by Joshua Kim

June 5, 2017. Today, I voted on a poll hosted by the Richmond Times-Dispatch in regards to whether or not the monuments on Monument Avenue — that honor several key Confederate figures — should be taken down.

This debate has fired up again, recently, after the removal of similar Confederate statues in New Orleans, the question being: Does dismantling these statues erase parts of our history?

Heritage not hate.

The phrase above is popular phrase used to defend the Confederate flag. With it, supporters make the claim that to wave the Confederate flag is to celebrate their forefathers and mothers, their ancestors who lost their lives fighting for their beliefs and pride. This depicts the South in a glorious fashion; as a center of sweet tea and honeysuckles, butter biscuits and warm sunbathes on big green lawns.

What this imagery lacks; however, is the stark reality that the South, specifically, Richmond, Virginia, was one of the leading slave markets of its time.

More so, what this depiction fails to tell us is the active offensive maneuvers Virginia politicians, businessmen, and everyday citizens made in order to create a racial hierarchy that continues to disenfranchise black people today.

“Before the rubble had been cleared from the devastated business district of the capital city, Richmond’s press began to campaign against voting rights for its freed black citizens” (Campbell, Richmond’s Unhealed History, 131).

A key figure in this campaign was Edward A. Pollard, wartime editor of the Richmond Examiner. Pollard is most famous for his book, The Lost Cause (1866), which created a narrative of the South that focused on its intellectual superiority and cultural influence and encouraged the South to retain its pride:

“(The South’s) well-known superiourity in civilization…has been recognized…by the intelligent everywhere; for it is the South that in the past produced four-fifths of the political literature of America, and presented in its public men that list of American names best known in the Christian world. That superiourity the war has not conquered or lowered; and the South will do right to claim and cherish it” (Campbell, quoting Pollard, 131-132).

This ideology resurged during the 1890s.

According to Campbell, “Monuments in Richmond show the power of Confederate themes in that time. The first…the Lee Monument, was unveiled on May 29, 1890. The ceremony began with a procession of 15,000 Confederate veterans leading a crowd which eventually totaled more than 100,000…” (Campbell, 136).

Immediately following the war, Richmond made it a political priority to reinstate dominance over its black population, and part of that process was the creation of these statues celebrating and commemorating Confederate war-time heroes.

But this is not just about statues, but actual laws that were put in place to limit black citizens from moving up the social ladder.

For example, on January 15, 1866, an extreme vagrancy law was passed which made unemployment illegal.

This was later prohibited nine days later by General Alfred Terry; however, its effects were still in place. Campbell notes that during this time “…white employers had already made agreements not to hire freedmen at normal wages, thus forcing wages to be depressed and providing an opportunity for the enforcement of the vagrancy statute” (Campbell, 132).

By denying black workers living wages, white employers were able to maintain economic dominance and establish a pseudo-slavery:

“The ultimate effect of the statue will be to reduce the freedmen to a condition of servitude worse than that from which they have been emancipated a condition which will be slavery in all but its name” (Campbell, 132).

In addition to economic oppression, white people also made it extremely difficult for black citizens to vote/gain power in office. They did this through poll taxes, literacy tests, intimidation, etc. Yet, despite these tactics, from 1867-1868, black people made up the majority of Richmond’s registered voters (Campbell, 134).

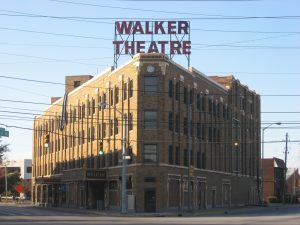

To combat this, the city government began to create segregated neighborhoods through “urban renewal:”

“From the very beginning, urban renewal focused on ‘blighted Negro housing.’ By this was meant the black neighborhoods of town. …Beginning with the establishment of the housing authority, white Richmond tore down Jackson Ward block by block… Over the next thirty-five years, in the name of urban renewal, the city council pursued a plan that destroyed or invaded every major black neighborhood in the city.” (Campbell, 152-153).

These residents were often relocated to projects, or they were forced into white neighborhoods. Then, the whites that had been “displaced” were sold housing in new suburbs in other counties, thus, effectively segregating white and black citizens.

White Richmond created a system in which black citizens suffered economic, social, and geographic oppression for the last century. We see the effects of it today when we look at how our community is still segregated by race, how black people are disproportionately in poverty compared to whites, and how we still have statues of Confederate leaders in our city.

When we discuss these monuments and the sentiments placed on them, let us not forget those who were most deeply affected by these men — black people.

Everyday those statues stand as a reminder of the deep rooted hatred and oppression white Richmond citizens have against our black population. They are reminders that, although at face value our city has grown, deep down, we are still the capital of the Confederate south.

Heritage is hate.

Joshua Hasulchan Kim is from Colonial Heights, Virginia. He is a sophomore at the University of Richmond who is double majoring in Journalism and French. Joshua is involved in various clubs on campus: He is the co-president of Block Crew dance crew, the opinions editor for the Collegian newspaper, and is the Co-Director of Operations for the Multicultural Lounge Building Committee. Joshua joined the project as part of the Spring 2017 independent study (RHCS 387) and is currently expanding this research with the support of an A&S Summer Research Fellowship.