A great deal has been written and spoken about the 35th President of the United States, John F. Kennedy, who was assassinated over 50 years ago in November of 1963. While nobody who was sentient at the time is likely to misremember Kennedy’s assassination – or the funeral that followed it, or the killing of his assassin on national television – recollections of Kennedy’s presidency are not so pure. Human memory is imperfect in many ways. At best, it is selective. Much worse, memory is prey to numerous biases, errors and distortions.

In Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, Mark Antony said at Caesar’s funeral, “The evil that men do lives after them; the good is oft interred with their bones.” One wonders whether the opposite is true in Kennedy’s case. People are generally aware of both good and bad aspects of the Kennedy years, but memory of the good seems to win out. On the positive side are his charismatic persona, inspirational rhetoric and ambitious agendas. The negatives include philandering, passivity on some crucial issues and deception about his health. All of these and numerous other aspects of his administration are debated endlessly.

But there is one aspect of JFK’s presidency that has received too little attention. Kennedy felt that the Limited Test Ban Treaty with the Soviet Union, signed in August and ratified in September of 1963 outlawing nuclear tests in the atmosphere, was one of the most far-reaching accomplishments of his administration.  In a commencement address at American University in June of that summer, sometimes called the “Strategy of Peace” speech, Kennedy outlined the possibility of a completely new relationship with Russians, moving beyond the Cold War and its tensions and standoffs.

In a commencement address at American University in June of that summer, sometimes called the “Strategy of Peace” speech, Kennedy outlined the possibility of a completely new relationship with Russians, moving beyond the Cold War and its tensions and standoffs.

That speech and the test ban treaty were part of his evolving reexamination of super power relations. As a result, the word “détente” entered the American political vocabulary during the last weeks of the Kennedy administration, although it did not become widely used until the Nixon and Ford eras in the 1970s. Kennedy’s initiatives suggested what was possible for other willing presidents to achieve by way of reducing tensions with our Communist adversaries.

Kennedy had seen war himself and had seen men under his command die. He also had seen the United States and the Soviet Union come far too close to nuclear annihilation. He wanted very much to find ways to move beyond the Cold War and nuclear confrontation. His hard-line National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy once quipped to an aide that there were only two pacifists in the White House, “You and Kennedy.”

But Kennedy was no pacifist. He would have fully endorsed the Ronald Reagan/George H. W. Bush mantra that “peace through strength works.” But he was committed to building what would later be called a “new world order.” In his last months he consulted with Russian diplomats about joint ventures in space. He also came to believe that further American involvement in Viet Nam would never sustain the South Vietnamese regime. He announced the redeployment of 1,000 military advisers from that country.

Although the question is one of those persistent unknowns, it seems most probable that the full-scale American war in Viet Nam would  not have happened in a second Kennedy term. More generally, it seems safe to imagine that the world would have been very different had Kennedy not been assassinated. His intelligence and what psychologists call “openness,” that is, curiosity and broad interest in ideas and feelings, enabled him to grow and become ever more realistically flexible. These are personal qualities that almost always serve leaders well.

not have happened in a second Kennedy term. More generally, it seems safe to imagine that the world would have been very different had Kennedy not been assassinated. His intelligence and what psychologists call “openness,” that is, curiosity and broad interest in ideas and feelings, enabled him to grow and become ever more realistically flexible. These are personal qualities that almost always serve leaders well.

In the decade after Kennedy’s assassination, some held that within a generation JFK largely would be forgotten, remembered, if at all, as a young and promising president who served for a short time with mixed results. It was foreseen by few then that he would capture the country’s attention with unprecedented focus in the year 2013. But memory, both individual and collective, works in unpredictable ways.

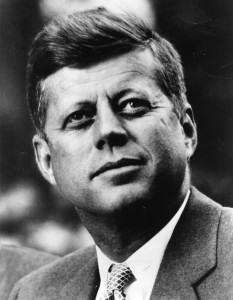

Images of Kennedy are pervasive and forever forged in our memories. We hear his voice, see him smile, listen to his banter with reporters and his speeches and comments on matters both large and small. After five decades, it may be time to organize our own recollections and what we have learned as we grasp an unforgettable American original.

We might start with remembering what he said at American University: “For in the final analysis, our most basic common link is that we all inhabit this small planet. We all breathe the same air. We all cherish our children’s future.”

– – – – – – – – – – – –

Dr. George R. Goethals holds the Robins Professorship in Leadership Studies at the University of Richmond’s Jepson School of Leadership Studies

I have no direct personal memory of Kennedy– I was 2 1/2 years old when he was killed. But his image, his personality, his ideals, and his presence permeated the world that I grew up in. He was the embodiment of the 60s. Youthful, energetic, idealistic. Ready, willing, and able to break with the past and summon the future, to abandon mistakes and find new solutions. To bring America closer to becoming itself.

It’s ironic that the 60s, this era of great change, was dominated by presidents Johnson and Nixon, who represented the failures of the past. Much of what was accomplished then was in response to their policies, their culture, and their war. If Kennedy had lived, would American culture had evolved more smoothly, less violently, perhaps progressed further without triggering the conservative backlash of the Reagan years? Or would the message have been diluted by disillusion and politics without a shock to the system to provide inspiration? One would like to think that the world can be improved without the martyrdom of good people.

Excellent piece. One also has to wonder how Kennedy would have fared in our era of scandal and sensationalism. In the 60s people seemed to care less about the personal foibles of their politicians and celebrities. Would Kennedy’s personal failings have derailed his political accomplishments in today’s world?

I was a high school sophomore when the unthinkable happened. I remember where I was, who I was with, how we didn’t believe, how we discovered that, as unbelievable it was, it had really happened. Until I read and reread the above, it has never occurred to me to wonder how my life might have been different if JFK had lived to serve two terms. In a peacetime armed forces, would having cousins in Jugoslavia have kept me from the clearance I needed to be a military linguist? Would that job have been to help create understanding among former adversaries for a lasting peace? Would gender have been more or less of an issue in my life? Much to think about….