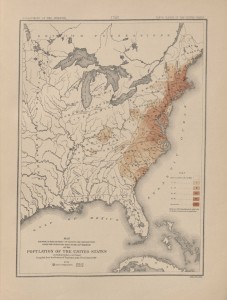

Maps are lies! They do not accurately depict reality; this is partly due to projection. Projection causes distortion in maps, which depend on the mapmaker. In the “Size of Africa,” map, created by Times Atlas, several other countries are placed on an outline of Africa. Due to the countries and even Africa possibly being distorted in this map, the cartographer includes the size in square kilometers of several regions to show how small each country is when compared to Africa; this allows the viewer to imagine the sizes of the regions along with seeing them. In this map, China, Western Europe, India, the United States of America, and Argentina, all fit onto Africa with plenty of room left over. Placed in the left over space is Finland, Norway, Sweden, and the British Isles. All these countries combined take up just about as much space as does Africa. The mapmaker chose to create this map to emphasize the vast differences between Africa and the other nations mainly regarding size.

In 2012, China maintained a population of 1.343 billion, India had 1.205 billion, and the United States contained 314 million. Though these are just three of the seven regions placed on Africa in the map, they have a total population of almost three times that of Africa. This is rather significant because Africa, the world’s second largest continent, contains a lesser population than that of India, a country about ten times as small as Africa. The fact that the cartographer chose not to include the population of each country and Africa is bewildering. Though power can be constituted by size, it is also created by population, especially on a map. A densely populated country usually has more strength than one with few people. For example, Greenland is very large, roughly 2.166 million square kilometers; however, it only has a population of a mere 56,840. This proves that size does not mean power.

According to Dr. David Salisbury, all maps are lies, they are outdated once they are created, and they contain power. This is, without a doubt, true. The “Size of Africa” map lies because it does not give all the information that is needed; in other words, there are silences that are not accounted for. This map is outdated because the size of the nations, both in population and in square kilometers, is always changing. Finally, this map contains power because it compares Africa to essentially the rest of the world; this allows for the comparison of supreme nations. For example, the United States, which is a lot smaller than Africa, contains more authority and influence. The supremacy of a country can be depicted through a map; however, the power of a map can be fabricated and partial. This is why many maps are considered to be propaganda. The cartographer chooses how he wants his map to look, and it can unknowingly persuade people. Every choice a cartographer makes is a political one; this map is extremely political because the cartographer chose to compare prosperous areas of the world to Africa.

Projection is a tool mapmakers can use to distort maps and alter the power maps contains. If one chose to critique the projection of the “Size of Africa” map, he would definitely ask why the map is so basic, why the regions chosen on this particular map were chosen, why population was not included, and why the United States is placed on top. Though this map is not as sophisticated or “geographic” as other maps in the sense that it does not, for instance, display mountains, rivers, and cities, it actually provides just as much, if not more, information than other maps, and although this map contains countless silences, it brings the same large amount of information, rhetoric, and accuracy as the others do. The reason why the United States is placed on the top is perhaps because the mapmaker is possibly American and biased; therefore he decided he must place “his” country on top. Or if the cartographer is not American, maybe he chose to place his country of residence on the map. Every country on this map was chosen for a reason. Even the continent was chosen for a reason. Why Africa? Why not the other six continents?

Africa, being the second largest continent, does not receive as much attention as it should. Whenever the United States is mentioned alongside Africa, it usually involves the United States helping out Africa by providing aid. This is just one example of how Africa is perceived as inferior and needy to the rest of the world. Western maps define Africa as a lacking continent that is essentially uncivilized and in desperate need of modernity. However, this perception of Africa is not true. Western maps hide the truth about Africa, along with several other nations, and many people believe the maps’ false assumptions. This is totally unfair because these standards were forced upon African countries by other nations that do not actually know what Africa is like. This creates a political problem because it causes other nations around the world to underestimate Africa. The cartographer purposefully chose to specifically place China, India, and the United States, on the map for many reasons; one very important reason is that these three countries are top world powers, and Africa, as a whole, is not one. The placement of these countries on Africa not only displays the obvious differences, such as size, but they also bring to light the more hidden differences, such as variances in power. This map also masks the diverse continent of Africa as one mass that is the same throughout. This also is far from the truth; while there are many African countries and nations in the midst of political chaos, there are many other prospering countries in Africa. This proves that there is a lot variety and diversity throughout Africa that is all hidden on the map.

This map, despite being basic and simple, constructs power that can be shaped in the viewer’s eyes. A map’s power derives from how it is perceived, and the fact that each person views a map differently shows just how much power a map can have. Another reason this map is so influential is because of the political choice of Africa, a very large and diverse place, being the map’s focus and the fact that Africa is compared to world powers. All in all, each map has the power to change the views of the looker, in both a positive and negative sense. Maps give people knowledge and provide new understandings, which is why cartography will never be diminished. Though the art of mapmaking has significantly weakened, the science of it has grown tremendously. With new technology, maps are doing things that they never could before. Soon maps, such as the “Size of Africa” map will be able to accurately reflect the power of Africa. As technology continues to progress and maps become more and more advanced, we as humans will stretch our limits, become smarter, and nothing will be deemed impossible any longer.

– S.K.

Works Cited

“Greenland Population Clock.” Country Meters. N.p., 2013. Web. 9 Oct. 2013. <http://countrymeters.info/en/Greenland/>.

Harley, J.B. The New Nature of Maps: Essays in the History of Cartography. Baltimore: John Hopkins University, 2001. Print.

“India: Size and Location.” Excell Up. N.p., 2009. Web. 2 Oct. 2013. <http://www.excellup.com/classnine/sstnine/indialocation.aspx>.

“Population of Africa 2013.” World Population Review. N.p., 2 Oct. 2013. Web. 9 Oct. 2013. <http://worldpopulationreview.com/africa/>.

Prelli, Lawrence J. A Rhetoric of Science: Inventing Scientific Discourse. Columbia: U of South Carolina, 1989. Print.

“Size of Africa.” Big Think. N.p., 20 Nov. 2006. Web. 2 Oct. 2013. <http://bigthink.com/strange-maps/35-the-size-of-africa>.

“Ten Countries with the Highest Population in the World.” Internet World Stats. Miniwatts Marketing Group, 10 Sept. 2013. Web. 2 Oct. 2013. <http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats8.htm>.

Turchi, Peter. Maps of the Imagination: The Writer as Cartographer. San Antonio: Trinity University, 2004. Print.

“What Is the Size of Greenland?” Ask. N.p., 2013. Web. 9 Oct. 2013. <http://www.ask.com/question/what-is-the-size-of-greenland>.

Wood, Denis. The Power of Maps. New York: Guilford, 1992. Print.

Zijlma, Anouk. “How Big Is Africa?” About. N.p., 2013. Web. 2 Oct. 2013. <http://goafrica.about.com/od/africatraveltips/ig/Maps-of-Africa/Map-of-Africa-Showing-True-Size.htm>.