On March 16, 2018, five undergraduate students who have worked with the Race & Racism at the University of Richmond Project had the opportunity to present at the Lemon Project Symposium at the College of William and Mary. The panel, entitled “Seeing the Unseen and Telling the Untold: Institutions, Individuals, and Desegregating the University of Richmond,” was moderated by Dr. Nicole Maurantonio and featured Dominique Harrington, Madeleine Jordan-Lord, Elizabeth Mejía-Ricart, Jennifer Munnings, & Destiny Riley. Below you will find the text and slide images of Dominique Harrington’s presentation, focusing on the research she conducted as a 2017 A&S Summer Research Fellow with the project. Click here to read more of her writing from last summer, and here to explore her exhibit “Faculty Response to Institutional and National Change (1968-1973).”

Dominique “Dom” Harrington is a rising senior from Indianapolis, IN majoring in American Studies and minoring in Psychology and Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies. She is a part of the Dean’s Student Advisory Board, Students Creating Opportunities, Pride, and Equality (SCOPE), and she is both an Oldham and Oliver Hill Scholar. She has worked on the Race & Racism Project for two years and looks forward to continuing to work for the project during her final year at the University. Last summer, she completed a digital exhibit on faculty response to institutional and national changes from 1968-1973.

Thank you Dr. Maurantonio and thank you to William and Mary for putting on this wonderful symposium. I’ve been involved with the University of Richmond Race & Racism Project since the Fall of 2016, however, I’d like to focus my presentation on the work that I completed last summer.

I’m going to start by giving a brief overview of the work that I’ve done with the project, then I’ll give you an example of one of the favorite documents that I worked with, and then I’ll end with my reflections on the importance of the work we’ve been doing.

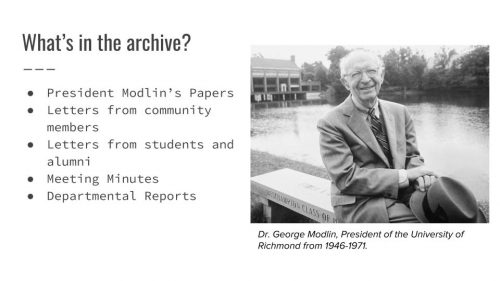

The majority of the documents I worked with were from President George Modlin’s papers during his tenure as president at the University from 1946-1971, which are part of the collection at the Virginia Baptist Historical Society, an archive on campus.

Within this collection, there were letters from faculty, alumni, students, and educational leaders like the Chairman of the Special Committee on Racial Discrimination of American Law Schools. This committee navigated how to deal with integration at member universities. There were also a number of annual departmental reports which I found to be particularly interesting. So much so, that they ended up serving as a springboard for creating my final project.

As I examined these reports, I noticed that the Race & Racism Project to that point had highlighted students, employees, and even past presidents, like I did with the exhibit that Madeleine already presented on. However, major players on the university campus were missing: faculty.

Within the reports that faculty members submitted between 1968-1973, I noted that faculty were responding to three issues: religious discrimination, integration, and student dissent. This timing is important.

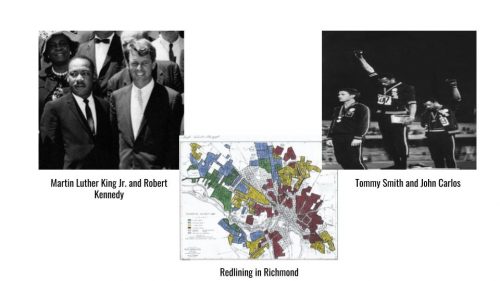

In 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy were assassinated, racially restrictive covenants became illegal in real estate, and two Olympic athletes, Tommie Smith and John Carlos, staged the iconic silent protest by raising their fists instead of placing their hands on their chests during a medal presentation ceremony in Mexico City.

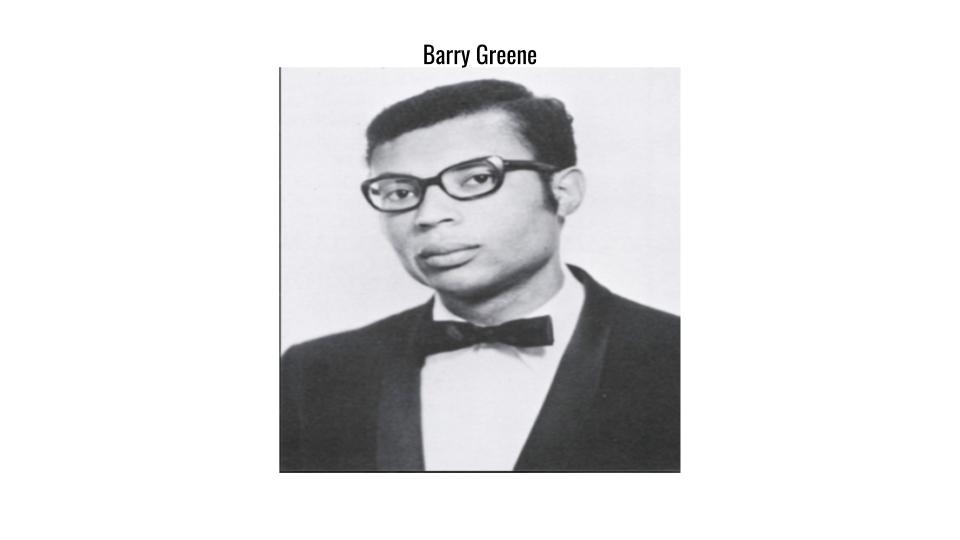

That same year, in 1968, the University of Richmond enrolled its first residential black student, Barry Greene, on its main campus.

Barrier shattering changes filled the rest of these years as well, particularly with the rise of liberatory movements for women, black folks, the LGBTQ community, and even the anti-war movements that swept the nation.

Because of my major, I’ve had the opportunity to study these decades through both national and state level lenses, however it begged a driving question for my research with this project: How were faculty at my university responding and engaging with these historic changes?

The faculty I examined belonged to one of three colleges: Westhampton College, Richmond College, and University College on Lombardy Avenue (or UCLA). Westhampton College, established in 1914, and Richmond College, incorporated in 1840, were the women’s’ and men’s’ colleges, respectively. UCLA was a satellite campus downtown to connect UR to the business community of Richmond. Before Richmond College was officially established in 1840, it was a Baptist Seminary; these Baptist roots shaped every aspect of the University, that is, until the 1960s and 1970s when both faculty members and students began challenging the constraints, and sometimes discrimination, that came along with this Baptist affiliation.

The digital exhibit I curated this summer grapples with a few driving questions, but the main one was : (1) What role did faculty play in challenging, perpetuating, and/or remaining complicit in systems of oppression?

From my questions, I argued that not only do faculty need their place in narratives of Race & Racism at the University of Richmond, they were also responsible for being complicit in, and in some cases, actively resisting systems of oppression that shaped the campus environment.

Because of time constraints, I’d like to just share one portion of my exhibit that I found to be particularly interesting.

As I mentioned, the 1960s and 1970s were characterized by dissent. Oftentimes, the breeding grounds for this dissent were college campuses–the University of Richmond included.

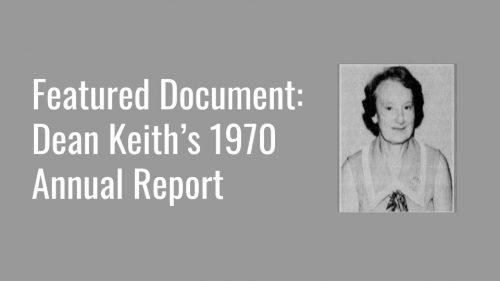

In 1970, the Westhampton College Dean of Students, Clara M. Keith, submitted an annual report on student life (available here) to the Dean of Westhampton College, Dr. Mary Louise Gehring, and President George Modlin for that school year.

This report was unique because there was a dramatic shift in Westhampton College student life with the administrators noting changes in the students’ lifestyle, attitude, and mood resulting in shifts in the “traditional boundaries of education.” Students were demanding autonomy in areas such as sex, drinking, parietal hours, and self-government.

For the next portion of the report, Dean Keith described some of the subcultures she had noticed: the change conformer, absurd plastic hippies, and the system dissenters.

She said, “system dissenters” were students who used “the dissent situation as a forum for (their) own inadequacies and is characterized by apathy, and sham rebelliousness.” They wanted immediate change and created chaos, and although there are only a few, “enough naive ones (could) be led along this path.”

We don’t know the names of these students. We don’t know what they did on campus, and how their acts of rebellion spurred changes in the quality of students’ lives. However, we do know that they made enough of an impact for the Dean of Students to dedicate the vast majority of her annual report to disparaging those engaging in dissent from the traditions and social norms of the University. And rather than responding to students seeking change with empathy, Dean Keith responded with a tone of contempt–completely dismissing the students by assuming that they were “acting out.”

To avoid jumping too far to conclusions, there’s an ample amount of information I don’t have about Dean Keith–like her intentions behind the rhetoric she used. However, that doesn’t negate the fact that the way she described her more radical students impacts how we see them today.

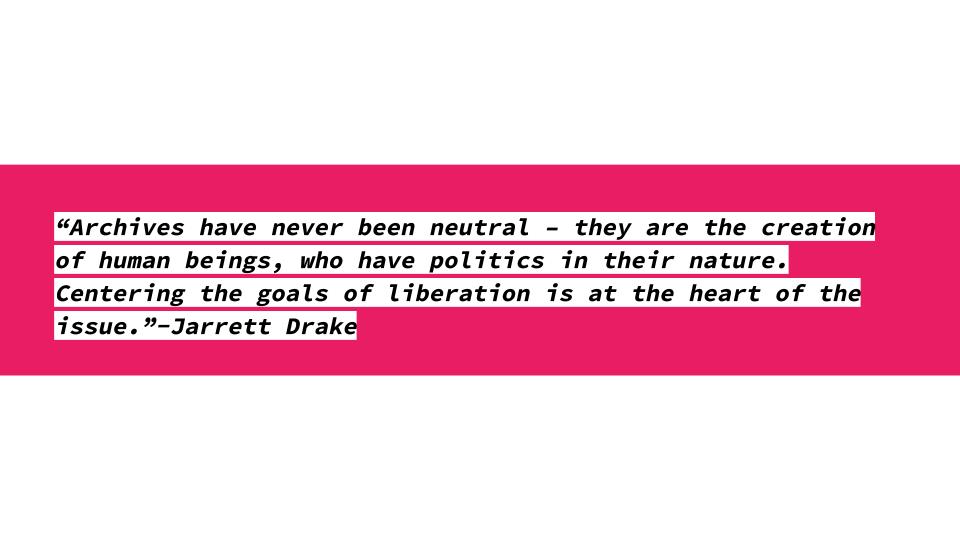

In reflecting on my work this summer I found a reading that we did in a group meeting, Jarrett Drake’s, “Documenting Dissent in the Contemporary College Archive: Finding our Function within the Liberal Arts,” to be the most influential.

Drake calls upon archivists to carve out space in the archive that demonstrates how our respective institutions have been opposed (to varying degrees) to “full liberation or independence”. At times, the University of Richmond was in direct opposition to their student’s increasing need to break free from oppressive traditions that elitism and sexism imposed upon their day to day lives. As an activist archivist, Jarrett Drake explained, the explicit function of liberal arts institutions isn’t to recreate systems of oppression, yet still, they continue to be guilty of doing so.

To me, I think that this project is attempting to reconcile with just that.

When I’ve attempted to explain what I was up to last summer, one question that really made me think was “That’s cool and all but what’s the point?” Being a humanities major, I’m used to folks downplaying the importance of engaging with ideas both past and present. But I’m thankful for the question because it really caused me to reflect on the work that my teammates and I had done. Most of the documents I worked with were constructed about 50 years ago so why are they still relevant?

The University of Richmond is completely different right? In 1968, UR admitted it’s first black student on its main campus. Three years ago, the University of Richmond hired its first black President. So yes, the University has seen a lot of change. However, working on this project has been a bit disheartening because I’ve also seen just how far we haven’t come. Minority students then, and minority students today are asking for some of the same changes: a more diverse and inclusive student body, and more faculty of color. Minority student both then and today are still trying to carve out spaces in an institution that wasn’t built with them in mind.

Dominant narratives like that of progress need to be challenged, especially now in the age of alternative facts. To much dismay, I’m not convinced that the majority of this country knows as much about where we have been, regarding our racial history, than they should.

For instance, perhaps if the country, as a whole, were more knowledgeable about the history of slavery and the Civil War and the ideologies in which they were grounded that persist today, we would be able to have more fruitful conversations about the place of confederate flags/statues in our communities

And so, perhaps if members of the University of Richmond community could actively engage with the truth of the past, we could have more fruitful conversations about how to make our campus community a more equitable place for everyone to thrive, not just survive. As a queer, black, woman at the University of Richmond, this project is relevant because it’s both cementing my story, and those who have come before me, unheard and unknown.

That’s the point.

The rebels that I mentioned in my example were the ones that were making necessary changes on our campus and for that, I believe they deserve their place, their independence, and their liberation. So, here’s to those, as Dean Keith described in her report, with their “wigs, beads, and perspiration stained Levis.” Here’s to the change conformers, the absurd plastic hippies, and the system dissenters. I think the world could use a bit more of them….especially now.

Thanks so much!