This November 9th and 10th, 2013, a one-of-a-kind event will take place — The Hero Round Table Conference, to be held in Flint, Michigan. This is the first interdisciplinary conference on heroism ever held, and it has been masterfully organized by Matt Langdon, founder of the Hero Construction Company.

Matt Langdon (pictured below) has lined up a group of speakers whom he calls “an extraordinary group of experts from the fields of psychology, education, business, sports, philosophy, and entertainment”. Speakers from around the world will be sharing the latest developments on theories, research, and practices of heroism. And YOU can attend, too!

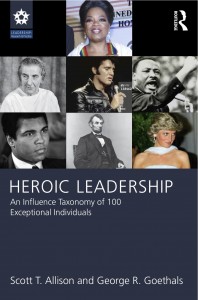

The star speaker is Dr. Phil Zimbardo, the world famous social psychologist who currently heads up the Heroic Imagination Project. Yours truly, Dr. Scott Allison of the University of Richmond, will also be speaking, having published two books on heroes and running a blog on real heroes and a blog on ‘reel’ heroes.

In the field of education, speakers will include Zoe Weil, the legendary humane educator, author, and speaker; Christian Long, an  international education consultant with experience studying heroism in the classroom; Aaron Donaghy, who transformed the concepts of charity and heroism for students using the GO-effect; and Ann Medlock, who has spent decades discovering and promoting heroes through the Giraffe Heroes Program.

international education consultant with experience studying heroism in the classroom; Aaron Donaghy, who transformed the concepts of charity and heroism for students using the GO-effect; and Ann Medlock, who has spent decades discovering and promoting heroes through the Giraffe Heroes Program.

Speakers from the realm of business include George Brymer, author of “Vital Integrities” and “Franciscanomics” and the creator of The Leading from the Heart Workshop; Dr. David Rendall, who shares his freak factor with audiences around the world as a speaker and author; Whitney Johnson, author of Dare to Dream, who suggests tapping into the power of the female hero’s journey; and Doug Knight, a non-profiteer making the connections between heroic action and the non-profit business world.

Additional speakers include Mike Dilbeck, the conference’s keynote speaker, who lays out the steps to heroic action in his everyday heroes presentations to audiences around the country; Jocelyn Stevenson, a star of children’s television and one of the pioneers for educating through television shows; Jeremiah Anthony, who, frustrated with the efforts of professional anti-bullying speakers, changed his school by himself; Pat Solomon, who created the documentary Finding Joe to honor the work of Joseph Campbell; and Dr. Ari Kohen, who teaches heroism at the University of Nebraska and is the host of the podcast, The Hero Report.

Finally, the conference is privileged to have speakers such as Nolan Harrison, who played defense in the NFL for 10 years and now works to help former players as a senior director at the NFL players  association; Drew Jacob, professional adventurer, currently making his way from the source of the Mississippi to the mouth of the Amazon River under his own power; and Ethan King, who is changing the world through his project, Charity Ball, which provides soccer balls to kids living in poverty.

association; Drew Jacob, professional adventurer, currently making his way from the source of the Mississippi to the mouth of the Amazon River under his own power; and Ethan King, who is changing the world through his project, Charity Ball, which provides soccer balls to kids living in poverty.

There will also be dozens of breakout sessions, featuring Chad Ellsworth from Building Heroes, Andrew Jones from Philosopher’s Stone, Sean Furey from the Hero Support Network, Greg Smith, from Agile Writers and Reel Heroes, Jensen Kyle from Moral Heroes, Elaine Kinsella from the University of Limerick in Ireland. Students will present posters on their work in the areas of altruism, the bystander effect, personality constructs, and pro-social behavior.

You can attend this great event by visiting the Hero Round Table website. Please check out the promo video: