By Scott T. Allison and George R. Goethals

By Scott T. Allison and George R. Goethals

In Part 1 of this series, we introduced the concept of the Heroic Leadership Dynamic, which we define as a system of psychological forces that can explain how humans are drawn to hero stories, how they benefit from these stories, and how the stories help people become heroes themselves.

We suspect that early humans first told hero stories at the end of the day, in the darkness, huddled around fires. These narratives supplied meaning, hope, and a welcome escape from the miseries of life. The earliest known hero tales, such as Gilgamesh, Etana, Odysseus, and Hesiod, taught important values, offered role models, provided inspiration, and healed psychic wounds.

We propose that people benefit from hero stories in at least two essential ways. These stories serve epistemic and energizing functions. The epistemic function refers to the wisdom that hero stories impart to us. The energizing function refers to the ways that hero stories heal us, inspire us, and promote personal growth. Let’s look at these two functions in greater detail.

THE EPISTEMIC OR WISDOM FUNCTION

Theologian Richard Rohr argues that hero stories encourage people to think transrationally about ideas that seem to defy rational analysis. The word transrational means going beyond or surpassing human reason.  Hero stories reveal truths and life patterns that our limited minds have trouble understanding using our best logic or rational thought. Transrational phenomena that commonly appear in hero stories include suffering, sacrifice, meaning, love, paradox, mystery, God, and eternity. These phenomena beg to be understood but cannot be fully known using conventional human reason.

Hero stories reveal truths and life patterns that our limited minds have trouble understanding using our best logic or rational thought. Transrational phenomena that commonly appear in hero stories include suffering, sacrifice, meaning, love, paradox, mystery, God, and eternity. These phenomena beg to be understood but cannot be fully known using conventional human reason.

Hero stories unlock the secrets of the transrational.

How do hero tales help us think transrationally? We believe that there at least three ways: Hero stories (a) reveal deep truths, (b) illuminate paradox, (c) develop emotional intelligence. Let’s examine each of these:

A. Hero Stories Reveal Deep Truths. According to Joseph Campbell, hero stories reveal life’s deepest psychological truths. They do this by sending us into deep time, meaning that they enjoy a timelessness that connects us with the past, the present, and the future. Richard Rohr notes that deep time is evident when stories contain phrases such as, “Once upon a time”, “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away”, and “they lived happily ever after.” By grounding people in deep time, hero stories reinforce ageless truths about human existence.

Hero stories also reveal deep roles in our human social fabric. Norwegian psychologist Paul Moxnes believes that the deepest roles are archetypal family roles such as mother, child, maiden, and wise old man. Family role archetypes abound in classic hero tales and myths, where there are an abundance of kings and queens, parents, stepparents, princesses, children, and stepchildren. Interestingly, Moxnes’ research shows that even if hero stories do not explicitly feature these deep role characters, we will project these roles onto the characters. His conclusion is that the family unit is an ancient device for understanding our social world.

B. Hero Stories Illuminate Paradox. Hero stories shed light on meaningful life paradoxes. As author G. K. Chesterton once observed, paradox is truth standing on her head to attract attention. Most people have trouble  unpacking the value of paradoxes unless the contradictions contained within them are illustrated inside a good story. It turns out that hero stories are saturated with paradoxical truths, such as those mentioned by Joseph Campbell in the quote that began Part 1 of this series. Let’s look at each of them:

unpacking the value of paradoxes unless the contradictions contained within them are illustrated inside a good story. It turns out that hero stories are saturated with paradoxical truths, such as those mentioned by Joseph Campbell in the quote that began Part 1 of this series. Let’s look at each of them:

* Where we had thought to find an abomination, we shall find a god. Carl Jung is famous for saying, “what you resist persists.” Every human being encounters difficult people and challenging issues in life. Hero stories teach us that avoiding these people and issues is not the answer. Once we confront our dragons, they can become the seeds of our redemption.

* Where we had thought to slay another, we shall slay ourselves. What Campbell means here is that when heroes face their greatest fears, they are entering the dragon’s lair. And when heroes slay the dragon, they are slaying their false selves or former selves, thereby allowing their true heroic selves to emerge.

* Where we had thought to travel outward, we shall come to the center of our own existence. In the opening act of every hero story, the hero leaves her safe, familiar world and enters a dangerous, unfamiliar world. Going on a pilgrimage of some type is a necessary component of the hero journey. Hero stories teach us that we have to leave home in order to find ourselves.

* Where we had thought to be alone, we shall be with all the world. The hero’s journey is far from over once the dragon has been slain. Campbell observes that the now-transformed hero in myth and legend will now return to his original familiar world and transform it in significant ways. The hero, once alone on his journey, becomes united and in communion with the world.

transform it in significant ways. The hero, once alone on his journey, becomes united and in communion with the world.

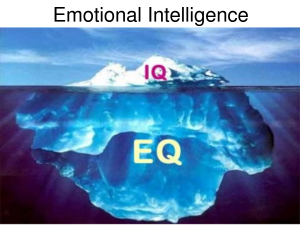

C. Hero Stories Develop Emotional Intelligence. Psychologist Bruno Bettelheim believed that children’s fairy tales were useful in helping people, especially children, understand emotional experience. With their many dark, foreboding symbols and themes, such as witches, abandonment, neglect, abuse, and death, these heroic fairy tales allow people to experience and resolve their fears.

Bettelheim believed that even the darkest of fairy tales, such as those by the Brothers Grimm, add clarity to confusing emotions. The hero of the story emerges as a role model by demonstrating how one’s fears can be overcome. The darkness of fairy tales allows children to face their anxieties and grow emotionally, thus better preparing them for the challenges of adulthood.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – –

This series is based on a chapter in our book, Conceptions of Leadership, published by Palgrave Macmillan. The citation for this chapter:

Allison, S. T., & Goethals, G. R. (2014). “Now he belongs to the ages”: The heroic leadership dynamic and deep narratives of greatness. In Goethals, G. R., et al. (Eds.), Conceptions of leadership: Enduring ideas and emerging insights. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1057/9781137472038.0011

I’m a little uncomfortable with the concept of transrationality. The idea of “going beyond or surpassing human reason” has a couple of negative implications. One is that reason has limits, and the other is that positive values are irrational; both are bad arguments to make. I think what is happening here, rather, is an example of a human being using all the tools available in the service of reason– in other words, both intellect and imagination. What is human life, after all, but the synergy of the arts and sciences? Thought complementing knowledge, perspective complementing observation, and so on. The idea in some schools of thought that rationalism is somehow lacking in humanity is somewhat self-defeating.

Thanks for your comment, RJ. Personally, I have no problem accepting my limited ability to understand, through reason, the meaning behind suffering, eternity, love, paradox, and other transrational phenomena. Storytelling brings those concepts to life and allows us to hold their inherent contradictions in a creative tension that is both useful and energizing.

It may amount only to semantics, but I feel it’s an important distinction, given the ongoing problems the world has with anti-intellectualism.

I hope we’re not taking an anti-intellectual stance here. Transrationalism (to me) implies that there are just some things that are best understood within a narrative structure. In your original comment, RJ, you use the term ‘irrational’, which we never use. Transrationality is perhaps a higher form (or a deeper form) of rationality.

Hi Scott, i am your twitter friend and I believe with people benefit from hero stories in at least two essential ways. Thank for the complete detail

Kia ora & Bula or Greetings Scott,

Like your twitter friend #newhotelus, i too, am friends with you on twitter.

This is an interesting piece. I quite enjoy reading the details & expressions used such as; “deep time”, ” deep role” etc. It opens up a new dimension. Makes me yearn to reconnect with that aspect again on a personal level.

I also enjoyed your use of Chesterton’s thoughts on the topic of ‘Paradox’. The quote you used read; “Paradox is truth standing on her head to attract attention..”, (Chesterton). We often wonder through life’s journey missing this point.

Thanks for a riveting article.

Have an awesome Christmas & New Year2016.