The heroic figures of the Alabama civil rights movement are well known and rightly revered. Who can forget the stoic resilience of Rosa Parks, the brilliant rhetoric of Martin Luther King or the fearless tenacity of Fred Shuttlesworth? These ones were, after all, the faces of the movement, the ones who others rallied around, the people at the forefront. Heroes, however, come in all shapes and sizes and nowhere was this more evident than in the blistering streets of Birmingham in the summer of 1963. At that time, a generation of oppressed youngsters, some as young as five years of age, traded in their play-things and quietly said “enough”, taking their stand on the front-lines of a battle that was turning their state into a war zone.

By April of 1963, the campaign to desegregate the city of Birmingham was spluttering to a standstill. Support from local Black people was waning under threats that they would lose their jobs if they got involved. The imprisonment of Martin Luther King on April 12 did nothing to bolster support.  With it’s chairman behind bars, it was now up to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s (SCLC) director of direct action, James Bevel, to find a way to reinvigorate the campaign.

With it’s chairman behind bars, it was now up to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s (SCLC) director of direct action, James Bevel, to find a way to reinvigorate the campaign.

Bevel came up with a controversial strategy, one that King was, initially, opposed to. Get the children involved, Bevel urged. Children, he reasoned, were full of energy, they had no jobs to be threatened with losing and they were already organized and unified through their schooling. They were more teachable than their parents, more inclined to adopt the non-violent philosophy.

And so it was that on May 2nd, more than one thousand Black students skipped school and congregated at the 16th Street Baptist church ready to march downtown. Police Chief Eugene “Bull” Connor marshaled his forces against them. Coming out of the church in waves of 50, the students were arrested and carted off in police vans. Soon, however, there were no vans left and the police had to recruit school busses. Mahatma Gandhi’s non-violent goal of filling the jails was being realized.

The next day hundreds more children turned up at 16th Street Baptist, ready and willing to be carted off to jail. In fact, going to jail became a symbol of honor and pride, to the clear disgust of Bull Connor. Needing a trump card, Connor directed the police force and fire department to use force in order to put a stop to the marches.  By so doing, he was unwittingly playing into the SCLC’s hand. They knew that images of innocent children being pummeled by fire hoses and mauled by police dogs would force the nation to confront what Dr. King called “a crisis of conscience.”

By so doing, he was unwittingly playing into the SCLC’s hand. They knew that images of innocent children being pummeled by fire hoses and mauled by police dogs would force the nation to confront what Dr. King called “a crisis of conscience.”

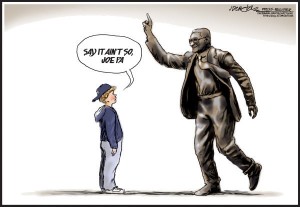

The images that captured the events of May 3rd and 4th did, indeed, shock not only the nation, but the entire world. There, in black and white, under screaming headlines, was undeniable proof of the racially fueled injustice that millions of Americans were suffering under day in and day out. But there, too, were images of young African-Americans standing proud. The cameras captured their dignity, their resolve and their courage. In contrast, the vitriol of the white crowds, the cold, clinical Gestapo-like efficiency of the Birmingham police department and the smirking, cigar crunching countenance of Bull Connor were also captured on film.

The contrast between good and evil was blatant and millions of people around the world were won over to the cause that the young people of Birmingham were championing. As a result national force was brought to bear on the issue of segregation. Although desegregation occurred slowly in Birmingham, the Children’s marches were a major factor in the national push towards the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibited racial discrimination in hiring practices and public services in the United States. And it was all thanks to the children.

– – – – – – – – – – –

About the author: Steve Theunissen is a history teacher and author. His new Young Adult novel “Through Angel’s Eyes” chronicles the historic events of the Birmingham campaign as seen through the eyes of a 13 year old black girl. Here is the trailer previewing the novel.

You can purchase “Through Angel’s Eyes” by clicking here.