What is the recipe for heroism? Because heroism is in the eye of the beholder, there is no set list of ingredients. But research reveals that especially powerful and iconic heroes are perceived to possess at least a few of the following characteristics: (1) They have an exceptional talent; (2) They have a strong moral compass; (3) They incur significant risk; and (4) They make the ultimate sacrifice while helping others.

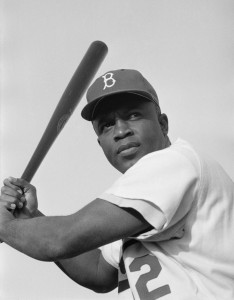

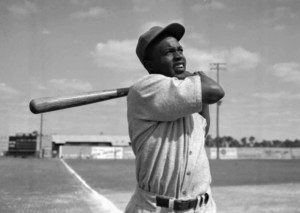

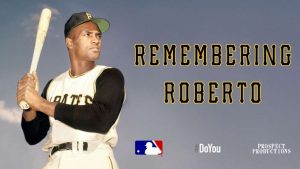

Roberto Clemente was one of those rare and extraordinary individuals who beautifully, and tragically, fit this mold of a great hero. Today, nearly five decades after his untimely death, Clemente’s accomplishments, selflessness, and charisma make him an unforgettable hero.

It was the way he lived — and the way he died — that made Clemente an extraordinary individual.

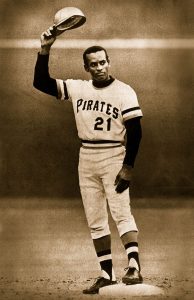

Former major league baseball commissioner Bowie Kuhn once said of Clemente, “He had about him the touch of royalty.” Duane Rieder, Director of the Clemente museum, said, “There was something about him that was magical.”

Dozens of schools, hospitals, parks, and baseball fields bear his name today. What did Clemente do to earn such veneration?

We won’t delve into many details of Clemente’s genius on the baseball field. We will say that while playing for the Pittsburgh Pirates from 1955 to 1972, he won multiple batting titles, gold glove awards, world championships, and most valuable player awards. He hit for average and he hit for power. He possessed great speed and a rocket of a throwing arm.

Los Angeles Dodgers announcer Vin Scully once said, “Clemente could field a ball in New York and throw out a guy in Pennsylvania.”

People who knew Clemente argue that as great as he was a player, he was an even better human being. When traveling from city to city as a player, he routinely visited sick children in local hospitals. According to author David Maraniss, Clemente spent significant time in Latin American cities, where he would often walk the streets with a large bag of coins, searching out poor people.

Wrote Maraniss: “To the needy strangers he encountered in Managua, Clemente asked, “What’s your name? How many in your family?” Then he handed them coins, two or three or four, until his bag was empty.”

Clemente once said, “Any time you have an opportunity to make things better and you don’t, then you are wasting your time on this Earth.”

Clemente, a native Puerto Rican, also overcame significant adversity. He grew up in poverty. He faced discrimination, living in an era that tended to be intolerant of non-White, non-English speaking people. Because baseball at the time was dominated by Willie Mays, Mickey Mantle, and Hank Aaron, Clemente was often overlooked in discussions of great athletes. Clemente was also hampered throughout  his career by chronic back and neck problems. Yet he still managed to accumulate an exemplary record of achievement on the baseball field.

his career by chronic back and neck problems. Yet he still managed to accumulate an exemplary record of achievement on the baseball field.

To this day, the manner in which Clemente died still brings people to tears. In late December of 1972, he heard that Managua, Nicaragua, had been devastated by a massive earthquake. Clemente immediately began arranging emergency relief flights from Puerto Rico. He soon learned, however, that the aid packages on the first three flights never reached victims of the quake. Apparently, corrupt officials had diverted those flights. Clemente decided to accompany the fourth relief flight to ensure that the relief supplies would be delivered to the survivors.

The airplane he chartered for a New Year’s Eve flight, a Douglas DC-7, had a history of mechanical problems and was overloaded by 5,000 pounds. Shortly after takeoff, the plane crashed into the ocean off the coast of Puerto Rico, killing the 38 year-old Clemente and three others.

News of Clemente’s death spread quickly. In Puerto Rico, New Year’s Eve celebrations ground to a halt. “The streets were empty, the radios silent, except for news about Roberto,” said long-time friend Rudy Hernandez. “Traffic? Except for the road near Punta Maldonado, forget it. All of us cried. All of us who knew him and even those who didn’t wept that week.”

Nick Acosta, another friend, summed up the fateful night that Clemente died. “It was the night the happiness died,” he said.

Check out this short video showcasing Clemente’s selfless heroism:

– – – – – – – – –

By Meghan Dillon

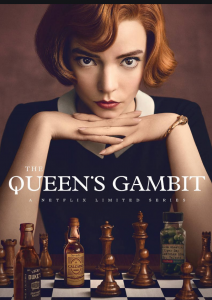

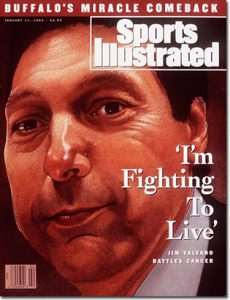

By Meghan Dillon Jimmy V could live out his aspirations. One of the many reasons I see Jimmy V as a hero is that, along the way to accomplishing his dream of winning a national championship, he took on a personal ideology of living that would allow him, a seemingly ordinary man, accomplish things that we see as extraordinary. This ideology would help him to innumerable victories.

Jimmy V could live out his aspirations. One of the many reasons I see Jimmy V as a hero is that, along the way to accomplishing his dream of winning a national championship, he took on a personal ideology of living that would allow him, a seemingly ordinary man, accomplish things that we see as extraordinary. This ideology would help him to innumerable victories.