The common persona of a hero is that of the savior of a vast city. With the new millennium, however, our image of heroes has been changing. An important question that we should all be asking ourselves is this: How do we distinguish real heroes from phony ones, especially in our confusing modern times?

Heroes come in many shapes and sizes but the precise definition, image, and character of a hero should be shown through all the colors of light. We should all agree on a few defining principles of heroism: Heroes exceed what is expected of them, they make a positive impact on people’s lives, and they rise above and beyond the ordinary.

We have our daily heroes who barely get any recognition, the most prominent of which are school teachers who mold the minds and lives of young people. Heroic teachers live on small annual paychecks compared to most people who pursue non-heroic careers. Higher paying jobs may require more schooling but why do we associate bigger paychecks with heroic merit? The people in our society with the highest paychecks seem to receive the greatest recognition of their so-called “heroism” at work.

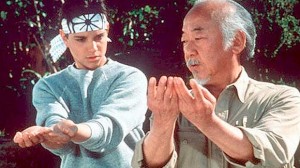

When assessing heroism, it is important to consider motives. Lawyers, police officers, and firefighters are the “protectors” of society, you might say. They fight fires and criminals — but do they do it out of the kindness of their hearts or for the money?  If they are motivated by money, would you put your life in their hands? The genuine heroes seek to help others; they don’t serve others to acquire material gain. True heroes are caring, compassionate individuals who want to save and improve people’s lives independent of external rewards.

If they are motivated by money, would you put your life in their hands? The genuine heroes seek to help others; they don’t serve others to acquire material gain. True heroes are caring, compassionate individuals who want to save and improve people’s lives independent of external rewards.

Heroism is contagious. One act of heroism inspires another individual to act heroically, as well as another, creating this wonderful domino effect. A single heroic action can have ripple effects that can transform an entire community; the community then affects the city, and the city can inspire a nation and the world. Never underestimate the cumulative social impact of heroism.

Heroism in the Merriam-Webster Dictionary has several definitions:

1 : A mythological or legendary figure often of divine descent endowed with great strength or ability.

2 : An illustrious warrior.

3: A man admired for his achievements and noble qualities.

4 : One who shows great courage.

Notice that heroism is not limited by gender. Nor is it restricted by race, occupation, age, height, or weight. Anyone can be a hero, whether a mythological figure or an ordinary citizen. Adopting this broad perspective of heroism makes it clear that heroes need not have a title, a degree, or a large paycheck. Heroism only requires a willingness to selflessly serve others. And YOU can be that hero.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Chelsea Chico is a first-generation Colombian-American studying Biology with aspirations to become a surgeon or dentist. She is 18 years old and completing her first year of post-secondary education. Some of the things she is passionate about are: electronic music, soccer, family, and standing up for what she feels is right.