tolle (2005) argues that living in the present moment is a transformative experience avoided by most people because they habitually choose to clutter their minds with regrets about the past or fears about the future. He claims that “our entire life only happens in this moment. The present moment is life itself” (p. 99). Basking in the present moment is the basis of the psychological phenomenon of “flow” described by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (2008). When experiencing flow, people are “in the zone,” fully present, and completely “immersed in a feeling of energized focus” (p. 45).

The spiritual attribute of humility can also be transformative. When asked to name four cardinal virtues, St. Bernard is reported to have answered: “Humility, humility, humility, and humility” (Kurtz & Ketcham, 1992). Humility has been shown to be linked to increased altruism, forgiveness, generosity, and self-control (Worthington & Allison, 2018). One can argue that humility cannot be practiced, as the idea of getting better at humility runs contrary to being humble. However, we suspect that one can practice humility by adopting the habit of admitting mistakes, acknowledging personal faults, avoiding bragging, and being generous in assigning credit to others.

Gratitude is another transformative spiritual practice validated by recent research. Algoe (2012) found that gratitude improves sleep, patience, depression, energy, optimism, and relationship quality. Practitioners have developed gratitude therapy as a way of helping clients become happier, more agreeable, more open, and less neurotic. Moreover, neuroscientists have found that gratitude is associated with activity in areas of the brain associated with morality, reward, and value judgment (Emmons & Stern, 2013). Closely related to gratitude are experiences with wonder and awe, which have been shown to increase generosity and a greater sense of connection with the world (Piff et al., 2015). Enjoying regular doses of wonder is a telltale trait of the self-actualized individual (Maslow, 1943).

Another transformative spiritual practice is forgiveness. Research shows that people who are able to forgive others have healthier relationships, improved mental health, less anxiety, stress and hostility, lower blood pressure, fewer symptoms of depression, and a stronger immune system (Worthington, 2013).  “Letting go” is another spiritual practice that can produce transformation. It has also been called release, acceptance, or surrender. Buddhist teach Thich Naht Hanh (1999) claims that “letting go give us freedom, and freedom is the only condition for happiness” (p. 78). William James (1902) also described the beneficial practice of letting go among religiously converted individuals: “Give up the feeling of responsibility, let go your hold, resign the care of your destiny to higher powers, be genuinely indifferent as to what becomes of it all, and you will find not only that you gain a perfect inward relief, but often also, in addition, the particular goods you sincerely thought you were renouncing” (p. 110).

“Letting go” is another spiritual practice that can produce transformation. It has also been called release, acceptance, or surrender. Buddhist teach Thich Naht Hanh (1999) claims that “letting go give us freedom, and freedom is the only condition for happiness” (p. 78). William James (1902) also described the beneficial practice of letting go among religiously converted individuals: “Give up the feeling of responsibility, let go your hold, resign the care of your destiny to higher powers, be genuinely indifferent as to what becomes of it all, and you will find not only that you gain a perfect inward relief, but often also, in addition, the particular goods you sincerely thought you were renouncing” (p. 110).

Finally, we turn to the complex emotion of love as a transformative agent. In addition to starring in Casablanca, Humphrey Bogart played the lead role in Sabrina, another film demonstrating the transformative power of love. In Sabrina, Bogart played the role of Linus, a workaholic CEO who has no time for love. His underachieving brother David begins a romance with a young woman named Sabrina, and it becomes clear that this budding relationship jeopardizes a multi-million-dollar deal that the company is about to consummate. To undermine the relationship, Linus pretends to show romantic interest in Sabrina, and he succeeds in winning her heart. Despite the pretense, Linus falls in love for the first time in his life, resigns as CEO, and runs away with Sabrina to Paris. Love has completely transformed him from a cold, greedy businessman into a warm, enlightened individual. Similar transformations in film and literature are seen in Ebenezer Scrooge (in A Christmas Carol), the Grinch (in How the Grinch Stole Christmas), Phil Connors (in Groundhog Day), and George Banks (in Mary Poppins).

In Man’s Search for Meaning, Viktor Frankl (1949) wrote, “The salvation of man is through love and in love” (p. 37). Thich Naht Hanh (1999), moreover,  weighs in that “love, compassion, joy, and equanimity are the very nature of an enlightened person” (p. 170). Loving kindness also transforms us biologically (Keltner, 2009). People who make kindness a habit have significantly lower levels of stress hormones such as cortisol. Making an effort to help others can lead to decreased levels of anxiety in individuals who normally avoid social situations. Being kind and even witnessing kindness have also been found to increase levels of oxytocin, a hormone associated with lower blood pressure, more sound sleep, and reduced cravings for drugs such as alcohol and cocaine. Loving others lights up the motivation and reward circuits of the limbic system in the brain (Esch & Stefano, 2011). Research also reveals that people who routinely show acts of love live longer compared to people who perform fewer loving actions (Vaillant, 2012).

weighs in that “love, compassion, joy, and equanimity are the very nature of an enlightened person” (p. 170). Loving kindness also transforms us biologically (Keltner, 2009). People who make kindness a habit have significantly lower levels of stress hormones such as cortisol. Making an effort to help others can lead to decreased levels of anxiety in individuals who normally avoid social situations. Being kind and even witnessing kindness have also been found to increase levels of oxytocin, a hormone associated with lower blood pressure, more sound sleep, and reduced cravings for drugs such as alcohol and cocaine. Loving others lights up the motivation and reward circuits of the limbic system in the brain (Esch & Stefano, 2011). Research also reveals that people who routinely show acts of love live longer compared to people who perform fewer loving actions (Vaillant, 2012).

3. The Hero’s Journey

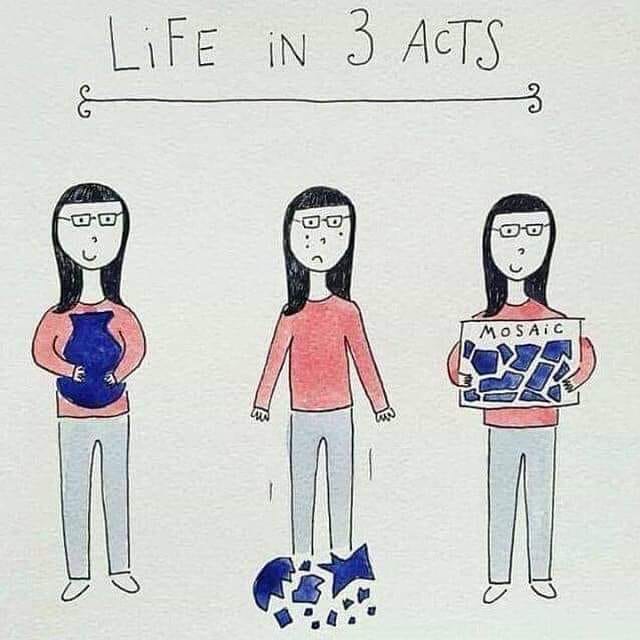

We opened this chapter by noting that the only way most of us undergo transformation is to embark on the hero’s journey. While we have complete control over whether we receive training that can facilitate a heroic metamorphosis, and over whether we engage in spiritual practices, we have far less control over our participation in the classic hero’s journey. We can only remain open and receptive to the ride that  awaits us. As we have noted, our departure on the journey can be jarring – we often experience an accident, illness, transgression, death, divorce, or disaster. The best we can do is fasten our seatbelts and trust that the darkness of our lot will eventually transform into lightness.

awaits us. As we have noted, our departure on the journey can be jarring – we often experience an accident, illness, transgression, death, divorce, or disaster. The best we can do is fasten our seatbelts and trust that the darkness of our lot will eventually transform into lightness.

But we cannot remain passive. During the journey we must be diligent in doing our part to secure allies and mentors, and to take actions that cultivate strengths such as resilience, courage, and resourcefulness (Williams, 2018). After being transformed ourselves, we feel the obligation to transform others in the role of mentor. Having traversed the heroic path, we may use our heroism to craft a newfound purpose for our existence, a purpose that drives us to spend our remaining years making a positive difference in people’s lives. Bronk and Riches (2017) call this process heroism-guided purpose.

– – – – – –

This blog post is excerpted from:

Goethals, G. R., & Allison, S. T. (2019). The Romance of heroism: Ambiguity, attribution, and apotheosis. West Yorkshire: Emerald.

Like this:

Like Loading...

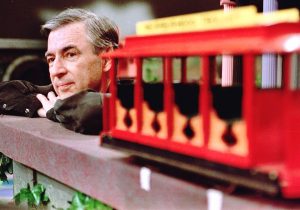

think of the people who have helped you become who you are. Ten seconds of silence.” Tears began to flow from the eyes of many in the audience. Rogers finally looked up from his watch and softly said, “Whomever you are thinking about, how pleased they must be to know the difference you feel they’ve made.” Actor LeVar Burton recalls a time when Rogers was invited to a gathering at the White House, and he asked everybody, including President Clinton, to close their eyes for 60 seconds and think about someone who had helped shape them. Again people wept. “Fred felt it was critical to acknowledge those who have helped us come into being,” said Burton. “And Fred’s legacy is that he is that person for so many of us.”

think of the people who have helped you become who you are. Ten seconds of silence.” Tears began to flow from the eyes of many in the audience. Rogers finally looked up from his watch and softly said, “Whomever you are thinking about, how pleased they must be to know the difference you feel they’ve made.” Actor LeVar Burton recalls a time when Rogers was invited to a gathering at the White House, and he asked everybody, including President Clinton, to close their eyes for 60 seconds and think about someone who had helped shape them. Again people wept. “Fred felt it was critical to acknowledge those who have helped us come into being,” said Burton. “And Fred’s legacy is that he is that person for so many of us.”