By Sunny Lim

Maria G., who asks for her last name to be omitted, strolls inside an empty meeting room at the Sacred Heart Center and sits with her seven-year-old son, Francisco, a small, brown-haired boy with a penchant for running around.

Her stern face mirrors her son’s pout.

Maria starts speaking rapidly in Spanish to Father Jack, updating him on her activism and the causes that move her, from making Richmond a sanctuary city to creating better lives for immigrants living in Jeff Davis.

Then she shifts to talking about Francisco and the issue that concerns her.

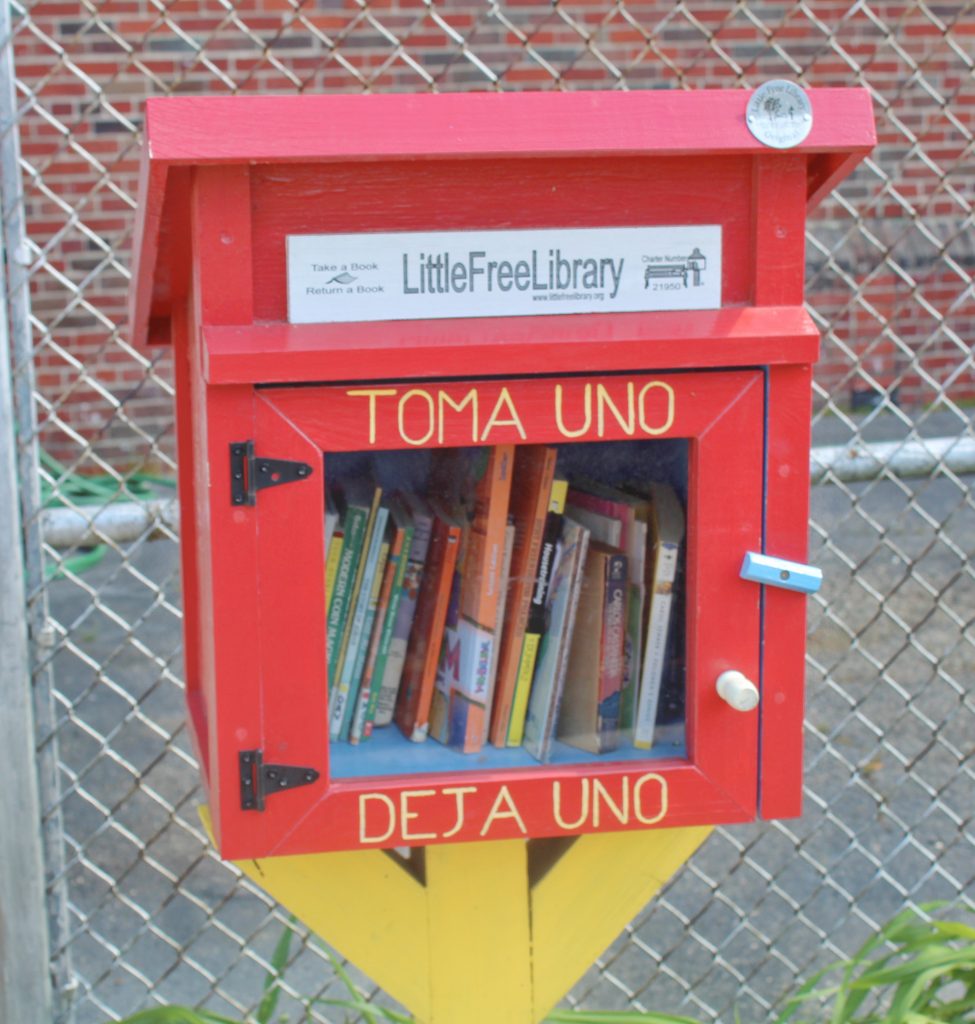

“His teacher scolded him and said that he shouldn’t speak Spanish,” Maria said. “He was so upset that he stopped speaking Spanish for a little bit, but I told him that being bilingual is good. Knowing more languages gives you more opportunities later in life.”

Father Jack reassures her, and she smiles, describing how Francisco translated English books into Spanish for his friends and classmates. Listening, Francisco smiles and tucks his face into his arm as his ears turn red as the file cabinets in the room.

For the Latino community and all immigrants, language is a claim to their identity. They use their native language to share experiences, emotions, and information. But in most of these families, children are the ones who learn English first and assume care-taking roles as they translate tax documents, school forms, and bills for their parents. Although they’re proud of their bilingualism, they sometimes lash out at their parents because they resent the responsibility thrust upon them.

Losing one’s native language is akin to losing a sliver of your heart. When we learn a second language, parts of our first begin to fade away. This started to happen to me, growing up in California as the daughter of South Korean immigrants. It begins when you forget how to say a noun like “stairs” or other basic vocabulary in your native language. Later you misplace sentence structures and basic grammar. One day you’re unable to read a sign in your native language without reaching for a dictionary. And as the language drifts away, it hurts to wrack your mind, and your soul, in search of the definition.

Maria’s son, however, hasn’t lost his Spanish. He has mastered English, and his Spanish, spoken at home and on the playground, remains with him. I will always remember the pride in Maria’s voice, speaking Spanish, and Francisco’s sly bilingual smile, hidden in his sleeve.

Father Jack Podsiadlo emphasizing the importance of bilingualism and education with one of his favorite books, Tattoos on the Heart: The Power of Boundless Compassion. (Photo by Sunny Lim)