By Dick Mercer

By Dick Mercer

The Chinese Chan (Zen) master Yunmen (c.860–949) was asked, “What are the teachings of a lifetime?” He replied, “An appropriate statement.”

Close to the end of Wu Cheng-en’s famous Ming dynasty novel Journey to the West (Hsi-yu Chi) the Buddhist monk Tripitaka and his four animal disciples–Monkey, Pigsy, Sandy–a dragon, and White Horse–are drawing close to India after a long, arduous, and dangerous journey from China. The reason for their quest is to receive Mahayana scriptures from the Buddha, Shakyamuni, and return to China with them.

Each animal member of this dharma posse has committed to the quest as a means of gaining freedom from punishment for the misuse of an extraordinary, superhuman power. Tripitaka, on the other hand, is no more than an ordinary Buddhist monk who has been given a very big job to do.

Having come a very long way, the Tang monk and his disciples, who fed on the wind and slept by the waters, one day find themselves before a tall mountain, yet another formidable obstacle to overcome.  Tripitaka says they must be cautious as there might be danger here; Monkey responds, “Master, you should relax and not worry.”

Tripitaka says they must be cautious as there might be danger here; Monkey responds, “Master, you should relax and not worry.”

What follows is a little argument about a very big Buddhist idea — prajnaparamita — the perfection of wisdom. It ends when both Tripitaka and Monkey fall silent. Pigsy collapses in laughter. Obviously Monkey doesn’t know what he’s talking about, but Tripitaka corrects Pigsy. Monkey’s silence is the true interpretation of prajnaparamita. In fact, one of his epithets is Aware of Vacuity — emptiness, a crucial part of the perfection of wisdom.

They move on. After crossing a wide river in a boat with no bottom, a paradoxical experience to be sure, the pilgrims are changed. Exhibiting a decorous self-control unusual for them, they meet the Buddha, Shakyamuni, and receive 35 major dharma works comprising over 5,000 scrolls. They set out on the journey back to China but before long a wind scatters all the scrolls on the ground. Opening one of them they discover “it was snowy white; there was not so much as half a letter on it.” In fact, all the scrolls are blank!

The posse returns to the Buddha who explains the blank scrolls are indeed the true scriptures, just as good as those with words, but because people are foolish and ignorant “there is nothing for it but to give them copies with some writing on.” The paradox of the truth of perfect wisdom is that it is wordless, but this is too hard for people who need language and must talk.

The implicit lesson is that it is more important to cultivate a negative capability — the patient, mindful toleration of uncertainty and paradox — and to carry on with equanimity than to hold on to the idea of scriptural truth that’s written down. Relax and don’t worry, as Monkey says.  So, freshly taught, the pilgrims set out again for China with the newly inscribed scrolls.

So, freshly taught, the pilgrims set out again for China with the newly inscribed scrolls.

Meanwhile Kuan-yin, reviewing a summary of the dharma posse’s quest, discovers the pilgrims must experience one more crisis, the 81st, before returning home. They find themselves stopped on the bank of a wide river they crossed on the way out to India. The great white turtle that ferried them across earlier offers to help them again, but when Tripitaka reveals he forgot to follow through on a promise he made to the turtle, they are all dumped in the water as the turtle submerges and swims away.

The pilgrims manage to save themselves and the scrolls. Tripitaka admits his careless mistake. He should have taken more care. Though they still have the scrolls, this fresh calamity makes clear that constant effort is required. There’s always something else. A hero’s work is never done.

They move on and are welcomed by friendly people they had earlier delivered from the terrible domination of a river demon. In gratitude for what the posse had accomplished for them, the people make statues of Tripitaka, Monkey, Pigsy, and Sandy. When the four view the figures they react with an unusual and charming humanity.

‘Yours is very like,’ said Pigsy nudging Monkey. ‘I think yours

is a wonderful likeness too,’ said Sandy to Pigsy, ‘but Master’s

really makes him out a little too handsome.’ ‘I think it’s very good,’

said Tripitaka.

It quickly becomes clear the people of the village have other honors ready for the pilgrims. That evening Tripitaka tells Monkey the villagers know they have mastered the secrets of the Way. We better creep away quickly he says, because “an adept does not reveal himself; if he reveals himself he is not an adept.” They all agree. Monkey controls his temper, Pigsy is no longer a fool, Sandy attains perfect discretion, Horse is well able to see the point of a discussion.

They move on. Returning to Chang-an, the imperial capital, they are received by the emperor himself. Monkey, Pigsy, Sandy attend the court despite their outlandish appearance. They behave. Tripitaka is seated next to the emperor and the scrolls are presented. That evening the pilgrims go the Tripitaka’s old temple for lodging.

Inside the temple, Pigsy did not shout for more food or create

any disturbance. Monkey and Sandy behaved with perfect

decorum. For all three were now illumined, and it cost them

no pains to stay quiet. When night came they all went to sleep.

All the pilgrims behave themselves with perfect mindfulness and self-control, qualities only recently acquired. The flaws that caused their original confinement and suffering have been reduced to nothing. They retain their powers, but they are now under control.

When morning comes the emperor reads a statement of thanks to Tripitaka for accomplishing his task. After settling on the disposition of the scrolls, Tripitaka is asked to do a reading from them on a platform in front of the pagoda that will house them.  The members of the dharma posse are attending him when he starts his recitation, but just as he begins, they are all miraculously lifted into the air and transported back to the presence of the Buddha in India where each is rewarded with an appropriate title. Perhaps best of all the terrible little migraine cap used to control Monkey when he gave in to bad temper and anger is removed. It is no longer necessary.

The members of the dharma posse are attending him when he starts his recitation, but just as he begins, they are all miraculously lifted into the air and transported back to the presence of the Buddha in India where each is rewarded with an appropriate title. Perhaps best of all the terrible little migraine cap used to control Monkey when he gave in to bad temper and anger is removed. It is no longer necessary.

The novel ends with a grand sense of accomplishment. The journey is done, the goal is realized, rewards are handed down, but the balance of power and behavior all the pilgrims now enjoy is the real reward and conclusion. This is a state of mind free of the suffering caused by the contamination of anger, sensuality, carelessness, upsetting emotional attachment, short-sightedness, and other untransformed human weaknesses.

Certainly their journey is finished, but the lesson implicit in the circular, wandering movement of the quest and the oddly conceived requirement of another calamity, the 81st, is one of non-attainment.

In this view enlightenment is a continual process of coming to terms with oneself, of overcoming flaws. Monkey’s original vision of the hero as a winner-take-all kind of strong guy is replaced by the idea of constantly repairing the disorder of the mind. This isn’t done by any final achievement, though he achieves it. This is a paradoxical conclusion like the mutual silence that ends the discussion between Tripitaka and Monkey about prajnaparamita — the perfection of wisdom.

Perhaps the sense of closure the novel ends with is an illustration of just what the Buddha, Shakyamuni, means when he says the blank scrolls, the empty scrolls, are the true scriptures, but people are too foolish and ignorant to realize this and they need something to hold on to.

The real issue, however, is one of behavior, not words. Left unstated at the end is that the end isn’t an end; the end is, indeed, a process of constantly maintaining mental focus and taming one’s monkey mind — making the appropriate response in the face of unending — often unexpected — change.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

This essay is Richard Mercer’s fifth analysis of heroism from the Buddhist perspective. His first essay focused on the Bodhisattva. Mercer has been a Visiting Instructor of English and Core (especially Edgar Allan Poe and Samuel Beckett) at the University of Richmond. He has studied Buddhism since the early 1990s. Only recently has he realized that the Bodhisattva ideal is a wonderful and practicable model to follow.

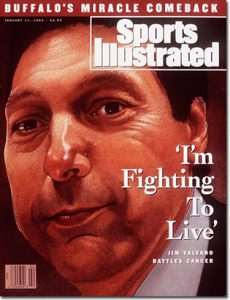

By Meghan Dillon

By Meghan Dillon Jimmy V could live out his aspirations. One of the many reasons I see Jimmy V as a hero is that, along the way to accomplishing his dream of winning a national championship, he took on a personal ideology of living that would allow him, a seemingly ordinary man, accomplish things that we see as extraordinary. This ideology would help him to innumerable victories.

Jimmy V could live out his aspirations. One of the many reasons I see Jimmy V as a hero is that, along the way to accomplishing his dream of winning a national championship, he took on a personal ideology of living that would allow him, a seemingly ordinary man, accomplish things that we see as extraordinary. This ideology would help him to innumerable victories. By Dick Mercer

By Dick Mercer The story of Hsuan-tsang is very different. An orphan found floating in a basket down a river, he is taken in and raised as a Monk at Hung-Fu Buddhist temple in the imperial capital Ch’ang-an. As was the case with the Jade Emperor of heaven struggling with Monkey, the mortal Tang emperor is embroiled in troubles that literally take him to hell and back burdened with a heavy obligation to sponsor a grand religious ceremony. He selects Hsuan-tsang to celebrate these rites.

The story of Hsuan-tsang is very different. An orphan found floating in a basket down a river, he is taken in and raised as a Monk at Hung-Fu Buddhist temple in the imperial capital Ch’ang-an. As was the case with the Jade Emperor of heaven struggling with Monkey, the mortal Tang emperor is embroiled in troubles that literally take him to hell and back burdened with a heavy obligation to sponsor a grand religious ceremony. He selects Hsuan-tsang to celebrate these rites. Kuan-Yin to join the pilgrimage in exchange for freedom from bondage. It soon is obvious to the new members, however, that Monkey is by far the most powerful member of the group. In fact, Pigsy asks Monkey why doesn’t he simply carry them all to India in an instant and so avoid all the hard work and dangers that surely lie in front of them.

Kuan-Yin to join the pilgrimage in exchange for freedom from bondage. It soon is obvious to the new members, however, that Monkey is by far the most powerful member of the group. In fact, Pigsy asks Monkey why doesn’t he simply carry them all to India in an instant and so avoid all the hard work and dangers that surely lie in front of them. By

By  But Jack Ormes was a Black woman who aspired to make a career for herself in journalism and cartooning, two fields divided along lines of skin color and sex. She crossed those lines and erased them by becoming the first Black woman in America to produce a nationally syndicated comic strip. The strip starred a popular character named Torchy, who was a well-educated and independent Black woman, very different from most contemporaneous depictions of Blacks. According to the 1953 documentary One Tenth Of A Nation, Ormes’ comics were seen in scores of newspapers and she had an audience of over a million readers. The effect of her work on a country on the verge of a Civil Rights revolution cannot be underestimated.

But Jack Ormes was a Black woman who aspired to make a career for herself in journalism and cartooning, two fields divided along lines of skin color and sex. She crossed those lines and erased them by becoming the first Black woman in America to produce a nationally syndicated comic strip. The strip starred a popular character named Torchy, who was a well-educated and independent Black woman, very different from most contemporaneous depictions of Blacks. According to the 1953 documentary One Tenth Of A Nation, Ormes’ comics were seen in scores of newspapers and she had an audience of over a million readers. The effect of her work on a country on the verge of a Civil Rights revolution cannot be underestimated.