By Scott T. Allison and George R. Goethals

By Scott T. Allison and George R. Goethals

In our research on the subject of heroism, we’ve been surprised at times about the ways in which people choose and maintain their heroes. Here we present these surprises to you in the form of seven paradoxes. Maybe these paradoxes don’t strike you as surprising at all, but to us they reveal an unexpected psychological richness about the hero concept.

Paradox 1: The truest heroes are fictional heroes. When we’ve asked people to list their heroes, a third of the heroes listed were the products of someone else’s imagination. In fact, many people listed only fictional characters as their heroes. When we asked one respondent to explain why he listed only fictional heroes, his reply was very revealing: “The only real heroes are fictional heroes.” This mindset prompted us to conduct a study in which participants were asked to rate the overall “goodness” of a group of randomly selected heroes and villains. We found that fictional heroes and villains were rated as more definitely good or bad than their real-world counterparts. Fictional heroes are indeed “truer” heroes.

Paradox 2: We all agree what a hero is, but we disagree who heroes are. Our research has shown that most people agree that heroes are supremely moral, supremely competent, or both. But people rarely share the same heroes.  Thus people who agree about the definition of heroes often vehemently disagree about specific choices of heroes. A telling example occurred when a colleague of ours loved our definition of heroes, agreed with our philosophy that “heroism is in the eye of the beholder”, but then fervently questioned our decision to include actress Meryl Streep as an example of a hero. It didn’t matter that we pointed to the fact that some of our survey respondents listed Streep as their hero. What was most important to our colleague was that Streep simply didn’t appear on her own personal list of hero exemplars.

Thus people who agree about the definition of heroes often vehemently disagree about specific choices of heroes. A telling example occurred when a colleague of ours loved our definition of heroes, agreed with our philosophy that “heroism is in the eye of the beholder”, but then fervently questioned our decision to include actress Meryl Streep as an example of a hero. It didn’t matter that we pointed to the fact that some of our survey respondents listed Streep as their hero. What was most important to our colleague was that Streep simply didn’t appear on her own personal list of hero exemplars.

Paradox 3: The most abundant heroes are also the most invisible. An important type of hero is called the Transparent Hero, who does his or her heroic work behind the scenes, outside the public spotlight. Transparent heroes include teachers, coaches, mentors, healthcare workers, law enforcement personnel, firefighters, and our military personnel. People judge the transparent hero as the most abundant in society, by far. Transparent heroes are everywhere. Yet they largely go unnoticed and are our most unsung heroes.

Paradox 4: The worst of human nature brings out the best of human nature. This paradox probably needs little explanation. Human-caused catastrophes such as the holocaust, the September 11th attacks, and the Virginia Tech shooting tragedy were fertile soil from which great acts of heroism blossomed. One year ago exactly, when Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords was shot outside a supermarket in Arizona, heroes stepped forward to protect Giffords from further harm and to prevent the gunman from targeting others. Stories of such heroism abound. Villainy always begets heroism.

Paradox 5: We don’t choose our heroes; they choose us. There is considerable research evidence supporting the idea of inherited cognitive capacities that interact with experience to produce the ways that people think and construct their worlds. To us, the idea of inherited, universal hero narrative structures that provide a ready basis for adopting heroes seems quite plausible. Our minds may equipped with images of the looks, traits, and behavior of heroes, as well as the narrative structure of heroism as outlined in Joseph Campbell’s (1949) hero monomyth. These archetypes may prepare us for seeing and identifying heroes. Thus our heroes may choose us as much as we choose them.

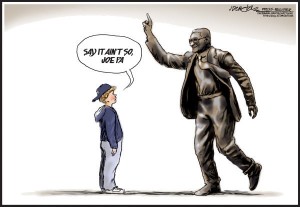

Paradox 6: We love to build up our heroes and we also love to destroy them. Our research shows that people are captivated by dramatic tales of underdogs who heroically prevail against the odds. Hero construction is inspiring and offers hope to all of us. But the reverse is also true: people also appear to crave the undoing of heroes. In fact, we suspect that this type of schadenfreude is heightened in hero-perception.  Our studies show that our greatest heroes cannot get away with anything less than near-perfect moral behavior. For this reason, many heroes are bound to fall from grace. People appear to believe in, and relish, a perverse law of heroic gravity: What goes up must come down.

Our studies show that our greatest heroes cannot get away with anything less than near-perfect moral behavior. For this reason, many heroes are bound to fall from grace. People appear to believe in, and relish, a perverse law of heroic gravity: What goes up must come down.

Paradox 7: We love heroes the most when they’re gone. Many studies we’ve conducted point to a rather morbid conclusion: As much as we love our heroes when they are around, we love them even more when they’re dead. We call this phenomenon the death positivity bias. This bias is seen in the factors that determine the perceived greatness of U.S. Presidents. Getting assassinated truly helps a president gain stature as a great leader. The greatest of our heroes must die to achieve their greatness.

– –

What accounts for these seven paradoxes? For us, the concept of heroism has proven to be slippery, mysterious, and surprising. To understand the paradoxes, we introduce the term intuitive heroism, which refers to people’s naïve beliefs about the way heroism operates. Intuitive heroism is similar to intuitive psychology or intuitive physics: What we think isn’t necessary so. Our naïve beliefs may lead us to underestimate the idiosyncratic nature of people’s hero choices. Intuitive heroism can make us oblivious to the impact of death in promoting heroism, and it can make us blind to our desire to see heroes fall as much as our desire to see them rise.

It is the misleading nature of intuitive heroism that has prompted us to undertake a more scientific approach toward understanding heroes. We invite you to learn more about these paradoxes at the Society for Personality and Social Psychology website. We’ve been delighted by all the surprising findings in our studies of heroism, and we look forward to uncovering – and understanding – many more.

References

Allison, S. T., & Goethals, G. R. (2011). Heroes: What they do & why we need them. New York: Oxford University Press.

Allison, S. T., Eylon, D., Beggan, J.K., & Bachelder, J. (2009). The demise of leadership: Positivity and negativity in evaluations of dead leaders. The Leadership Quarterly, 20, 115-129.

Carruthers, P., Laurence, S., & Stich, S. (2005). The innate mind: Structure and contents. New York: Oxford University Press.

Cialdini, R. B., Borden, R. J., Thorne, A., Walker, M. R., Freeman, S., & Sloan, L. R. (1976). Basking in reflected glory: Three (football) field studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 34, 366-375.

Dehaene, S. (1997, October 27, 1997). What Are Numbers, Really? A Cerebral Basis For Number Sense. Retrieved from http://www.edge.org/3rd_culture/dehaene/dehaene_p2.html

Dunning, D. (2011). He turned toward the gunfire. Personality and Social Psychology Connections. Retrieved from http://spsptalks.wordpress.com/2011/08/23/he-turned-toward-the-gunfire/

Goethals, G. R., & Allison, S. T. (2012). Making heroes: The construction of courage, competence, and virtue. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 46, 183-235.

Jung, C. G. (1917). The psychology of unconscious processes. In Long, C. (Ed.), Collected papers on analytical psychology. London: Bailliere, Tindall, & Cox.

Jung, C. G. (1969). Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Volume 9 (Part 1): Archetypes and The Collective Unconscious. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Pinker, S. (1991). Rules of language. Science, 253, 530-535.

Simonton, D. K. (1994). Greatness: Who makes history and why. New York: Guilford Press.

Like this:

Like Loading...

international education consultant with experience studying heroism in the classroom; Aaron Donaghy, who transformed the concepts of charity and heroism for students using the GO-effect; and Ann Medlock, who has spent decades discovering and promoting heroes through the Giraffe Heroes Program.

international education consultant with experience studying heroism in the classroom; Aaron Donaghy, who transformed the concepts of charity and heroism for students using the GO-effect; and Ann Medlock, who has spent decades discovering and promoting heroes through the Giraffe Heroes Program. association; Drew Jacob, professional adventurer, currently making his way from the source of the Mississippi to the mouth of the Amazon River under his own power; and Ethan King, who is changing the world through his project, Charity Ball, which provides soccer balls to kids living in poverty.

association; Drew Jacob, professional adventurer, currently making his way from the source of the Mississippi to the mouth of the Amazon River under his own power; and Ethan King, who is changing the world through his project, Charity Ball, which provides soccer balls to kids living in poverty.