By Richard Mercer

By Richard Mercer

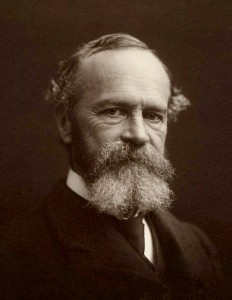

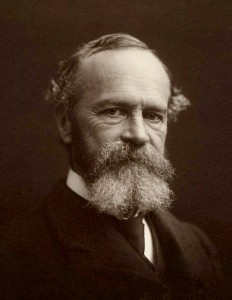

Let’s begin with a lecture given by William James toward the end of December, 1907, in New York City. Printed later under the title The Energies of Men, James identifies a serious, wide-spread malaise:

Most of us feel as if we lived habitually with a cloud weighing on us, below our highest notch of clearness in discernment, sureness in reasoning, or firmness in deciding. Compared with what we ought to be, we are only half-awake. Our fires are damped, our drafts are checked. We are making use of only a small part of our possible mental and physical resources.

Our natural vitality is constricted, something is missing. Many realize how much freer their lives might be, but find they are bound in, confined by only partially understood inhibitions, routines, and habits. Where are the keys that unlock and release our stifled energies?

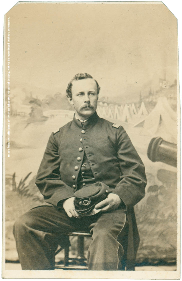

James first mentions crises. Consider this description of Lieutenant Henry Ropes of the 20th Massachusetts Volunteers at the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863 written by Captain H. L. Abbott:

(His) conduct in this action . . . was perfectly brave, but not with the bravery of excitement that nerves common men. He was absolutely cool and collected; . . . (his normal) slight impetuosity and excitability . . . sobered down into the utmost self-possession, giving him an eye that noticed every circumstance . . . ; a judgement that suggested in every case the proper measures, and a decision that made the application instantaneous. It is impossible for me to conceive of a man more perfectly master of himself, more completely noting and remembering every circumstance when the ordinary man sees nothing but a tumult and remembers nothing but a whirl.

Lieutenant Ropes’ actions embody conduct out of the ordinary; a new way replaces the old way of doing things with a decisiveness appropriate to the moment. His bravery is intriguing and inspiring.

Lieutenant Ropes’ actions embody conduct out of the ordinary; a new way replaces the old way of doing things with a decisiveness appropriate to the moment. His bravery is intriguing and inspiring.

James also mentions ideas — “ideas set free beliefs, and the beliefs set free our wills.” This young soldier’s experience can be seen as illustrating a state of being summed up in the Chinese neo-Daoist concept no-mind (wuxin). The person who experiences this is not mindless, but rather loses awkward self-consciousness and acts with appropriate and apparently effortless decisiveness. When such an idea, like any energy releasing abstract idea, is at work in an individual’s life, its effect is often very great. It acts as a kind of exhortation, something to inquire after, something to learn about. It is edifying.

In the context of Buddhist thought, connected to no-mind is another animating idea–the majestic concept of Enlightenment (anuttarasamyaksambodhi). Enlightenment in the Mahayana Buddhist view can be gradual or sudden. It can be the result of a lifetime of good behavior marked by restraint, study, and meditation or it can be instantaneous.

Sudden enlightenment is at the heart of the Lankavatara Sutra, compiled in Sanskrit in India somewhere between 300 and 450 CE. Brimming with invigorating ideas, it presents a remarkably modern looking psychological system suggesting enlightenment to be a healthy, human mind freed from countless abstractions and cumbersome habits.

Early in the sutra the Buddha warns Mahmati about the dangerous and delusive power of habitual reactions which are the source of greed, anger, and suffering.

So long as people do not understand the true nature of the

objective world . . . . they imagine the multiplicity of external

objects to be real and become attached to them . . . .

And a little later:

And a little later:

False imagination teaches that such things as light and dark,

long and short, black and white are different and are to be

discriminated; but they are not independent of each other;

they are only different aspects of the same thing, they are terms

of relation not of reality . . . . Mahamati, you and all Bodhisattvas

should discipline yourselves in the realization and patient

acceptance of the truths of emptiness . . . .

Freeing oneself from stale habits of thinking and the illusions of language games, a sudden and intuitive turning about takes place in the deepest seat of consciousness. At this moment, born from a state of mental concentration, one’s old, mortal mind is given up.

When the intellectual-mind reaches its limit . . . its processes of thought . . . must be transcended by an appeal to some higher faculty of cognition . . . . There is such a faculty in the intuitive mind, which is the link between the intellectual mind and Universal mind.

With egotism greatly diminished and gradually disappearing, the Bodhisattva becomes master of himself and of a life of spontaneous and radiant effortlessness.

The Diamond Sutra, compiled in India in Sanskrit perhaps around 300 CE, provides a dramatic illustration of a sudden enlightenment experience. In it the Buddha teaches Subhuti, a well-known disciple and Arhat, lessons in the perfection of wisdom (prajnaparamita) and emptiness (sunyata). Throughout the short sutra a wide variety of important, traditional elements in early Buddhist and Mahayana thought are subjected to a pattern of deconstruction. They are declared to be empty–not eternal verities, but relative.

Take for example the Jataka tales which were extremely popular and influential. These are tales of the Buddha’s many, many previous lives before he became the Buddha Shakyamuni. In a number of these he is in the form of an animal that sacrifices itself to provide food for someone who is starving. In others he is in human form performing prodigious acts of sacrifice that include giving away possessio ns and even family members. Suicide to save others figures in a number of the stories. These tales provided an hyperbolic ideal of selfless behavior for early Buddhists and Shakyamuni undoes them along with other Buddhist mainstays.

ns and even family members. Suicide to save others figures in a number of the stories. These tales provided an hyperbolic ideal of selfless behavior for early Buddhists and Shakyamuni undoes them along with other Buddhist mainstays.

The Buddha said: If some woman or man were to sacrifice

as many of their own bodies as there are grains of sand in

Ganges River, Subhuti, and if someone were to learn just

four lines from this sutra and teach it to others the merit of

teacher would exceed that of the others by an immeasurable amount.

At this moment, in a flash, Subhuti comprehends the new ideal.

Venerable Subhuti, listening to this was shocked into a deep

understanding of the meaning of this teaching; bursting into tears

and wiping them away as he continued to weep, he said how

well the Buddha has taught these lessons. A new level of

cognition has been produced in me.

It is not unusual for sutras to conclude with a general enlightenment experience accompanied by universal rejoicing, but this is different–it is one disciple moved to tears. And we’re not finished. The explosive power of prajnaparamita’s doctrine of emptiness is frightening. BOOM! Everything crumbles into the rubble of paradox and relativity.

The Buddha said to Subhuti: . . . If there is a person who,

listening to this sutra, is not frightened, alarmed, or disturbed,

you should know him as a wonderful person. Why? Because

what the Buddha has taught as parjnaparamita, the highest

perfection, is not the highest perfection and therefore it is called

the highest perfection.

Immediately out of the ruins, however, arise two virtues that have escaped the general collapse, patience and charity. True to form Shakyamuni says the perfection of patience is really no perfection and that’s why it’s called the perfection of patience. The same holds for charity. This realized, the result is wonderful.

The Buddha said to Subhuti: When a bodhisattva practices

(patience and) generosity without depending on form, he is like

someone with good eyesight walking in the bright sunshine

–he can see all shapes and colors.

The experience is expansive. The whole world opens up becoming fresh and new.

The idea that sparks conversion in the Lanka and the Diamond Sutra is emptiness (sunyata)–a radical relativity. There is no Truth and that’s the Truth. This is the perfection of wisdom (prajnaparamita). Both sutras declare that awareness of  relativity is liberating and energizing, but at the same time a power drawing people together. We simply see the world as it really is. William James echoes this:

relativity is liberating and energizing, but at the same time a power drawing people together. We simply see the world as it really is. William James echoes this:

Truth happens to an idea. It becomes true, is made by events.

Its verity is in fact an event, a process. We say our ideas “agree”

with reality when they lead us through acts and ideas . . . to other

parts of experience . . . . The connexions and transitions come to us from point to point as being progressive, harmonious, satisfactory.

James expresses an idea Mahamati and Subhuti might well understand but never put the way he puts it.

True ideas lead to consistency, stability, and flowing human

intercourse. They lead us away from eccentricity and isolation,

from forced and barren thinking.

Our energies are unbound. We arrive at the paradoxical condition of no-mind (wuxin) in which our thinking is free from attachment working smoothly at liberty to come and go en rapport with every circumstance and to render help to every person in the most appropriate way.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

This essay is Richard Mercer’s third analysis of heroism from the Buddhist perspective. His first essay focused on the Bodhisattva. Mercer has been a Visiting Instructor of English and Core (especially Edgar Allan Poe and Samuel Beckett) at the University of Richmond. He has studied Buddhism since the early 1990s. Only recently has he realized that the Bodhisattva ideal is a wonderful and practicable model to follow.

Like this:

Like Loading...

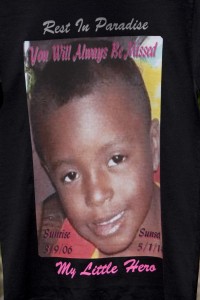

Ginny and Natalie. They quietly touched the lives of many people in ways that will have a ripple effect throughout eternity. Kindness begets kindness, I am sure of it.

Ginny and Natalie. They quietly touched the lives of many people in ways that will have a ripple effect throughout eternity. Kindness begets kindness, I am sure of it. citizens are now feeling. Summing up Marty perfectly, a makeshift sign placed outside Marty’s home reads, “Pound for pound, year for year, few greater heroes if any.”

citizens are now feeling. Summing up Marty perfectly, a makeshift sign placed outside Marty’s home reads, “Pound for pound, year for year, few greater heroes if any.”