by Dom Harrington

Dom Harrington is a senior from Indianapolis, Indiana majoring in American Studies and minoring in Women, Gender, and Sexuality studies (WGSS). She has been involved with the Race & Racism Project since 2016 and is currently serving as an advisory board member and as the chair of the 50th Anniversary of Residential Desegregation Committee. As a student, she is also an Oldham Scholar, Oliver Hill Scholar, member of the Dean’s Student Advisory Board, a research assistant for Dr. Kristjen Lundberg, a peer adviser and mentor, and a Bunk contributor. She hopes to go to graduate school for mental health counseling.

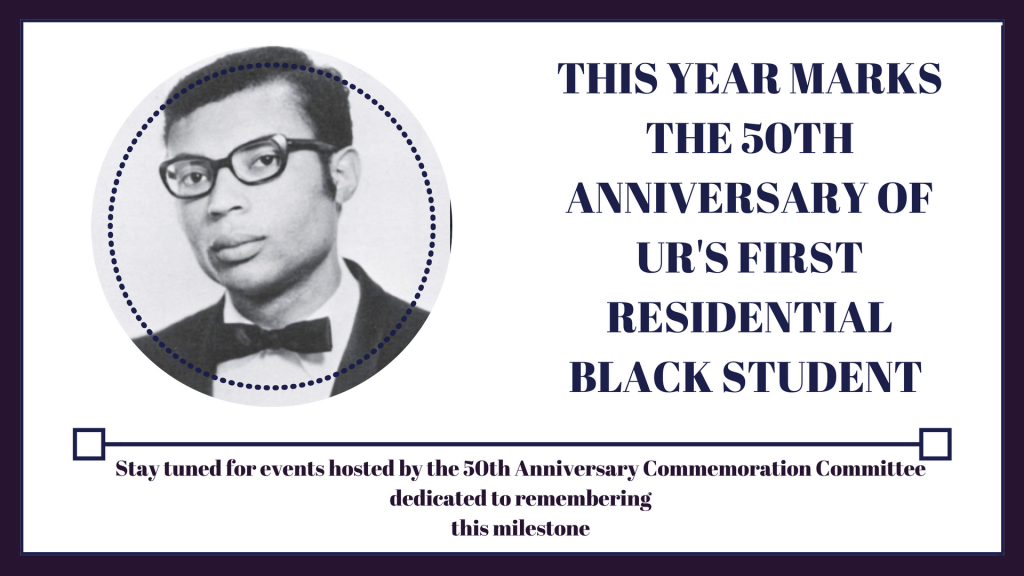

This year, 2018, marks some momentous “fiftieth” anniversaries for this country. It marks the fiftieth anniversary of the assassinations of Sen. Robert Kennedy and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., along with the fiftieth anniversary of the first interracial kiss to air on American television. However, 2018 is an especially important year for this university because it marks the fiftieth anniversary of residential desegregation on the University of Richmond’s campus. I’ve spent the past few months working with dedicated students trying to tackle the significant task of commemorating this occasion, and I’m incredibly excited for all that is yet to come this school year. With this, I’d like to thank the Race & Racism at the University of Richmond Project for giving me the space to share my thoughts on why commemoratory events surrounding this pivotal anniversary are not only nice, but necessary.

Fifty years ago this fall, the University of Richmond was forced to residentially integrate campus–or officially accept a black student–and in turn allow them to live on campus for the first time. To briefly set the scene: The University desegregated its non-residential downtown school, University College, in the spring of 1964. This happened ten years after Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka was decided, which mandated the desegregation of public schools. Despite this being a long time, Virginia was also the state of massive resistance, so compliance didn’t have overwhelming support at this time. The University of Richmond’s status as a private institution allowed the administration to decide when integration would occur. The University hoped that this 1964 step of desegregating would be enough, however, from 1964 to 1968 an increasing number of internal and external pressures, including students, alumni, Baptist organizations, and even the United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, amounted to essentially forcing the University to desegregate campus.

Thanks to archival digging, we know about the first black student to go to University College. His name is Walter Carpenter, yet we certainly don’t know as much as we should. Furthermore, we don’t know anything about the other black folks who attended University College from 1964 to 1968. The first black Westhampton College women were Madieth Malone, Isabelle Thomas, and Josephine Ethel Otey. These women were day students—commuting to campus instead of living in the dorms. The first black person to live on campus is named Barry Greene, and he graduated in 1972.

Greene’s story, as well as the other pioneering black alumni of UR, has too long been forgotten. It’s high time we remember them, and our history, for a few reasons. First, acknowledging those who have come before us is crucial to chipping away at the wrongdoings of the past. Walk around this campus, and you’ll see who we remember, and who we don’t. You’ll also see what we remember and what we don’t. For instance, take the statue of E. Claiborne Robins in between Ryland Hall (a building itself named after an enslaver), and Weinstein Hall. Robins’ business sold an intrauterine contraceptive that led to the deaths of 21 women and over 13,000 women became sterile.

The point of this blog post is not to spark a debate about what should be done about current sites of memory, but rather to point to the fact that there’s a lacuna in remembrance on this campus. We can remember these problematic figures from our past, but don’t remember pioneering black students, faculty, and staff. We can remember this University’s cherished traditions, like ring dance, yet still have little to no idea about the history of race and racism at this institution. We must ask ourselves who and or what are we forgetting? It’s about time we remember and honor those who led the way in desegregating this campus, and paved the way for the diverse student body that we have today.

Not only is acknowledging all of the history of this University important, but it has completely reshaped how I see its current challenges, and how I envision solutions for the future. For instance, curating an exhibit on the outside influences that pushed the university to integrate has completely reshaped my conceptualization of the “inevitability” of progress. This reconceptualization has given me insight on how to make change at this university–not through passivity, but through firm pressure from within and outside an institution. We could simply look at the past few years, and how it took pressure from students, faculty, alumni, and national media attention to finally get this University to make overdue changes regarding Title IX and sexual assault on campus.

Finally, perhaps if folks were more aware of where we’ve been, regarding race and racism, we could have more fruitful conversations about the state of race on campus today. For instance, if folks knew about the racial politics of hiring here, then maybe more students would make connections to what folks in administrative and faculty roles vs. service roles look like on campus. In addition, if more students knew about the history of black student life, they wouldn’t be surprised at the recent Princeton Review rating that placed UR at #9 for having the least race/socio-economic status mixing among students. (Even though this University touts its commitment to diversity whenever it can.)

Barry Greene himself recently discussed his experiences here in an oral history interview with the Race & Racism Project conducted by Ayele d’Almeida, Mysia Perry, and Jacob Roberson. Greene recounted feeling uncomfortable occupying space on this campus both inside and outside of the classroom. Although some peers, particularly Jewish students, brought him into their friend group, navigating where to sit in the dining hall was a struggle because a number of students didn’t want to sit with him. Taking this into account and knowing that black students are still faced with difficulty in trying to carve out spaces in an institution that wasn’t built with them in mind, it’s disheartening to see just how much things have changed, but have also remained the same. It’s because of this fact that memory within our community is so important.

Those who’ve come before us deserve their place in the history of this university, especially if they didn’t receive it while they were here. This past August, another group of black freshmen arrived on this campus–wide eyed and bushy tailed. The events we are planning, including, but not limited to, a Meet at the Museum on October 18, and a CCE Brown Bag and a Homecoming Event entitled “A Story Unfolding” on November 2 are important because not only will we be acknowledging what needs to be acknowledged but we are ensuring a place on this campus for current students in ways that weren’t afforded to those who’ve come before us. We are ensuring that our community is more aware, and through this awareness we can only hope for a better and stronger University of Richmond community. As a current black student, to the first four black students on this campus: Josephine Ethel Otey, Isabelle Thomas, Madieth Malone, and Barry Greene, I suppose I only have one thing left to say: thank you and we see you.

Please visit memory.richmond.edu for more information.