An online conversation with my dear friends Olivia Efthimiou, Ellie Jacques, and Sylvia Gray, got me thinking about whether we can choose to become a hero and how much fate, luck, or circumstances — forces beyond our control — just make heroism happen.

It’s an issue about heroism that is both psychological and philosophical. Can we receive heroism training and do what it takes to transform ourselves into heroes? Or is heroism something that is “done unto us”?

Way back in 1966, a highly underrated psychologist named Leslie Farber noted that most of the best psychological states that we strive for cannot be “willed” by us. These are things like happiness, wisdom, courage, resilience, and even a good night’s sleep. For example, I can decide to read books but I can’t decide to be wise. I can do fun activities but I can’t “will” happiness. I can go to bed at 11pm but I can’t “will” myself to sleep.

I would say the same is true for transforming ourselves into heroes. We can do things to make heroic transformation more likely, such as attend Hero Round Table conferences, participate in hero training, or engage in mindful meditation — in much the same way we can make sleep more likely by going to bed.

But like falling asleep, we can’t “will” heroism.

Last year, Thai Navy Seals risked their lives to save a group of soccer boys trapped in a cave. These Navy Seals didn’t become life-saving heroes until circumstances presented themselves that  allowed for heroism to happen. Those Seals had the training and were ready, for sure. But most Seals don’t save a soccer team. (And we should be thankful that most training goes to waste — imagine the bloody carnage of a world where every trained hero uses their training)

allowed for heroism to happen. Those Seals had the training and were ready, for sure. But most Seals don’t save a soccer team. (And we should be thankful that most training goes to waste — imagine the bloody carnage of a world where every trained hero uses their training)

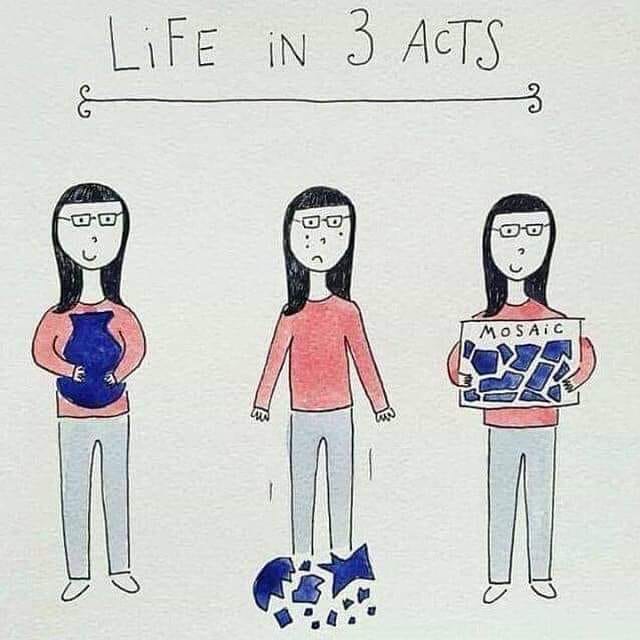

In short, there are some “end states” that we cannot “will” to happen – they have to happen as byproducts of various behaviors, experiences, and processes, some of which we can control and some we cannot.

One of my favorite quotes was penned by Georges Bataille: “Mere words have something of a quicksand about them. Only experience is the rope that is thrown to us.”

We cannot vow to become courageous and resilient — we have to go through tough times to acquire courage and resilience. Experience is the rope thrown to us — and we must grab that rope even if, and maybe especially if, the experience is painful.

By the way, Farber says that we live in a society that confuses these “two realms of will”, resulting in rampant anxiety and depression in people who try hard to make wonderful things happen that cannot happen when we want them to. So think twice before making either happiness or heroism your goal.

The hero’s journey “happens” to us; it’s not something that we plan. In fact, if we were in charge of the planning, we’d try to avoid the painful journey altogether! The ego cannot be in charge of our destiny. We have to wait for heroism to happen, and sometimes it never will. Which is okay.

Yes, we can decide to do things that make heroic growth more likely. These things include taking CPR classes, getting EMT training, engaging in spiritual practices, and enrolling in hero training programs. But let’s be honest — participating in these activities does not guarantee that you will become a hero.

Remember, experience is the rope thrown to us. Get out there and experience life. Don’t sit at home waiting for meaning and purpose to just “happen”. Do things, go places, and risk being uncomfortable.

Perhaps the title of this essay shouldn’t be, “Can You Try to Become a Hero, or Does it Just Happen to You?” Rather, the truth may be closer to, “You Can Try to Become a Hero, and it Might Just Happen to You.” You can’t plan for it, but you can prepare for it.

Knowing all this, I’m doing all I can to prepare for heroism, whether it happens or not. And so should you.

By Scott T. Allison

By Scott T. Allison lovable coward whom everyone dismisses but he evolves into a brave and stalwart member of the night’s watch. Daenerys Targaryen is, at the outset of Game of Thrones, mere breeding stock for the Dothrakis yet she emerges as the most powerful ruler of the seven kingdoms.

lovable coward whom everyone dismisses but he evolves into a brave and stalwart member of the night’s watch. Daenerys Targaryen is, at the outset of Game of Thrones, mere breeding stock for the Dothrakis yet she emerges as the most powerful ruler of the seven kingdoms. 4. Heroic Transformation. During their journeys, heroes undergo significant

4. Heroic Transformation. During their journeys, heroes undergo significant