By Dom Harrington

My family has just concluded a four-hour conversation about race in America — from vehemently disagreeing about the value or lack thereof of #BlackLivesMatter to stumbling upon the infamous Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. vs. Malcolm X debate to finally ending with our different conclusions regarding whether or not the black community has achieved equality.

This past week, I had the distinct privilege of witnessing my older brother, Claude Lee Harrington II, graduate with honors from Washington University in St. Louis. I was joined by my parents, my aunt, and my two maternal grandmothers. My family has been in this country for generations, as far back as the 18th century. Therefore, both my maternal and paternal sides were slaves until 1865. Then, they were sharecroppers. Then my grandparents, on both sides, moved from Mississippi to Indiana as a part of the Great Migration. Therefore, it was an honor to attend this momentous occasion, hands interlocked, eyes swelling with tears as my brother’s name was called to get his diploma.

In our conversation, my father claimed that the very fact that my brother graduated from college and is going to law school is progress and shows that the Civil Rights Movement was a success. In response, I asked the questions that prompted this post: What do real success and progress mean? Who determines the answers to these questions? These questions made me reflect not only on the collections I’ve analyzed through this project but how the work that we are doing adds to this enduring struggle for justice and progress.

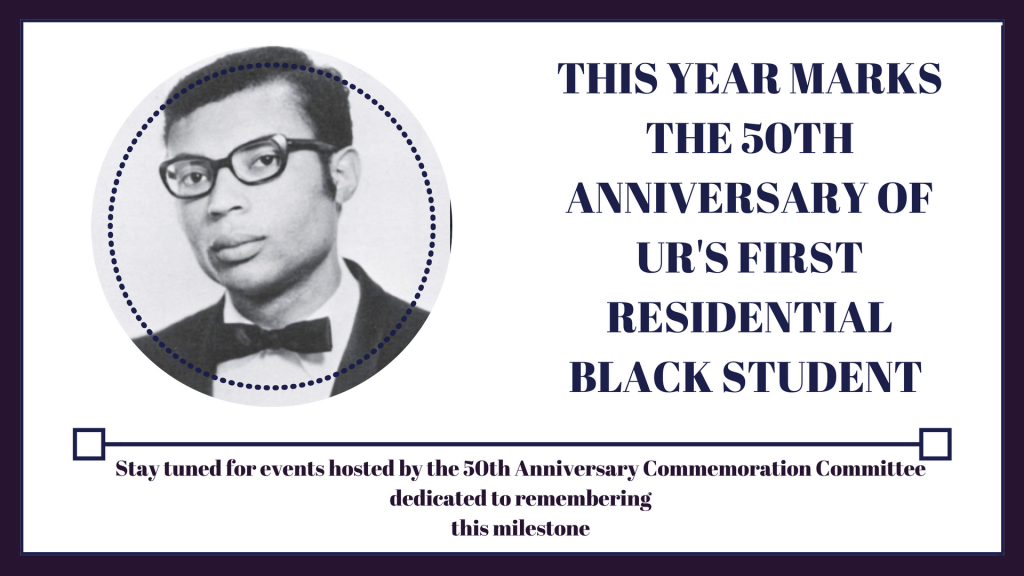

This past fall I worked on President Modlin’s Papers. In the beginning, my team members and I had a hard time figuring out what exactly to do with the documents contained in the folder we were assigned. However, this course and project taught us that it’s incumbent upon archivists to be able to read against the grain and challenge dominant narratives that rest within the documents that they are provided. In the end, we examined this collection with a critical lens to see if integration was “inevitable” at the University of Richmond or not. Even though my team focused on this university and its road to integration, our work informs the history of this country and its never-ending road to progress. This is exactly the reason why I am thrilled to be working with this project this summer.

Like graduations, the Race and Racism project will mean different things to different people. To me, as a black female student, this project is both cementing my story, and those who have come before me, unheard and unknown. Dominant narratives like that of progress need to be challenged, especially now in the age of alternative facts. The thing about progress is, to know how far we have come, or how far we have progressed, we must know where we have been. To much dismay, I’m not convinced that the majority of this country knows as much about where we have been, regarding our racial history than they should. With an acknowledgment of where we have been, we could have much more fruitful conversations about where we are today. It is 2017, and we still can’t agree on whether or not the Civil War was about slavery or the states’ rights. Therefore, it is 2017, and we have Americans protesting the removal of statues of Confederate war heroes. Perhaps if the country, as a whole, were more knowledgeable about the history of slavery and the ideologies in which it was grounded that persist today, we wouldn’t have this issue.

It is certainly progress that my brother, a black male, has graduated college. Is it true progress if he will have to be twice as good, in every aspect, for the rest of his life? Progress isn’t linear or unidimensional. It’s messy, and it’s difficult, but so are race and racism. Therefore, we have work to do. We must ask the right questions, challenge the right institutions, and uncover the stories voices of those silenced and devalued, we can take down as many monuments as we want and talk until we lose our voices, but until we truthfully and critically understand where we as a country have been with race and racism, actual progress is impossible. So, what better place to start with these questions than the site of memory that is the archive?

Dominique “Dom” Harrington is a rising junior majoring in American Studies and minoring in Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies. She worked with the Race and Racism project for the Fall 2016 seminar, Digital Memory and the Archive. This summer, she is thrilled to continue working with this project remotely from her hometown of Indianapolis, Indiana.