By Kathryn Lynch

By Kathryn Lynch

Human connections are a fickle and funny thing. Throughout our lifetimes we may pass by thousands of people without giving a second thought to who they are or where they’re going. Yet one simple interaction can completely alter the course of someone’s life. We only have to pay attention.

Chen Si of Nanjing, China is an ordinary man of simple means. In 2003, he was barely able to make a living selling vegetables in a downtown market. It was then he began his daily walk down the Nanjing Yangtze River bridge, the most popular site for suicides on record. China has more deaths by suicide than any other country in the world, at over 280,000 a year — twice the rate of the United States. The first day in 2003 he saved a man’s life after grabbing him from the railing and tackling him to the ground.

After that event, Si took it upon himself to serve as guardian angel to those who wished to end their lives on the bridge. He built a small house next to the entrance to the bridge, where he has lived alone for the past 11 years. Each year Si saves an estimated 144 people.

Throughout his service, he has seen people with problems of all kinds, but all are plagued by the same inescapable pain and hopelessness.  According to Si, “I know they are tired of living here. They have had difficulties. They have no one to help them.”

According to Si, “I know they are tired of living here. They have had difficulties. They have no one to help them.”

But Chen Si’s heroism goes beyond the physical act of saving one’s life. He provides salvation. He gives hope and direction where there is none. One story he remembers is of a woman whose abusive husband left her and her 3-month old child with nothing. She had no education, no job, and no means of caring for the child. She hoped that her death would require her husband to take care of her baby. After convincing her to leave the bridge with him, Si tracked him down and brought his wife and child with him. After the husband spit in his face, Si responded, “I am her brother now. If you ever hurt her again, I am not going to let you get away with it.” The couple left, and Chen hasn’t heard from them again.

There have been countless others. The billionaire who lost everything. The student who couldn’t handle failure. The dreamer who bet it all and lost in the big city. Si has talked to all of them. And while he cannot alter the circumstances that bring them to that point, he feels it is his responsibility to try and put them on a better path. “I always have to tell them there is nothing I can’t solve,” Chen said. “It’s a lie. Yet I have to keep on telling the lie, to make them think things will get better.”

Chen Si teaches us that those at their lowest point in life, those who are so lost that they feel that they will never find their way again, are in the most need of our help. Many of the people on that bridge did not want Chen Si’s kind words and strong hands to pull them back from the edge —  they pushed him away and yelled in his face, content to accept their fate, and did not believe they were worthy of help and compassion.

they pushed him away and yelled in his face, content to accept their fate, and did not believe they were worthy of help and compassion.

It is easy to be a hero where there is a hole to fill, where people actively look for someone to protect and care for them and give their love in return. Chen Si’s true heroism lies in his ability to look for those who do not advertise their struggle. Those who have given up hope that a hero will ever appear. Many of us in a similar situation would wonder how to address such a problem of this magnitude, how to save people who have no desire to be saved.

To Chen Si, there is no choice or considerations to make. “There is a saying in China,” he says, “the prosperity of a nation is everyone’s responsibility. How can we all avoid this responsibility?”

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Kathryn Lynch is an undergraduate enrolled in Scott Allison’s Heroes and Villains First-Year Seminar at the University of Richmond. She composed this essay as part of her course requirement. Kathryn and her classmates are contributing authors to the forthcoming book, Heroes of Richmond, Virginia: Four Centuries of Courage, Dignity, and Virtue.

By Rick Hutchins

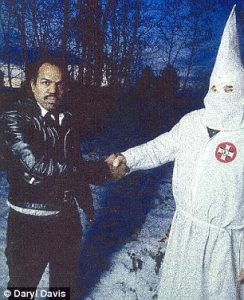

By Rick Hutchins bachelor’s degree in music and who has performed with artists such as Chuck Berry and Jerry Lee Lewis (to say nothing of his own band), is a Black man who was a child during the Civil Rights Era. He experienced firsthand the harsh reality of that struggle when he became the first Black member of a local Cub Scout troop in Massachusetts. But his innate intellectual curiosity combined with his benevolent disposition to form a most unique reaction to the problem of racism.

bachelor’s degree in music and who has performed with artists such as Chuck Berry and Jerry Lee Lewis (to say nothing of his own band), is a Black man who was a child during the Civil Rights Era. He experienced firsthand the harsh reality of that struggle when he became the first Black member of a local Cub Scout troop in Massachusetts. But his innate intellectual curiosity combined with his benevolent disposition to form a most unique reaction to the problem of racism. Davis is currently in possession of more than two dozen KKK robes, given to him by former Klansman who have abandoned their ideology, disarmed by the mere existence of this good-natured peacemaker. Among those who have foresworn White supremacy in favor of a Black friend is Roger Kelly, former Imperial Wizard of the Maryland KKK. Kelly later invited Davis to be his daughter’s godfather.

Davis is currently in possession of more than two dozen KKK robes, given to him by former Klansman who have abandoned their ideology, disarmed by the mere existence of this good-natured peacemaker. Among those who have foresworn White supremacy in favor of a Black friend is Roger Kelly, former Imperial Wizard of the Maryland KKK. Kelly later invited Davis to be his daughter’s godfather. By

By  But Jack Ormes was a Black woman who aspired to make a career for herself in journalism and cartooning, two fields divided along lines of skin color and sex. She crossed those lines and erased them by becoming the first Black woman in America to produce a nationally syndicated comic strip. The strip starred a popular character named Torchy, who was a well-educated and independent Black woman, very different from most contemporaneous depictions of Blacks. According to the 1953 documentary One Tenth Of A Nation, Ormes’ comics were seen in scores of newspapers and she had an audience of over a million readers. The effect of her work on a country on the verge of a Civil Rights revolution cannot be underestimated.

But Jack Ormes was a Black woman who aspired to make a career for herself in journalism and cartooning, two fields divided along lines of skin color and sex. She crossed those lines and erased them by becoming the first Black woman in America to produce a nationally syndicated comic strip. The strip starred a popular character named Torchy, who was a well-educated and independent Black woman, very different from most contemporaneous depictions of Blacks. According to the 1953 documentary One Tenth Of A Nation, Ormes’ comics were seen in scores of newspapers and she had an audience of over a million readers. The effect of her work on a country on the verge of a Civil Rights revolution cannot be underestimated.