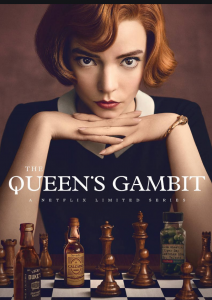

The Queen’s Gambit is one of those miniseries that shouldn’t work but somehow does. What could be less exciting than watching two people sit at a table silently playing a board game that most of us don’t really understand?

But here’s the secret to The Queen’s Gambit’s success: It tells one hell of a hero’s story.

And as we’ve been saying for years, as long as a story captures the beauty and inspiration of the hero’s journey, and does so in a new and interesting way, it will find an audience.

Let’s start with our hero, Beth Harmon. We really shouldn’t like her. She’s cold, aloof, self-destructive.

Why are we drawn to this hero? Well, we all know that people love an underdog, and Beth is an underdog in five different ways. Maybe even six. It’s a bit sledgehammered, but it works.

First, Beth is a woman competing in a man’s world. Second, she’s not only an orphan, but a double-orphan. Third, she’s an addict. Fourth, because of the severity of her losses, she’s emotionally stunted. Fifth, she is poor.

We can also add that she is an American playing a game that is dominated by the Russians.

Like all good heroes, Beth has a superpower: She is a brilliant chess player, possessing more raw talent than anyone.

Beth also has a superpower within the superpower: She can mentally play out the winning moves of a chess game on the ceiling of any room she is in.

Like all good heroes, Beth has her kryptonite: She is hopelessly addicted to drugs and alcohol. Her pain cuts deep — hence her need to self-medicate with sedatives.

Beth thinks she can only win at chess when she’s drugged up. All good heroes are missing something important and must find these missing qualities to succeed. Beth lacks self-insight, self-regulation, and courage.

So the set-up of the story is clear. If only Beth can get out of her own way, she can rule the chess world. That’s a big “if”. Especially for a person who doesn’t attract friends easily.

The good news is that every hero receives help, even Beth. Her mentor is a janitor at the orphanage named Mr. Shaibel. Later Beth receives help from former competitors whom she has defeated: Townes, Harry, Benny, and the twins Matt and Mike.

Later Beth receives help from former competitors whom she has defeated: Townes, Harry, Benny, and the twins Matt and Mike.

On the eve of Beth’s match with the great Soviet champion Borgov, her childhood friend Jolene shows up. Beth benefited from Jolene’s stable, sensible influence years earlier and needs it now more than ever. Jolene offers to pay for Beth’s travel to Russia.

Returning to the orphanage to attend Mr. Shaibel’s funeral, Beth learns that her old mentor had followed her career closely and supported her from afar. This discovery reduces her to tears — her first show of emotion.

The ice has cracked. Beth is now fully human and ready to become her best self.

All good hero stories end with the hero returning home. The Queen’s Gambit portrays this return home in a wonderful and unique way. After defeating Borgov in Moscow, she mingles among a throng of Mr. Shaibel-like old men playing chess in a Russian park.

She has returned “home”, so to speak, only as poet T.S. Eliot once said, home is now completely different. The hero now sees home with a new set of eyes.

By playing chess with one of the Russian Mr. Shaibels, Beth is now giving back what was once given to her. Once transformed, the hero helps transform others. And as Joseph Campbell said, the hero is now in union with all the world.

Beth Harmon was a pawn who became a Queen. You rarely see a hero’s journey better than that.

– – – – – – – – – – –