“Death throws life out of balance, and it’s up to us, the living, to try to bring that balance back.” – Rick Hutchins

Recently, I’ve been mulling over the link between heroism and death. In 2014, several events in Richmond, the city I love and call home, had me reeling. Years have passed and my heart and my head have still not yet recovered.

On May 10, 2014, two of my colleagues at the University of Richmond died tragically in a hot air balloon accident. I knew one of the women, Ginny Doyle, the Associate Head Coach of the women’s basketball team. She is described by everyone who knew her as the shining light of the university. She was a stellar athlete and even better person.

The same praise is being heaped upon Natalie Lewis, who also perished. Natalie was a natural leader, a young woman with so much promise she was named Director of Basketball Operations in her early twenties. She exuded kindness and had a smile that lit up every room she entered. These two individuals are gone but not before leaving an indelible imprint on our small but loving campus community.

I think about Ginny and Natalie the same way I think about my sister Sheree, who succumbed to cancer only a few months earlier. In a flash, our short lives can be rendered shorter than we could ever imagine. We had best be mindful about how we use what precious time we have.

I wrote about my sister and called her, “the quiet hero.” The same can be said about  Ginny and Natalie. They quietly touched the lives of many people in ways that will have a ripple effect throughout eternity. Kindness begets kindness, I am sure of it.

Ginny and Natalie. They quietly touched the lives of many people in ways that will have a ripple effect throughout eternity. Kindness begets kindness, I am sure of it.

Death has a way of humbling all of us. Before they died, it’s quite possible that few would use the ‘hero’ label to describe Ginny, Natalie, or Sheree. Part of this may be due to death heightening our evaluations of those who pass. But I also believe that death amplifies our sensitivity and appreciation of the inherent goodness in people. Death directs our attention to what really matters in life – love.

In the end, our loving actions define us.

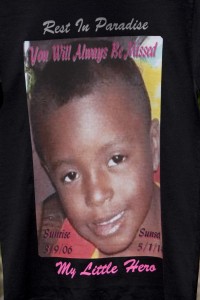

If love is paramount, then it is especially heart-gutting when someone dies while performing an act of love. This is precisely what happened here in Richmond in late April of 2014. Eight-year-old Marty Cobb was playing outside when he saw his older sister being attacked by a 16-year-old boy. Marty rushed to help her and died at the hands of the older boy while trying to protect her. Marty’s sister recovered from her injuries. But Marty is forever gone.

It is unthinkable for a precious young boy to die from any cause, but when the boy dies while saving his sister’s life, the pain is — to paraphrase Rudy Giuliani — more than any of us can bear. Marty didn’t just live a life of a hero, as did Ginny, Natalie, and Sheree. He died a hero. There is no nobler way to go.

Marty’s selfless act of ultimate sacrifice has only compounded the outpouring of grief, love, and heartache that Richmond’s  citizens are now feeling. Summing up Marty perfectly, a makeshift sign placed outside Marty’s home reads, “Pound for pound, year for year, few greater heroes if any.”

citizens are now feeling. Summing up Marty perfectly, a makeshift sign placed outside Marty’s home reads, “Pound for pound, year for year, few greater heroes if any.”

The multi-layered connection between death and heroism exists for a reason. We all are called to pause and reflect about the loving lives of those who have been suddenly wrenched from us. Their lives inspire us all because they call us all.

Three beloved Richmonders are no longer with us. Drawing attention to their immense love deepens our sadness but also instills a joyous recognition that their heroism, quiet and otherwise, is an extraordinary gift fated to reverberate throughout eternity.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –