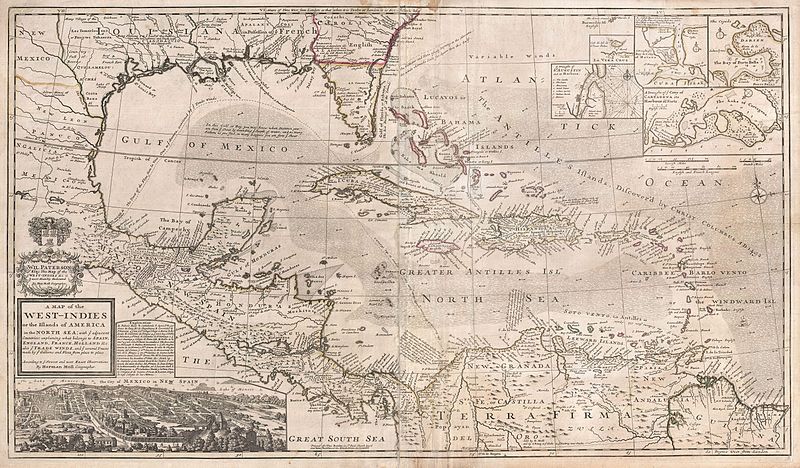

An ever reaching expansion of the European powers, the West-Indies hosted some of the most lucrative trade of its time. With England, France, Holland, Spain, and others vying for a share of the new world, cartography held a critical component in negotiation, investment, and politics. Even as Herman Moll’s 1732 map of the “Newest and most Exact Observations” came to fruition, thousands of ships navigated the Caribbean.¹ Notably tobacco, cotton, indigo, then eventually sugar gripped the agrarian markets of the many islands of the tropics. In fact, Moll’s map stems from the “golden age” of the Caribbean market, but from the later 18th century “silver age”.² Although Florida has yet to break its image of a fattened saw, we witness the power of information as European authorities flaunted it. The imperialism of the time shines through this map, and its existence is remnant of a great arms race among world powers.

Though clean and well produced, Moll’s work invokes a somewhat chaotic system of labeling and packing information into the map. From his cozy abode in London, Moll gained credibility from his ability to inscribe land claims, ports, routes, shoals, depths, currents, and winds in addition to the many established points of settlement. A well- forged relationship with explorer and pirate William Dampier largely produced the lexicon from which Moll worked. Without records from explorers like Dampier, Moll and other cartographers would not enjoy the information on which their maps rely. Even the common routes and tendencies of the Spanish treasure fleet appear for our viewing pleasure.³ Notably, some of the earliest chartings of the ocean itself manifest within this map. As this map’s publication coincides with Moll’s death, we might assume it is a culmination of his expertise.⁴ Drawing from years of artistic, scientific, and cultural energy, Moll reminds us that his profession integrates myriad finely tuned crafts—crafts applicable to any interests academic, economic, or political.

In his competence, we respect the emphases of the cartographer. Attention to motherlands marked by the only colored portions of the map display a clear variety of foreign interests. Remnant of a race to acquire distant lands, somewhat sporadic coverage reveals a tension between governments in a tightly knit realm. Sea travel necessitates frequent stops, and a preponderance of international interaction both might force governments together and apart. Thus, a special note must be made of Spain and England. Moll clearly devotes much of his carte blanche to information on the Spaniards. As the great rivalry of these nations dominated political affairs, Moll’s selection of detail likely caters to the interest in actionable intelligence on behalf of the British people. No British importer wants to run across the Armada at sea…but a pirate might! In fairness, the other nations of the Caribbean are also clearly marked, with a second magnitude of prevalence from much unloved France. One unconcealed aspect—European interest abroad was peaking, and definitive boundaries were in high contention.

Perhaps more intriguing than the map’s politics, Moll provides topographic, oceanographic and meteorologic data within his work. Although this visually pleases, these aspects provide important functionality on the page. Navigating an ocean riddled with shallows and sporadic islands creates barricaded waters with variable currents. Finding a path of least resistance then seems equally important as arriving at the proper destinations. After all, what might seem a circuitous route up the Florida coast presents a favorable route back to Europe rather than taking a direct, but dangerously rocky route through the Bahamas. In the nautical profession of the day, extra time at sea could mean spoiled goods or even dehydration. But on the other side, a well established route might also run traffic aside the Map’s favored ports and locations. Sea travel aside, terra firma hosts a wide array of mountains, rivers, cities, mines, and forts. With so much economic value at stake, most locations seem thoroughly vetted. Despite all the surrounding politics and nationalities, the region’s spirit remains a vivid picture abroad—a unified West-Indies.

This map not only reflects what Moll knew about the area, but it substantiates the European attitude toward interests abroad. Ultimately, this map is a trophy. The economic war games played by the Western world manifest themselves in the West-Indies. We glimpse the pride felt by territories abroad; and, stamped right next to the coat of arms, a dedication of all the information entailed as if the map was the key to world power.

¹- Moll, Herman. “A Map of the West-Indies.” Map. Wikimedia. Accessed September 23, 2014. http://commons.wikimedia.org.

²- S SMITH, “Sugar Trade: 17th-19th Centuries”. In Reader’s Guide to British History, edited by D. M. Loades. London: Routledge, 2003.

³- Hasty, William. “Piracy and the Production of Knowledge in the Travels of William Dampier, C.1679–1688.” Journal of Historical Geography 37, no. 1 (2011): 40-54. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2010.08.017.

⁴-“Herman Moll.” Geographicus. Accessed September 23, 2014. http://www.geographicus.com/mm5/cartographers/moll.txt.