If you had the choice of any super power, which would you choose?

This question is asked frequently at dinner parties, in coffee houses, on Internet community forums and on personality tests. It’s always interesting and revealing to hear how each person would take advantage of one chance to make an exception to the laws of reality, to find out which power they think is the greatest. But it’s usually answered as a lark, with whimsy — time travel to go back and invest in Microsoft or invisibility to hang out in the high school locker room — or with a darker undercurrent of wish fullfilment — super strength or mind control to take revenge on those who have done us wrong. Only a small number seem to respond thoughtfully on what power would bring the greatest good to the greatest number.

Only a small number seem to fantasize about being a hero.

Because that’s the problem with super powers. Power corrupts. And absolute power corrupts absolutely.

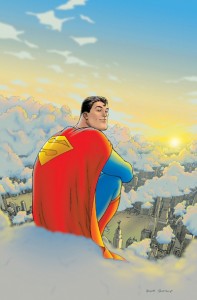

The original super-hero was Superman; he provided the template for all who were to follow and he was gifted with multiple powers. He was super strong, he could fly and see through walls, and move faster than the speed of sound.  He could melt lead just by looking at it and his very breath could surpass the strength of a hurricane. Bullets and lasers bounced harmlessly off his skin. He could pass through the heart of a star unharmed. If ever there was a man with absolute power, Superman was he.

He could melt lead just by looking at it and his very breath could surpass the strength of a hurricane. Bullets and lasers bounced harmlessly off his skin. He could pass through the heart of a star unharmed. If ever there was a man with absolute power, Superman was he.

But consider how this man lived. The most powerful man in the world worked as an anonymous reporter, disguised as a mild-mannered everyman, bullied by his boss and rebuffed by the women at the office. His downtime was spent in his Fortress of Solitude, in quiet contemplation among the souvenirs and mementos of his extraordinary life. He could have had any woman he wanted, by force or charisma; he could have had any riches that he desired; he could have ruled the world, for no one would have dared deny him anything. Instead, he used his power to protect the planet, to defend the defenseless and to help down cats who were stuck up in trees.

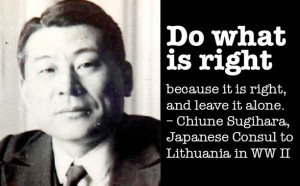

From the day we are born, we are told that power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely. But Superman, the iconic figure of our subconscious desire for greatness, puts the lie to that. He tells us that you can have all the power in the world and still live a life of humility and generosity. He shows us that the greatest power is incorruptibility.

None of us will ever leap a tall building in a single bound, change the course of a mighty river or bend steel in our bare hands. Seldom is any one person put in a position to save the world or to alter the destiny of Humanity. But we can always return that lost wallet with the contents intact, tell the truth when it matters, stand our ground when it’s easier to walk away or do unto others as we want them to do unto us.

Everyone has the potential to be a hero because everyone has the power to be incorruptible.

– – – – – – – – – – –

Rick Hutchins was born in Boston, MA, and has been an avid admirer of heroism since the groovy 60s. In his quest to live up to the heroic ideal of helping people, he has worked in the health care field for the past twenty-five years, in various capacities. He is also the author of Large In Time, a collection of poetry, The RH Factor, a collection of short stories, and is the creator of Trunkards. Links to galleries of his art, photography and animation can be found on http://www.RJDiogenes.com.

This is Hutchins’ fourth guest blog post here. His first two, on astronaut and scientist Mae Jemison and the Fantastic Four’s Reed Richards, can be found in our book Heroic Leadership.