By J. A. Schultz

By J. A. Schultz

Movies aren’t history.

That goes almost without saying. Very different skills are needed between recording something for posterity and bringing a rousing tale to the screen. And as such what is shown to an audience should always be taken with a grain of salt. Facts can be altered for the cause of entertainment. Events can change, sometimes beyond recognition, for the sake of the plot.

However, movies should not be dismissed completely out of hand. For while they are not an accurate recording of history they are in fact preserved moments in time. What film and television record are how people (the writers and the audience they were made for) perceived the world around them. What made the hero? What made the villain?

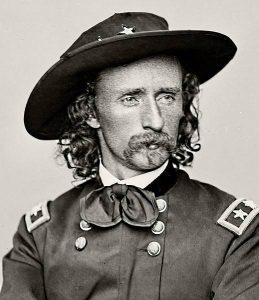

A good example of the intersection of fact and fiction is the life of General George Armstrong Custer.

The Custer of history, the man of flesh and blood, is best known for the worst day of his life: the Battle of Little Big Horn when the 7th Cavalry met the united tribes of Lakota Sioux and Cheyenne. Custer and his regiment would not survive but odd, at times nearly unrecognizable, doppelgangers would be born from that moment of time. Doppelgangers that continue to exist to this day.

The first of those fictional creations actually occurred within a few short years after the battle, though not yet on film. “Buffalo” Bill Cody incorporated the event in his wild west show, that for a while even starred Custer’s lifetime nemesis, Chief Sitting Bull. The show portrayed what would become the familiar tale of Custer: the noble warrior valiantly fighting a hopeless battle against impossible odds.

event in his wild west show, that for a while even starred Custer’s lifetime nemesis, Chief Sitting Bull. The show portrayed what would become the familiar tale of Custer: the noble warrior valiantly fighting a hopeless battle against impossible odds.

It wasn’t long before the story told before a live audience found its way to the burgeoning medium of film. Custer the hero would make his way into films like The Santa Fe Trail (1940), They Died With Their Boots On (1941), 7th Cavalry (1956), and much later in TV series like Cheyenne (Season 4 episodes “Gold, Glory, and Custer”). The man standing on the hill, surrounded by enemies and betrayed by allies, making his last stand. It would become the version of Custer that most people would become familiar with, whether they agreed with it or not.

Yet oddly this wouldn’t be the only doppelganger to come to life in the realm of the screen.

The first embryonic version of a less noble Custer came in the form of Lieutenant Colonel Owen Thursday in the 1948 film Fort Apache. While not actually playing Custer, actor Henry Fonda portrays a character whose overconfidence and arrogance eventually leads his command into a massacre very much like that of Little Big Horn. But the full iteration of this new Custer would come in later films like Little Big Man (1970), The French/Italian farce Don’t Touch the White Woman! (1974), the alternately-historical The Court Martial of George Armstrong Custer (1977), and A Night at the Museum: Battle for the Smithsonian (2009). Custer was now a bumbling fool at best or a murderously insane madman at worst. The nadir of this version of Custer came in the 1990s TV series Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman where Custer was a brutal sadist who was a threat to friend and enemy alike. Custer the Hero still exists but now he has to share space with Custer the Villain and Custer the Buffoon.

Yet these doppelgangers — the noble hero and the bumbling killer — actually say more about us, the writers and the audience, than the real man. In the time since Little Big Horn society has changed. Attitudes towards Native Americans, tastes in entertainment, and the  tendency to deconstruct heroes rather than build them all conspire to change how we view historical figures. It’s no longer popular to portray a General of an aggressive, expanding power — as the United States was in the 1800s — as a heroic figure (and even that sentence alone could likely cause heated debate).

tendency to deconstruct heroes rather than build them all conspire to change how we view historical figures. It’s no longer popular to portray a General of an aggressive, expanding power — as the United States was in the 1800s — as a heroic figure (and even that sentence alone could likely cause heated debate).

And this is why movies and television are important when it comes to understanding heroes. They are our collective unconscious where our dreams and fears are given form. Our concepts of morality and nobility are played out. Frozen moments, like insects trapped in amber, that tell us what the world was like when they were made. They tell us what was important to those making them whether we agree with them or not. Modern sensibilities cannot alter them. Films and television may be suppressed, “re-imagined”, or edited but something of the tales will remain. We may not always like what we see in these shadows on screen but it is important that we see them for what they are and learn from them.

And maybe be aware of what we’re leaving behind, for today’s on-screen heroes can become tomorrow’s villains.

– – – – – – – – – – – – –

The author, Jesse Schultz, is looking forward to seeing the fictionalized versions of his life.