In the early 20th Century, men and women were considered quite different animals and the social roles assigned to them reflected that belief. Women were expected to keep house and raise children while the adventures of invention and exploration were left to the men. Going beyond those expectations was not encouraged, and often punished. Most people conformed to those limitations, but some were not content to be grounded–- some, like Harriet Quimby, felt compelled to find new horizons.

Long before being bitten by the aviation bug, Quimby led an independent and liberated lifestyle that was the envy of many women of her day. An unmarried woman in New York City, she was a successful writer, turning out articles for the magazine Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly for many years, as well as several screenplays for DW Griffith in the early days of Hollywood. She was an “old maid” of thirty-five when she attended an international aviation tournament on Long Island and met famous aviator John Moisant (whose sister was to quickly follow in Quimby’s footsteps). Her first flying lessons soon followed. A headline in The New York Times, typical of the attitudes of that era, stated “Woman in Trousers Daring Aviator; Long Island Folk Discover That Miss Harriet Quimby Is Making Flights at Garden City.”

A year later, in 1911 (more than a decade before Amelia Earhart), Quimby became the first woman in the United States to earn an aviator’s certificate. Her friend Matilde Moisant became the second shortly thereafter.

But Quimby was not yet finished with making history.  The next year, in April of 1912 (the day after the sinking of the Titanic), she became the first woman to pilot an aircraft across the English Channel.

The next year, in April of 1912 (the day after the sinking of the Titanic), she became the first woman to pilot an aircraft across the English Channel.

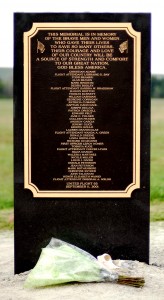

Sadly, her next milestone was a tragic one. In July of 1912, she attended, and participated in, The Third Annual Boston Aviation Meet at Squantum on Dorchester Bay. While circling Boston Harbor, with event organizer William Willard as a passenger, her plane experienced unexpected turbulence and both pilot and passenger fell to their deaths, the plane crashing on the beach.

A century has now passed since the untimely death of Harriet Quimby. The romantic figure of the first aviatrix in her distinctive purple flight suit is all but forgotten. But thanks to her and others like her, the opportunities for women in society have expanded to a degree that few in her lifetime would have believed possible. Yet it is still true, well into the 21st Century, that both women and men are pressed to limit themselves to roles defined by their gender. Most will conform. But some will not be content to be grounded. And thanks to those like Harriet Quimby, their flight may be a little smoother.

– – – – – – – – – – –

Rick Hutchins was born in Boston, MA, and has been an avid admirer of heroism since the groovy 60s. In his quest to live up to the heroic ideal of helping people, he has worked in the health care field for the past twenty-five years, in various capacities. He is also the author of Large In Time, a collection of poetry, The RH Factor, a collection of short stories, and is the creator of Trunkards. Links to galleries of his art, photography and animation can be found on http://www.RJDiogenes.com.

This is Hutchins’ fifth guest blog post here. His first two, on astronaut and scientist Mae Jemison and the Fantastic Four’s Reed Richards, appears in our new book Heroic Leadership: An Influence Taxonomy of 100 Exceptional Individuals.