By Scott T. Allison

By Scott T. Allison

This blog post is excerpted from:

Allison, S. T. (2019). Heroic consciousness. Heroism Science, 4, 1-43.

The philosopher Yuval Noah Harari (2018) recently described consciousness as “the greatest mystery in the universe”.

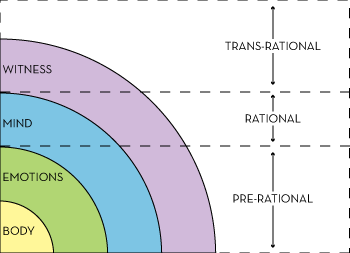

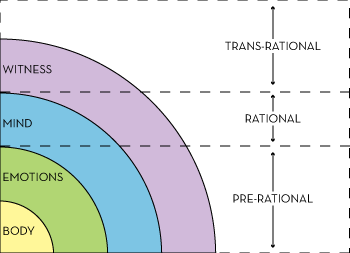

What exactly is heroic consciousness? It is a way of seeing the world, perceiving reality, and making decisions that lead to heroic behavior. Human beings display heroic consciousness by employing the nondualistic strategy of unifying disparate experiences into integrated wholes, by engaging in an enlightened processing of transrational phenomena, and by acquiring the wisdom to know when, how, and whether to act heroically.

Heroic consciousness is to be aware of thoughts, use them judiciously, but not be obsessively driven by them. It is to have an ego but not be a slave to it. It is to know when heroic action is needed and when it is not.

I have identified four telltale signs that an individual has experienced heroic consciousness. The four characteristics of the hero’s consciousness include the tendency to show clarity and effectiveness in: (1) seeing the world from a nondualistic perspective; (2) processing transrational phenomena; (3) exhibiting a unitive consciousness; and (4) demonstrating the wisdom to know when to act heroically and when not to act when action would be harmful.

1. Nondualistic Thinking

A central element of heroic consciousness is the hero’s use of the mental and spiritual approach to life known as nondualistic thinking (Jones, 2019; Loy, 1997; Rohr, 2009). Heroes are adept at both dualistic and nondualistic mental approaches. Heroes first master dualistic thinking, the ability  to partition and label the world when necessary, and then they learn to go beyond this binary thinking by seeing a rich, nuanced reality that defies simple mental compartmentalizations.

to partition and label the world when necessary, and then they learn to go beyond this binary thinking by seeing a rich, nuanced reality that defies simple mental compartmentalizations.

Cynthia Bourgeault (2013) describes this richer psychological mindset as third force thinking that transcends the rigid mindset of dualities. A third force solution to a problem is “an independent force, coequal with the other two, not a product of the first two as in the classic Hegelian thesis, antithesis, synthesis” (p. 26).

Psychologists have known for a half-century that human cognition is characterized by a need to simplify and categorize stimuli (Fiske & Taylor, 2013). Because our lives include daily encounters with a range of phenomena that defy simple dualistic thinking, it is of crucial importance that we engage in third force approaches that access our deeper intuitions and artistic sensibilities.

Third force solutions to problems are innovative and heroic solutions. In my view, it is crucial that we emphasize third force nondualistic thinking approaches in early education to help promote heroic mindsets in young children.

In contrast to dualistic thinking, nondualistic thinking resists a simple definition. It sees subtleties, exceptions, mystery, and a bigger picture. Nondualistic thinking refers to a broader, dynamic, imaginative, and more mature contemplation of perceived events (Rohr, 2009). A nondualistic approach to understanding reality is open and patient with mystery and ambiguity. Nondualistic thinkers see reality clearly because they do not allow their prior beliefs, expectations, and biases to affect their conscious perception of events and encounters with people.

Abraham Heschel (1955) described it as the ability to let the world come at us rather than us come at the world with preconceived categories that can skew our perceptions. “Our goal should be to live life in radical amazement,” wrote Heschel. “Wonder or radical amazement, the state of maladjustment to words and notions, is therefore a prerequisite for an authentic awareness of that which is” (p. 46-47, italics added).

Rohr (2009) describes nondualistic thinking as “calm, ego-less seeing” and “the ability to keep you heart and mind spaces open long enough to see other hidden material” (p. 33-34).  According to Rohr, this type of insight occurs whenever “by some wondrous coincidence, our heart space and mind space, and our body awareness are all simultaneously open and nonresistant” (p. 28).

According to Rohr, this type of insight occurs whenever “by some wondrous coincidence, our heart space and mind space, and our body awareness are all simultaneously open and nonresistant” (p. 28).

Asian spiritual philosophies describe nondualistic seeing as the third eye, which is the enlightened ability to see the world with balance, wisdom, and clarity. Heroic protagonists in literature are often compelled to view the world at these deeper levels by traversing the hero’s journey, which involves a descent into a desperately challenging and painful situation. During these darkest of times, heroes realize that their simple dualistic mindsets no longer work for them.

The pre-heroic consciousness must be discarded, allowing heroes to achieve clarity and accumulate life-changing insights about themselves and the world (Allison & Goethals, 2014). We are all called to experience a transformative, expansive, nondualistic consciousness, and we usually get there through great love (Rohr, 2011) or great suffering (Allison & Setterberg, 2016).

But not everyone gets there. Some remain sadly stuck at the level of dualistic consciousness. Dualistic thinkers have a split consciousness that contributes to perpetuating all the damaging “isms” of society – racism, sexism, classism, ageism, and nationalism, to name a few. Split people tend to split people.

If nondualistic thinking reflects a more heroic consciousness than dualistic thinking, how does one adopt a nondualistic approach to the world? I believe there are at least two routes to attaining nondualistic thought. One route consists of Abraham Heschel’s idea of approaching the world with an openness and receptivity to awe, wonder, and gratitude (Burhans, 2016). Heschel called this radical amazement. Our thoughts constrict what we can see, according to Heschel (1955, p. 47): “While any act of perception or cognition has as its object a selected segment of reality, radical amazement refers to all of reality”.

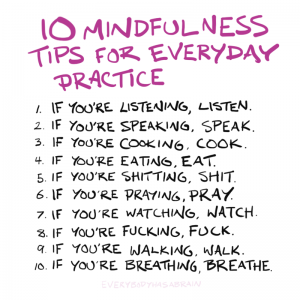

Research shows that training in mindful meditation can help quell the initial labeling and categorizing process and thus better enable people to see the world as it is rather than as we “think” it is (Jones, 2019). In his book Blink, Malcom Gladwell (2007) argues that spending less time thinking and relying upon one’s immediate intuitions often engenders greater clarity about the world.

This first route to nondualistic thinking requires us to adopt practices that encourage us to approach the world with more wonder, awe, openness, intuition, feeling, and artistic sensibility. Adopting these practices inhibits our predilection for forming quick mental partitions of the world that limit our ability to see the world more broadly, deeply, holistically, heroically, and with more radical amazement.

The second route to nondualistic thinking does not seek to reduce initial mental labeling but instead focuses on correcting for mental labels after they have already been generated. There is some evidence that the tendency to make quick, spontaneous categorizations of the world is wired into us and may therefore be very difficult to avoid (Pendry & Macrae, 1996).

Awareness of this pattern is critical to remedying it. If we find ourselves dividing the world dualistically in our minds, we can become aware of this initial binary thinking and then pause to make the necessary corrections. Engaging in mental adjustments that help us see the world in broader, more unifying terms may indeed be the height of heroic consciousness.

This two-step process of automatic judging and then correcting has been documented as a pervasive human decision-making process (e.g., Gilbert, 1998; Kraft-Todd & Rand, 2017; Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). We are all capable of heroic consciousness even if at first, as a result of deeply ingrained habit, we show a dualistic pre-heroic consciousness. The challenge here is ensuring that we make the full correction. Research shows that people tend to make initial, faulty judgments and then fail to sufficiently correct for them (Fiske & Taylor, 2013). The heightened awareness of a heroically conscious individual will not allow this to happen.

There are many historical examples of the heroic use of nondualistic consciousness. John F. Kennedy used nondual thinking in his response to the Cuban missile crisis in 1962. A year earlier, Kennedy and his advisors were humiliated by the consequences of their dualistic reaction to the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba. Learning from this failure, Kennedy patiently considered many possible responses to the missile crisis rather than frame the decision as either going to war versus doing nothing. He settled on a naval military blockade that nicely diffused the crisis and averted a nuclear showdown with the Soviets.

Mahatma Gandhi’s use of nonviolent, passive resistance is another striking example of nondualistic thinking. Rather than frame India’s struggle for independence as either a violent revolution or total submission, Gandhi developed an ingenious strategy of peaceful resistance that became a model for social change worldwide.

Martin Luther King, Jr. practiced this same nondualistic approach during the U.S. civil rights movement of the 1960s. “Nonviolent resistance,” King wrote, is “a courageous confrontation of evil by the power of love” (King, 1958). Through patience, contemplation, and openness, a third-force solution to problems emerges that reflects a higher intelligence and consciousness.

2. Processing of Transrational Phenomena

Encounters with experiences that defy rational, logical analysis are an inescapable part of life. A second major characteristic of the hero’s consciousness is the ability to process and understand these experiences, as they often reflect the most important issues of human existence. These transrational phenomena are mysterious and challenging for most people to fathom, and thus they require a heroic consciousness to unlock their secrets.

Rohr (2009) has identified five transrational phenomena, and I will add two more. Rohr’s five are love, death, suffering, God, and eternity. The two that I am adding are paradox and metaphor (see also Allison & Goethals, 2014;  Efthimiou, Bennett, & Allison, 2019). These seven transrational experiences are a ubiquitous part of human life, pervade good hero mythology and storytelling, and are endemic to the classic monomythic hero’s journey as described by Joseph Campbell (1949).

Efthimiou, Bennett, & Allison, 2019). These seven transrational experiences are a ubiquitous part of human life, pervade good hero mythology and storytelling, and are endemic to the classic monomythic hero’s journey as described by Joseph Campbell (1949).

To illustrate the importance of understanding the seven transrational experiences in storytelling, let us consider the role of each in the classic 1993 film Groundhog Day starring Bill Murray. The movie can be summarized as follows: The hero, Phil Connors, is a narcissistic television meteorologist covering the annual Groundhog Day ritual in Pennsylvania. Phil is hateful to everyone and has a crush on his producer, Rita. Soon he discovers that each day is a repetition of the previous day, and no one but him is aware that the day is repeating itself. The movie derives much of its humor and wisdom from how Phil handles his temporal entrapment.

Here’s how the seven transrational phenomena of the hero’s journey come into play:

(1) Eternity: The hero of Groundhog Day, Phil Connors, finds himself stuck in time, repeating the same day over and over again, seemingly for eternity.

(2) Suffering: Phil suffers greatly because he cannot escape the time trap. He suffers also because despite his best efforts he cannot win the heart of Rita, his producer.

(3) God: Although never mentioned as divine per se, some outside authority or supernatural force is responsible for entrapping Phil in the time loop. This mysterious power is also responsible for eventually releasing Phil from the time loop.

(4) Love: Phil is deeply in love with Rita, but it is not until the end of the story that she reciprocates his affections.

(5) Death: Unable to win Rita’s heart or escape the time trap, Phil ends his own life many times and in many ways, only to discover that suicide for him is impossible. Later, he is unable to prevent a homeless man from dying.

(6) Metaphor: The endlessly repeating day is a metaphor for the rut of unhappy living that plagues most of humanity.

(7) Paradox: Phil has to suffer to get well. The harder Phil tries to win Rita’s heart, the less successful he is. The more he focuses on changing himself, the more he changes Rita. By helping others, he helps himself.

When we are young and not far along our hero’s journeys, all seven of these transrational experiences tend to overwhelm our ill-equipped pre-heroic consciousness. We need stories like Groundhog Day to help us awaken to a new, wiser, broader consciousness. Much like Phil Connors, most human beings suffer until and unless they adopt a heroic consciousness that enables them to grasp the transrational world.

Heroic consciousness is available to us once we realize that choosing to remain unconscious leaves us feeling alone, disconnected, frustrated, and miserable. I am not arguing that our pre-heroic rational minds are bad; in fact, pre-heroic consciousness is useful for healthy early life ego development and identity formation. Phil Connors became a successful television meteorologist by relying on his pre-heroic consciousness alone. I am only claiming that pre-heroic consciousness is insufficient for mastering life’s biggest mysteries involving the seven transrational phenomena. These issues require a broader, more enlightened consciousness to understand, and until we understand them, we are doomed to suffer much like Phil Connors.

We need both dualistic and nondualistic approaches to navigate our world successfully. To be the master of both worlds, as Joseph Campbell (1949) phrased it, we must first master dualistic thinking as our friend Phil Connors did in becoming a successful meterologist. This success alone will not bring happiness. To escape the trap of this first world, we must master nondualistic approaches toward understanding and successfully navigating through the mysteries of the transrational world.

3. Unitive Consciousness

“A human being is a part of the whole, called by us ‘Universe,’ a part limited in time and space. He experiences himself, his thoughts and feelings as something separated from the rest — a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. This delusion is a kind of prison for us, restricting us to our personal desires and to affection for a few persons nearest to us. Our task must be to free ourselves from this prison by widening our circle of compassion to embrace all living creatures and the whole of nature in its beauty.” — Albert Einstein (1950)

Heroic consciousness is a nondual, unitive consciousness, exactly like that described in the above quote by Einstein (1950). While recognizing and valuing individual separateness and multiplicity, heroic consciousness sees and seeks unification.

Joseph Campbell (1988) enjoyed telling the story about two Hawaiian police officers who were called to save the life of a man about to jump to his death. As the man began to jump, one officer grabbed onto him and was himself being pulled over the ledge along with the man he was trying to save.  The other officer grabbed his partner and was able to bring both men back to safety. Campbell explained the first officer’s self-sacrificial behavior as reflecting “a metaphysical realization which is that you and that other are one, that you are two aspects of the one life” (p. 138).

The other officer grabbed his partner and was able to bring both men back to safety. Campbell explained the first officer’s self-sacrificial behavior as reflecting “a metaphysical realization which is that you and that other are one, that you are two aspects of the one life” (p. 138).

Heroic consciousness is the awareness of this truth. Campbell (1988) taught us that the classic, mythic initiation journey ends with the hero discovering that “our true reality is in our identity and unity with all life” (p. 138).

Einstein’s metaphor of the mental prison is especially descriptive of pre-heroic consciousness. The pre-hero is trapped in the “delusion” of tribal identity and of separateness from the world. Consistent with the mental prison metaphor, spiritual leaders have referred to our over-reliance on mental life as an “addiction” (Rohr, 2011) and a “parasitic” relationship (Tolle, 2005). Both the perseverance effect and confirmation bias in psychology refer to the troublesome tendency of people to hold onto their beliefs even when those beliefs have been discredited by objective evidence (Fiske & Taylor, 2013).

The stories that we tell ourselves and cling to can hinder the development of our heroic consciousness (Harari, 2018). This is why hero training programs focus on strategies aimed at re-writing our mental scripts to bolster our heroic efficacy (Kohen et al., 2017). The trait of being open to new ways of thinking is considered by psychologists to be a central characteristic of healthy individuals (Hogan et al., 2012).

Heroes escape their mental prisons and experience a transformed consciousness when they engage in the process of self-expansiveness (Friedman, 2017), during which the boundaries between oneself and others are perceived as permeable. Many spiritual geniuses, including Thich Nhat Hanh, Eckhart Tolle, and Richard Rohr, deem unitive consciousness as core to their definition of spiritual maturity.

Buddhist philosopher Hanh (1999) writes that human beings tend to believe that their fellow humans “exist outside us as separate entities, but these objects of our perception are us …. When we hate someone, we also hate ourselves” (p. 81). Rohr (2019) emphasizes that consciousness is the key to understanding the oneness of humanity: “The old joke about the mystic who walks up to the hotdog vendor and says, ‘Make me one with everything,’ misses the point. I am already one with everything. All that is absent is awareness” (p. 1).

In their list of features that distinguish heroes from villains, Allison and Smith (2015) argued that heroes seek to unite the world whereas villains seek to divide it. Unification in perception and in action tends to reduce human suffering, whereas division in perception and in action tends to produce suffering. The hero’s consciousness thus operates in the service of ending human suffering, and the villain’s consciousness (and also at times pre-heroic consciousness) can operate in the service of producing human suffering.

Heroic consciousness is therefore necessary to achieve personal wholeness, collective wholeness, and the future well-being of our planet.

4. Wisdom of Tempered Empowerment

In the 1930s, a theologian and philosopher named Reinhold Niebuhr penned what is today commonly referred to as the serenity prayer (Shapiro, 2014). The prayer is as follows:

God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change,

Courage to change the things I can,

And wisdom to know the difference.

The serenity prayer has enjoyed considerable worldwide recognition as a result of being adopted by nearly every 12-step recovery program. I believe the serenity prayer contains brilliant insight about heroic, behavioral self-regulation.

George Goethals and I have written elsewhere about addiction recovery programs deriving their effectiveness from their use of the hero’s journey as a blueprint for growth and healing (Allison & Goethals, 2014, 2016, 2017). Other scholars and healers have also noted the parallel between heroism and addiction recovery work (Efthimiou et al., 2018; Furey, 2017; Morgan, 2014). The serenity prayer is the centerpiece of recovery programs because addiction is largely a disease of control (Alanon Family Groups, 2008). The prayer works because it helps recovering addicts develop the wisdom to know when to exercise control over their lives and when to admit powerlessness.

Each of the three lines of the serenity prayer reflects the wisdom of heroic consciousness. First, the prayer asks for the serenity to accept people and circumstances that cannot be changed. This is a prayer for acceptance of non-action when action is pointless. It takes a deeper, broader, heroic consciousness to recognize the futility of action in a situation that seems to call for action.

For example, if a chronic alcoholic is repeatedly arrested for disorderly conduct, and their partner repeatedly bails him out of jail, the partner may finally have had enough and decide not to bail out the alcoholic in the future. Not helping someone may at times lead to a better outcome than helping someone.  After not being bailed out, the alcoholic sitting in jail may do some much-needed soul-searching that can lead to their own recovery and healing. The partner who fails to help the jailed alcoholic may be more of a hero by doing nothing than by any action they can take. In terms of the serenity prayer, the partner accepts that they cannot change the alcoholic and that they cannot stop the cycle of repeated arrests for disorderly conduct. Passive acceptance and non-action are sometimes the wisest responses and reflect a nondualistic heroic consciousness.

After not being bailed out, the alcoholic sitting in jail may do some much-needed soul-searching that can lead to their own recovery and healing. The partner who fails to help the jailed alcoholic may be more of a hero by doing nothing than by any action they can take. In terms of the serenity prayer, the partner accepts that they cannot change the alcoholic and that they cannot stop the cycle of repeated arrests for disorderly conduct. Passive acceptance and non-action are sometimes the wisest responses and reflect a nondualistic heroic consciousness.

Beggan (2019) would call this heroic non-action an example of meta-heroism. According to Beggan, “The meta-hero acts heroically by not acting heroically, at least in terms of a more narrow definition of heroic action. In this case, the right thing may actually create hardship and moral ambiguity” (p. 13).

Beggan (2019) points out that there is a bias in heroism science toward taking action rather than inaction. His analysis puts the adage that “the opposite of a hero is a bystander” on its head. It seems there are times when heroes are indeed bystanders. But it takes an enlightened consciousness to discern these moments that call for heroic inaction.

The second element of the serenity prayer focuses on praying for the courage to change things that are changeable. After realizing that they are powerless over the alcoholic, the partner may recognize that they do have power over their own choices and attitudes. We can only change ourselves, not others. It takes heroic courage not to help a loved one when helping might be enabling the loved one’s pattern of dysfunctional behavior. Moreover, it takes heroic courage to take charge of one’s own life by confronting the alcoholic about the dysfunctional pattern, setting boundaries with the alcoholic, or perhaps even terminating the relationship with the alcoholic.

In any difficult situation, there are always things one can change and options one can consider, although it may take great courage to try something that is completely different and outside one’s proverbial comfort zone. It requires a heroic consciousness to consider all the things that can be changed with the goal of doing what is best for all concerned. In Groundhog Day, Phil Connors could have stayed in bed in his hotel room for all eternity. But instead, he accepted his powerlessness over the time loop and became focused on changing the one thing he could change: himself.

The third and final component of the serenity prayer asks for “the wisdom to know the difference” between those things over which we are powerless and those things over which we do have power. This wisdom lies at the heart of heroic behavioral consciousness, healthy self-regulation, and sage empowerment. I call this the wisdom of tempered empowerment.

Pre-heroes cannot easily distinguish between what they can control and what they cannot, nor are they adept at anticipating the efficacy of their efforts to control others or their environment. As a result, pre-heroes can easily become meddling or enabling individuals who do more harm than good (Beggan, 2019). People with heroic consciousness possess the wisdom of tempered empowerment by recognizing the difference between situations that call for action and situations that call for inaction. The heroically conscious individual has the courage to do great things as well as the courage to avoid the kind of helping behavior that may be harmful, futile, counterproductive, or unnecessary.

–

This blog post is excerpted from:

Allison, S. T. (2019). Heroic consciousness. Heroism Science, 4, 1-43.

Like this:

Like Loading...

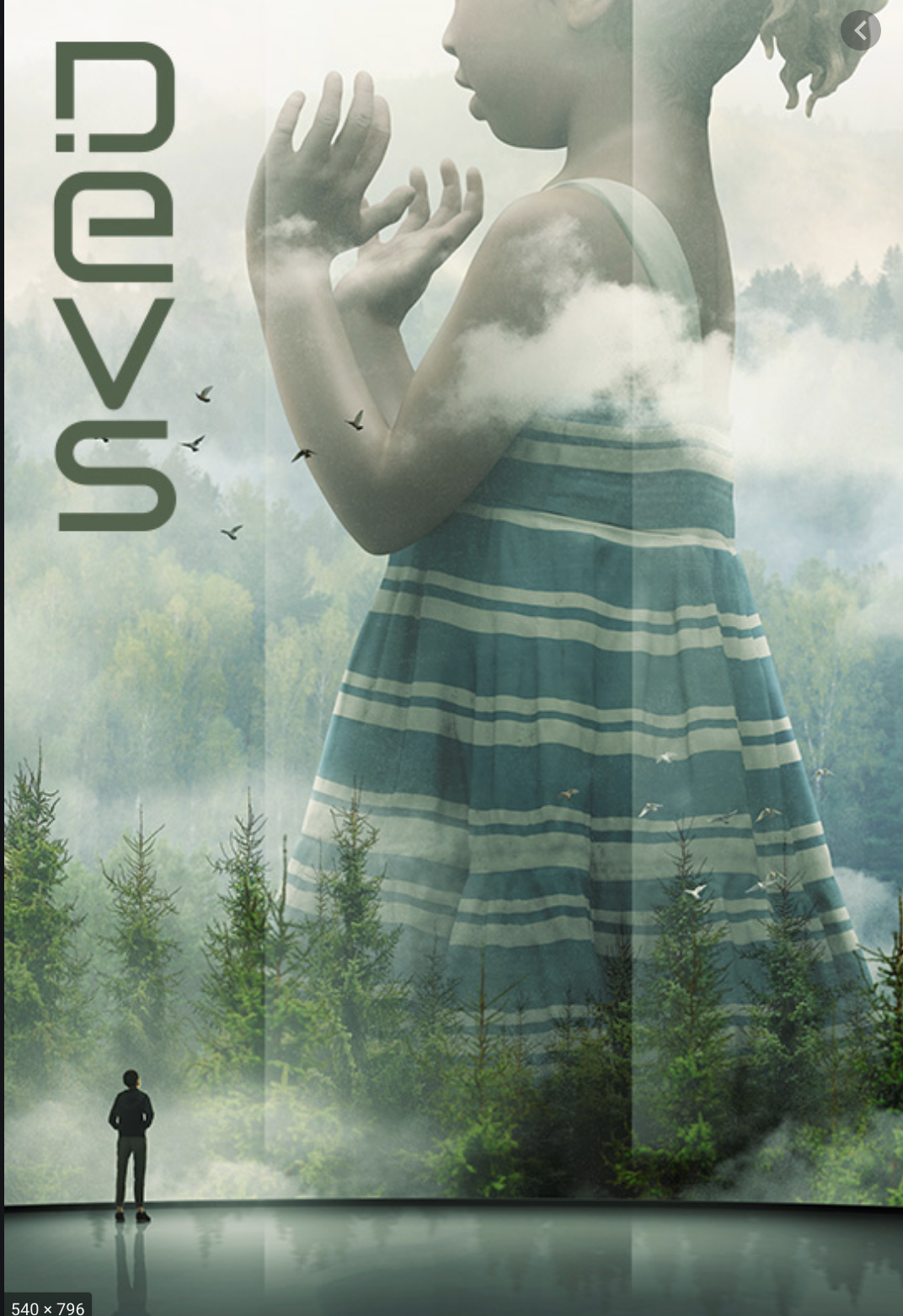

His girlfriend Lily has these same qualities and the two appear to have a close relationship. Amaya’s top secret Devs operation is shrouded in mystery. This element of mystery is a vastly underrated aspect of heroism and villainy. What role does mystery play? It inflames our heroic imagination. It especially ignites our imagination for the presence of potential evil.

His girlfriend Lily has these same qualities and the two appear to have a close relationship. Amaya’s top secret Devs operation is shrouded in mystery. This element of mystery is a vastly underrated aspect of heroism and villainy. What role does mystery play? It inflames our heroic imagination. It especially ignites our imagination for the presence of potential evil. actual portal into our true past and into what seems to be our exact future. I love how Devs invites us into the philosophical argument about free will versus determinism and gives us data supporting both positions. Mustn’t the true reconciliation of the free will vs. determinism duality reside in its nonduality? Lily’s final actions in the last episode demonstrate the fallibility of taking an all-or-nothing position on this issue.

actual portal into our true past and into what seems to be our exact future. I love how Devs invites us into the philosophical argument about free will versus determinism and gives us data supporting both positions. Mustn’t the true reconciliation of the free will vs. determinism duality reside in its nonduality? Lily’s final actions in the last episode demonstrate the fallibility of taking an all-or-nothing position on this issue.

By Scott T. Allison

By Scott T. Allison