By Nick Inge

By Nick Inge

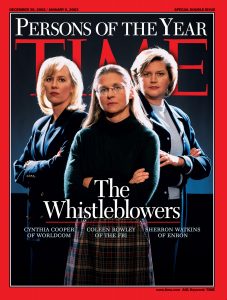

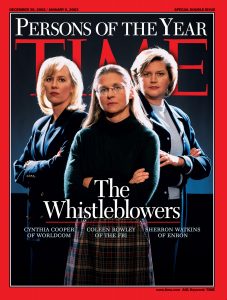

Who knows what it takes to tell the truth? The only people that really know are those that have done it and have spoken up — those that have spoken up about the wrongdoings of others. It takes a few to stand up for the many. Whistle-blowers do whatever it takes for them to reveal those who commit wrongdoing, for if they didn’t then the wrong-doing would continue. Unfortunately, in some cases, it has.

Whistle-blowers take the complicated and often very difficult decision to speak up whilst the vast majority of others, having wrestled with the decision, decide not to. Speaking up takes courage, tenacity and a clear sense of right and wrong to stand up for integrity in a world where it is easier to turn a blind eye. Whistle-blowers expose themselves to extreme scrutiny and invite forensic examination of their character and motivation.

Organisations that promote a healthy speak-up culture of openness and honesty not only improve the way they operate but develop a culture of trust and belief in all of their stakeholders. This culture has meant that those issues that have been highlighted by those who speak up have increasingly led to positive change in governments and in the behaviour of large corporations. They have exposed the unlawful behaviour of high-profile individuals in the fields of commerce, entertainment, politics and sport.

fields of commerce, entertainment, politics and sport.

However, the vast majority of whistle-blowers have concerns relating to their work and their surroundings. For many the concept of whistle-blowing may sound daunting, terrifying, disloyal and for some, difficult to accept. It puts many people in a position that makes them feel extremely vulnerable. Vulnerable to losing their livelihoods and all that entails. They go through a rollercoaster of emotions and many challenging situations.

Whistle-blowers are those of us that possess dignity, respect and a sense of doing something rather than nothing. Whistleblowing at any level is not for the faint-hearted. It takes courage, resolve, passion, belief, faith and perseverance. It involves using every ounce of one’s integrity as well as a great deal of support from friends and family to do the right thing. This is dependent on someone’s morals, ethics, age, support network, and experience. Providing information about bullying, harassment, corrupt practices, poor leadership and back-handers takes a lot of backbone.

Whistle-blowers are brave. It takes guts and a fundamental belief in justice to stand up and be counted. To see right prevail over wrong. Those who blatantly flout the rules and think they can get away with it, because of their position, need to be held accountable. There are those that make the system work for themselves at the expense of others and this is what drives people to speak up. It takes resolve and perseverance. It takes an unwielding belief by those that report wrongdoing that they are 100% correct in what they witness.

‘It takes the few to stand up for the many’

This article highlights the issues that people face when confronted with the dilemma of whether to speak up or not, what then motivates them to do so, the personality traits of those that do and the lessons that we can learn from them, both from an individual perspective as well as from society as a whole.

The Difficulties Facing Potential Whistle-Blowers

How does it feel to speak up and how do people do it? Do they mainly do it overtly or covertly? That’s to say do they do it not worrying about being in the spotlight or do they do it, for example, via an anonymous hotline? If they do it this way what would happen if they were identified? How do people feel if they are labelled as a ‘grass’ or a ‘snitch’? What is it like to be labelled as someone who cannot be trusted with a secret?

When is the exact time and moment that people tell someone what they know? Will they be believed and will they be taken seriously? Would whoever speaks up become paranoid?  Will they be ready for any backlash from friends, colleagues and potentially their employer? How will they cope and what will be the long-term effects?

Will they be ready for any backlash from friends, colleagues and potentially their employer? How will they cope and what will be the long-term effects?

Below are a few emotions that people who speak up experience and questions which they may want answers to. The following ones are those highlighted as being the feelings that they are most likely to experience:

Isolation

Telling the truth to someone about another person may make them feel terribly isolated, disloyal, angry, in despair and vulnerable.

Why Me?

People may wonder how they ever found themselves in that position. Those that speak up at work probably complied with all the policies and procedures that were put in place to protect them but they find themselves in a position that they had no other option other than to speak up. It may feel to them like they are on the outside of the situation looking in on someone else’s. It can be a strange place being caught up in the middle of a situation which they cannot control other than to ‘do the right thing’ and then make a disclosure. It is normally an invidious position to be in.

Disapproval

People may approve, disapprove, support or not support those that speak up. Those that speak up may find that they themselves have an adverse effect on their family as well as their friends. They may think that they are going mad. It can be an extremely stressful time of any-one’s life and one which they would not envisage or want themselves to be in. It is nothing that anyone can really prepare for. Those that speak up may need counselling in the very early stages of the process of having made a disclosure to help them come to terms with what they have done. They should not be afraid or embarrassed to take it.

Paranoia

Those that speak up may feel paranoid – are those that they reported on watching them? What will be the consequences of telling the truth? Will there be any backlash? It is a time when in my experience people wonder whether the organisation that they have made a disclosure about is out to get them.

Escape

It may feel easier for people who speak up just to run away but this is not likely to be possible. People have careers, families and financial commitments amongst other things and it really is not feasible for people to disappear and wait for the dust to settle.

Sleeplessness

They may wake up in the night because they cannot get the situation out of their head. This is a common issue that is faced by those who have yet to speak up and have got to do so. Medication may be the answer for some.

Obsessive Thoughts

They may be constantly thinking about conversations and scenarios (past, present and future). The stress of the situation is relived in people’s minds and it goes round and round in their heads.

Information

Whistle-blowers may obtain snippets of information from friends and colleagues which allow them to piece together their next move. The state of high alert that people find themselves in ensures that they hang onto every word that may be of relevance to the disclosure that they have made.

All the good qualities that they may have had as a person may well disappear as they want those that they have reported on to admit the truth (which they may) and, if they do not, suffer the full consequences. They may wonder  whether other colleagues who may have witnessed wrongdoing stand by them. It may be that whatever they say initially in support of the whistle-blower may evaporate as time passes and the wrongdoers curry favour with those left behind.

whether other colleagues who may have witnessed wrongdoing stand by them. It may be that whatever they say initially in support of the whistle-blower may evaporate as time passes and the wrongdoers curry favour with those left behind.

One of the major problems that people will encounter when faced with the dilemma of what to do concerns who to tell. Do they tell their friends, family, the wrongdoer, colleagues, or even an anonymous whistleblowing hotline or app? Would they perhaps use the media? The first person that they are likely to tell is their partner or a very close and trusted friend. This person may have nothing to do with their work but are someone for them to offload on. Someone that they can trust who will listen and who will be sympathetic – someone to give them advice.

‘There is another way. The right way’

One of the questions that any would-be whistle-blower might ask themselves – is it worth all the angst and worry compared with their anger and sense of justice should any enquiry prove to be unsuccessful and those that commit the wrongdoing go unpunished? This could be weighed up against the maximum punishment that could be brought against a wrongdoer and a sense of justice be found, ie. will it all be worth it?

My advice to anyone who is thinking about speaking up is know everything about what the process is before embarking on a whistle-blowing journey. What would they want out of it? They have to ask themselves what will realistically happen. Will they be happy with the outcome of an investigation or is it simply enough to know that they have done their bit? They should also make sure that what they do is valid, ie. is it in line with the organisation’s speak-up policy? It may well lead to them questioning their morals, their principles and values, their sanity and their religious beliefs.

With all these questions in people’s minds they may be thinking – what is the point? Nothing appears clear and there is no apparent right or wrong way of getting through the journey. My advice to them is this – look at yourself as a human being. If you can say with 100% certainty that you know what others have done is wrong and regardless of the outcome, you can leave this planet knowing that you were honourable, true to your word and courageous,  then do it. Do not do it solely for the benefit of others. Do it so that you can look the wrongdoer in the eye and know that you are right and they are wrong. Once they have determined that they are in that place then making a disclosure will be an inevitability.

then do it. Do not do it solely for the benefit of others. Do it so that you can look the wrongdoer in the eye and know that you are right and they are wrong. Once they have determined that they are in that place then making a disclosure will be an inevitability.

To make this happen and see it through to the end they need an appetite: a massive appetite. A desire to let someone know what has happened and then stay the course. Whistle-blowers need a positive outlook, a motivation to ensure that the full facts emerge and the stamina to see it through to the end.

Desire

Desire is half the battle. If you think you can, you can. If you think you cannot, you will not. Whistle-blowers need to believe in their own ability to do what they know in their heart is right and indeed that hunger has to come from deep in their soul. Only they know how hungry they are for the truth to be revealed. Only they know what this will mean for other people. They have to put themselves in their shoes. How hungry would they be for someone to have the courage to speak up on their behalf.

Determination

The determination to reveal the truth doesn’t just come from those who speak up. There are others who do not even know about the wrongdoing but will give the whistle-blower added determination once they have revealed any wrongdoing. So they have to do not do it just for them but do it for others who have been directly affected as well as for a wider group of people who will want them to do this in the interests of morality, ethics, and justice. No-one wants to see those committing wrongdoing get away with it. Whistle-blowers have to be the one who stands up and who are counted.

Do the Right Thing

How many times throughout history have we seen the domino effect where something begun by just one person turns into an avalanche of claims that uncover wrongdoing on a massive scale. Mark Felt (Richard Nixon), and more recently Christopher Wylie (Facebook/Cambridge Analytica), are examples of how just one person can change the course of history for the better. Without these people the world would have been none the wiser and further cheating, wrongdoing and deceit would have been carried out. Without whistle-blowers there would be unknown continuing victims of sexual abuse, bullying, human trafficking, or breaches of data protection on an industrial scale – and those people would still be suffering.

What motivates them

Why on earth would you want to provide information as a whistle-blower? What would impel you to speak up and provide information about others? The list of reasons as to why people provide information is infinitely long and highly personal to each and every person who does so. They are unique reasons based on that individual’s experience, age, situation, and knowledge.

What have you done recently that you are proud of? Is it helping out a neighbour or guiding an elderly person across the road? It may be something different. Could you help a colleague who is being bullied at work by identifying and providing evidence against the bully to ensure your colleague no longer suffers?  Could it be that, by revealing the truth, in years to come someone you helped at work with whom you are no longer in contact thinks of you and thanks you for your selfless act?

Could it be that, by revealing the truth, in years to come someone you helped at work with whom you are no longer in contact thinks of you and thanks you for your selfless act?

The important fact is that those who speak up are motivated to stand up and be counted, instead of looking the other way and not doing anything. It is easy to do nothing, far more difficult to say something. The act of doing good with regard to whistleblowing is not an easy one and is something the vast majority of people would not do. It is generally carried out as a one-off act of bravery. Due to its very nature there are no professional whistle-blowers! Therefore those who decide to speak-up are part of a very small exclusive club. They can have an amazing feeling that they have changed someone’s life by being brave.

‘See evil, feel evil, hear evil. Do something about it’

Listed below are the main reasons that drive people to provide information about others, both in a criminal and in a civil context:

Moral

Everyone knows the difference between right and wrong. The vast majority of people know when something is right and when it is not. And everyone knows on a sliding scale where the boundaries are crossed. For example, if you are a passenger travelling in your boss’s car, you would be very unlikely to report them for speeding if they went 5km/h over the limit; however, if they drove at 100km/h an hour that would probably be a completely different situation. Your reaction will depend on your relationship with that person, your position in the company, your age and experience, and your background (have you just had a speeding ticket?). The moral maze is very complicated one and hazardous to navigate.

Dislike

I know very few people in life who go through their working week without disliking someone. I’m not just talking about a mild dislike, I’m talking about a complete disdain for another human being; someone you dislike because they’ve not been nice to you and whose every action irritates you. It might be someone who you have had to be nice to for a very long time, who keeps getting away with things, knows how to “play the game” and about whom you know that, but for a small amount of digging, someone could find the truth and teach that person a lesson.

‘There is a big difference between knowing the truth and telling it’

Religion

You may not be religious in any way. My religion involves having a good heart and faith in humanity. There are good and bad people in every organisation. Having faith is your faith. Believe in what you believe. If your religion tells you that certain things are right or wrong, then that is fine as long as what you believe does not conflict with the law and the policy of your organisation. If this is the case, revealing wrongdoing becomes easier because of your faith. You may benefit from having someone in your faith that you trust and can turn to for advice, and this can be of great value to you. Whistle-blowers can find faith in religion and this may be one of their motivating factors.

Excitement

Some of those that I have met have honestly got such a kick out of passing on a secret. There is a particular thrill involved in knowing a secret and then telling it to someone. We have all had conversations where a friend says to you …“Psst. Do not tell anyone that bla bla bla”. You then reply, “I promise, I really promise”. Then you meet someone that would like to know what you have to say – you say to them, “Psst. Do not tell anyone. Promise not to tell anyone. I mean promise. Really promise”. You then tell all. How do you know that that person is not going to go and tell someone else? You hope they do not. How will you feel if they tell someone in the same way you did? The secret you have may be very difficult to keep. You want to tell everyone and the excitement when you do, mixed with all the other emotions, will be part of this process.

Loyalty

Loyalty develops slowly over time. It depends on age, experience, trust, rewards, and family. It has to be based on real actions, not phony ones. This is what motivates some that speak up.

Revenge

Revenge is sweet. It involves getting back at someone who has done you a disservice, or someone or something that has upset you. You do not need any other reason to blow the whistle. You just want the person to know they have been found out and there can be no better reason than that. Whatever you do, always tell the truth and no more. Those that speak up should not embellish the truth to suit their needs as it will come back and bite them. However, tempted they are to tell more than they actually know, just seeing the wrongdoer caught out or undone by their own actions should be satisfaction enough.

Jealousy

Although not a common reason to speak up, it is common enough to feature here. It might be that those who work for an organisation find that nepotism and the old boy network have got to them over the years. They may have been passed over for promotion, side-lined for political reasons, or there has been a complete disregard for their loyalty and service to the organisation, along with very little recognition of the hard work that they have put in. This be their chance to tell the truth and see that person receive some justice. It may well be that they have reached a tipping point on their ‘axis of anger’ and that they have seen someone promoted to a point where they think enough is enough.

Money

Some say this is not the main driver. However, this is nonsense. Wave cold, hard cash in front of people and they will talk. Money matters and money talks. Even if someone initially says they do not want money in return for information, in the vast majority of cases, they will take it if offered. To some people it is their main driver, to others it helps them through the month. Some may even give it to charitable cause.

When offered money, the majority of people find it hard to turn down. Information is very difficult to put a price on – how do you value it? This may depend on the amount, the quality, the nature of the situation, and the risk the whistle-blower took to obtain it? Its value is very subjective. To someone who has nothing, any amount may be seen as huge – to a wealthy businessman, it could be seen as insulting. It is a difficult call to make and few people want to be insulted.

In the criminal world, whistle-blowers pay no tax or national insurance. If you had little income and received a large monetary reward, how would you account for this? How could you spend it safely without friends becoming suspicious? How could you store it safely? The management of reward money is a major factor in keeping whistle-blowers safe and rigorous safeguards are put in place to ensure accountability.

On most occasions, whistle-blowers will have their expenses paid, such as the cost of getting to the venue, telephone calls, perhaps a drink or food when meeting their handler. Large amounts of money are generally paid in stages to avoid suspicion from friends and family as to how they obtained such large payments without seemingly working for them. Large amounts must therefore be risk-assessed so that the whistle-blower is not exposed by having to account for them. Small amounts have to be carefully managed so that, for example, drug users do not potentially overdose on the money they have been given. Oh, if money was simple to manage – the root of all evil and good!

The correct use of money is invaluable in terms of gaining outstanding intelligence. You cannot obtain an insight into the activity of those you are interested in by not paying decent amounts of money.

The vast majority of people have a price. What would yours be? £5, £10, £100, or £1000? Would you exchange information in return for money? What information do you have that someone else would pay money for? Could you accept ‘blue money’? Would it be a step too far? In my experience very few whistle-blowers refuse money – the majority take it. In any case, who cares? As a covert whistle-blower you do not have to tell anyone.

Is money really the root of all evil? Think of the good a well-placed whistle-blower can do. For example, they could:

- Recover stolen property that is of sentimental value to the owner.

- Arrest someone who has committed a crime.

- Reveal a crime.

- Provide insight into the minds of those who wish to do harm.

How can this be measured? Is it worse to be the informant or the authorities? What you know could be the last, vital piece of information in the intelligence jigsaw. It is all highly subjective, but intrinsically you have to be fair, honest, subject to scrutiny, and full of integrity. The list goes on.

Money is a way of saying thank you. Thank you for your time, thank you for your effort, and thank you for your information. I have never heard someone who manages a whistle-blower say that they have paid too much to someone. If anything, it is normally not enough. The risk people take to pass information on and regularly meet their handler should not be underestimated. The risk of compromise is very real and places whistle-blowers under considerable stress.  To be paid small amounts of money on a regular basis – £50, £100 or £150 – is, in my opinion, not worth the gamble. To entrust the authorities with your life is unlikely to be seen as worth the risk. Very few informants I have met have been genuinely satisfied with what they have been given. Everyone always wants more. Authority budgets have been reducing, leading to increased pressure being placed on formal budgets to provide more value for money.

To be paid small amounts of money on a regular basis – £50, £100 or £150 – is, in my opinion, not worth the gamble. To entrust the authorities with your life is unlikely to be seen as worth the risk. Very few informants I have met have been genuinely satisfied with what they have been given. Everyone always wants more. Authority budgets have been reducing, leading to increased pressure being placed on formal budgets to provide more value for money.

Whistle-blowers will generally never become rich by providing information. The money will help get the car serviced, buy a nice meal, and generally help out with household bills. It is a gesture, no more than that. It is true that some whistle-blowers are given large sums that can make a massive difference, but this is not a common occurrence. Obviously, the more the risk the higher the value of the commodity, and the time saved by the authority is always in favour of the amount paid. The figure is always a round one and never paid until the very last moment. This is for ease of payment and shows that paying for information is not an exact science.

I have known whistle-blowers to be paid considerable amounts that may appear excessive to the public. I can understand the sentiment but, balanced against the time saved trying to catch increasingly sophisticated criminals, I believe this is money well spent. In comparison with not catching people, or even when the authorities are trying to catch people, the rewards paid in relation to the cost to the taxpayer are very small. The press periodically publicise the amount spent on informants, but do not set this against the overall cost of covert policing – a legitimate tactic – and, when used properly, how cost-effective this method of intelligence gathering can be.

‘The challenge is doing the right thing. To ignore is doing the wrong thing’

Having dealt with literally hundreds of whistle-blowers over nearly twenty years I have witnessed similarities in the character of all those who have spoken up. They may have differed massively in their personalities and motivations but those that speak up are in the main strong, humble and determined to do the right thing. Those that provide information over a protracted period of time remain patient and resolute. They are principled, steadfast in their belief that they are right and all take a leap of faith when they decide to speak up. They normally reach an age with a certain amount of experience and life skills when they decide that morally they cannot keep quiet any longer. They normally have a deep sense of justice and are tenacious.

To speak up is not for the fainthearted. They have a sense of intolerance to wrongdoing and a strong sense of self belief in what they disclose is right. They are generally outraged by what they have witnessed and are brave individuals as they know that, if they do it anonymously and should they be identified, then they could suffer repercussions for both their career and personal life.

There are many lessons that can be learnt from those that decide that enough is enough who decide to speak up. In order to help quantify the issues that people face when deciding to speak up I conducted a short survey (Survey Monkey, May 2020). This was based on a sample of 40 people:

- Would you speak up if you knew about something that was wrong at work? Yes 95%; 5% No

- Have you ever spoken up? Yes 85%; 15% No

- Do you think your organisation takes speaking up seriously? Yes 55%; 45% No

- Do you think that your position within an organisation matters when deciding whether you would speak up or not? Yes 55%; No 45%

- Do you think that people are nowadays more likely to speak up at work if they witness wrongdoing they would have done in the past? Yes 70%’ 30% No

These figures somewhat surprised me. It appears that the vast majority of people have spoken up despite the fact that they don’t believe that the organisation takes speaking up seriously. This then begs the question why do people do it? In my experience the vast majority do it because of the attributes that I have outlined above. A strong sense of right and wrong and an understanding that the person who makes the disclosure will not be able to act as judge and jury, should any investigation result in a ‘guilty’ verdict for those that have committed wrongdoing.

Concluding Thoughts

There are many issues that whistle-blowers face in the 21st century. These haven’t fundamentally changed since people have started telling the truth. People have never wanted to be seen as snitches, grasses or snouts. Holding such a title is not one that attracts many suitors. It carries with it a certain stigma.

Those that speak up worry about being ostracized by their colleagues, losing their career and all that entails. It has never been recommended as a great career move. But the world has fundamentally changed. Certainly, since the outbreak of COVID-19 people have become frustrated with the ‘system’. They realise that by speaking up the world can be changed by people taking a stance against wrongdoing in whatever form it is found.

In the UK speaking up has recently brought to the fore issues such as BLM and lack of PPE in the NHS. Organisations are starting to realise that values that customers and clients hold true are openness, honesty and integrity; that this starts with them feeling empowered as employees; that they both need a voice and have one, too. Social media has enabled those who feel that they have previously not been able to speak up can now do so virtually anonymously via social media platforms.

Organisations that do not allow their staff to speak up run the risk that their employees will speak up outside of their workplace. This may explain why the vast majority of people have stated that they have spoken up and by doing they have done the right thing. It is therefore of concern that the majority of those that took place in the survey did not feel that their organisation took speaking up seriously. That the organisation allowed them to speak up but then didn’t do much about it. That staff feel empowered to speak up but by doing so it became a futile act. That their heroism by speaking up was in fact a worthless exercise. That the characteristics that they display, that the motivation that they have to try and rid their organisation of wrongdoing and that the sense of right and wrong that they feel deep in their fabric is just paid lip service to by their employer.

It therefore follows that speaking up just then becomes a tick box exercise for the organisation. That the whistle-blower finds it within themself to speak up and the organisation appears to have a speak up culture. The heroism of whistle-blowers, with all that entails, should not be devalued by this modern way of some organisations interpreting their own version of a speak up culture.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

After graduating with a BA (Hons) Economics in 1994, Nick Inge joined the UK Police. He soon started recruiting and handling informants, specialising in serious crime, counter-terrorism and corruption. Nick retired from the police in June 2019. Nick is now the CEO of a specialist whistleblowing consultancy, iTrust Assurance Ltd and the Co-founder of a social enterprise Worldly Wise. Nick is also a volunteer Careers and Enterprise Adviser for The Careers and Enterprise Company and the author of two books.

After graduating with a BA (Hons) Economics in 1994, Nick Inge joined the UK Police. He soon started recruiting and handling informants, specialising in serious crime, counter-terrorism and corruption. Nick retired from the police in June 2019. Nick is now the CEO of a specialist whistleblowing consultancy, iTrust Assurance Ltd and the Co-founder of a social enterprise Worldly Wise. Nick is also a volunteer Careers and Enterprise Adviser for The Careers and Enterprise Company and the author of two books.

Nick’s first book on whistleblowing can be found here, and his second book can be found here.

Like this:

Like Loading...

The journalist James Fallows and his wife Deborah have spent years visiting these functioning communities and reporting the civic engagement that has transformed regions, cities, and even neighborhoods that spark the kind of positive civic activity that eludes our national leadership. The Fallows have collected the stories of several of these community transformations in a book called Our Towns.

The journalist James Fallows and his wife Deborah have spent years visiting these functioning communities and reporting the civic engagement that has transformed regions, cities, and even neighborhoods that spark the kind of positive civic activity that eludes our national leadership. The Fallows have collected the stories of several of these community transformations in a book called Our Towns.

art, music, writing and other expressive arts. In time, the city of Greenville donated an 8 acre landscaped campus and $27 million in seed money. The school opened full time to high school juniors and seniors in 1999

art, music, writing and other expressive arts. In time, the city of Greenville donated an 8 acre landscaped campus and $27 million in seed money. The school opened full time to high school juniors and seniors in 1999 neighborhoods. And as word got out applications spiked. Once parents learned about “The Gov” interest became so strong that the local Lowe’s home store offered discounts on camping gear for parents who camped out on the campus waiting for a chance to place their kids on the wait list.

neighborhoods. And as word got out applications spiked. Once parents learned about “The Gov” interest became so strong that the local Lowe’s home store offered discounts on camping gear for parents who camped out on the campus waiting for a chance to place their kids on the wait list. In the words of Mr. Higgins, a born and bred southerner, “Eurocopter was a really big deal. In a county and state where most people think that women are all barefoot and pregnant—and we’re all members of the Klan—we’re now making shit that flies!!”

In the words of Mr. Higgins, a born and bred southerner, “Eurocopter was a really big deal. In a county and state where most people think that women are all barefoot and pregnant—and we’re all members of the Klan—we’re now making shit that flies!!”

By Scott T. Allison and George R. Goethals

By Scott T. Allison and George R. Goethals