By Hunter Moyler

Notwithstanding my fifth-grade teacher’s contention that the Confederate battle flag was something “we” used during the war and a banner all southerners, particularly Virginians, could flaunt proudly, I have always read it as something bad. A symbol worthy of loathing, and, at times, fear.

My earliest recollection of the flag comes from when I was a chubby-cheeked Cub Scout. The Pack attended a small reenactment of a Civil War battle. (The battle didn’t take place in our town, but since it is Virginia, you’d best believe it was probably one or two miles over the hill.) When I saw the Johnny Wannabe Rebs step out with St. Andrew’s Cross, I promptly stood up and shouted, “Boo! The South! You guys stink!” causing everyone’s heads to swivel toward me like southern cannons rearing to fire. And I was the Yankee.

Dad and I went home a little early that day.

Anyway, the point is that my mind has admittedly never left much room for the reinterpretation of the Confederate flag. Besides being flown by men willing to die for the idea that people like me could be counted as property, its popularity among white supremacist groups and use by southern states as a middle finger thrust at a federal government pushing for racial integration haven’t done much to ameliorate its status in my eyes. Nor has the fact that the man who murdered nine black churchgoers in 2015 to incite a “race war” took photos posing with it and posted them to the internet.

Recently, I saw a collection of rebel flags in precisely the type of place I think most of them ought to be: The Museum of the Confederacy in Richmond.

The flag exhibit, “Colors of the Gray: Consecration and Controversy,” is on the museum’s top floor. It displays an impressive collection of national and regimental Confederate flags that’ve been donated to the museum. Even as someone with an appreciation of Civil War history, I was struck by the sheer diversity of the old flags. They constitute quite the spectacle, if anything.

Displaying artifacts of the bygone nation is, of course, one of the chief aims of the museum, and in this regard the museum has done a splendid job. However, I must confess that I don’t think it devotes enough space to the controversy of its flag as much as it does its consecration.

For all the banners it displays, the exhibit has scant information about the modern use of the flag — which, unfortunately for proponents of the “heritage” mode of looking at it, has undisputedly been dominated by… well, no need to list them more than once. A museum placard made one reference to this, I think, but didn’t go into depth.

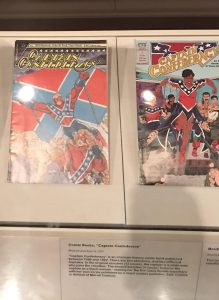

Most of the information about the flag’s modern use was found in a much smaller exhibit within the exhibit called “Confederate Flags in the 20th Century.” Under a display case, there was one pop culture item that caught my eye and made me ponder the flag’s stature post-Civil Rights Movement.

There were two Captain Confederacy comic series, both created by Will Shetterly and published in 1986 and 1991, respectively. The first Captain Confederacy was a White man, but his successor was a Black woman — making the second Captain Confederacy the first Black woman character to have her own series in which she was the title character, as the museum takes care to point out.

It’s not easy to discern from the covers, but the Captain Confederacy comics were, in fact, a clever alternate history tale that comments on American politics and race relations as opposed to neo-Confederate wish-fulfillment. Shetterly said in a 2006 interview that the comics were especially relevant in the post-9/11 nation, on account of the “neoconservative jingoism of the Bush supporters.” Not exactly something you’d anticipate hearing from the writer of a book emblazoned with the Southern cross, no?

The story is set in an alternate timeline, about a century after the Confederacy bested the Union on the battlefield. This led not only to an independent Dixie, but also the utter sundering of what was once the United States. Aside from the USA and CSA, there’s also the People’s State of California, the Free State of Louisiana, Deseret, and (of course) a free Texas.

Slavery itself plays a surprisingly minimal role in the comic’s plot, although the cult of white supremacy that sprang from it performs center stage. In this fictionalized history, the South abolished the “peculiar institution” not long after its victory. Dixie is light years away from an equitable utopia, however. Blacks and other people of color are lawfully mandated to live as second-class citizens nationwide in a system perhaps most analogous to South African apartheid.

Naturally, this strains the country’s relations with the other North American nations. And, as is often the case with terrible places to live with terrible civic policies, there’s considerable civil unrest in the Confederacy. This is the reason President Lee’s government created the eponymous hero.

Captain Confederacy, as it turns out, is actually a mere celebrity, a propaganda puppet meant to inspire the population to remain deferential to the government. He’s an actor, hired by the government to battle “supervillains” (also actors) on live TV. The fights are totally staged, but the public is none the wiser. The shows are intended to turn the tide of public opinion against those whom the government deem contemptible: insolent Blacks and whoever else threatens the social order. The twist? The actors were given real superpowers – thanks to a super soldier serum.

It all changes when the Captain, fed up with his corrupt government, decides to defect to the Union. As he and his allies are pursued by Confederate authorities, he must decide whether to return to playing a fake hero or becoming a real one. The comics themselves can be found in their entirety on the writer’s blog.

The flag’s use here is interesting. It is, ostensibly, showing off the flag as a symbol of power and pride, but the pages reveal it to be the symbol of prejudice that many hold it to be. I think it’s educational in that regard. I have no doubt that I’m not the only one who doesn’t hold the flag in high esteem, and the author does a good job of using that to make a point. I think the Museum of the Confederacy would’ve done well to include that point and explain more context about the comic and the flag’s role in it.

The image of a Black woman as Captain Confederacy is too fascinating not to spark an interest. In-universe, she is Kate Williams, the original captain’s lover and formerly one of the “villains” his persona would regularly combat. And, thankfully, she is no more a regressive character than was her predecessor but rather a fully-developed one in a well-crafted narrative. Do I take issue with the image of a Black woman wearing the Confederate flag? Honestly, not really. My dislike of the flag is not so profound that I cannot bear to see it, and I was in a Confederate museum with walls practically plastered floor to ceiling with different rebel flags. Without context, I did assume that it was a piece of neo-Confederate propaganda that probably painted a rosy portrait of a victorious, post-bellum Confederacy, distastefully using a Black woman as a prop to obscure its racist content. But I was mistaken.

Everything considered, I think the exhibit is fine but could do with a bit more context about the modern use of the flag, not only in the case of Captain Confederacy but with, well, everything. While I’m aware that the role of a museum is to present information, not push a certain interpretation of the artifacts it houses, let us not forget that not a single exhibit has ever been curated with absolutely no agenda in mind. And if the exhibit’s agenda is to teach about the consecration and controversy of the flag, I hold that more emphasis on the latter is crucial.

Hunter Moyler was raised in Chesapeake, Virginia. He is a rising junior at the University of Richmond, double-majoring in English and Journalism with a minor in Spanish. He is vice president of the College Democrats at the University of Richmond and co-editor of the Opinions section in The Collegian. This summer, he’s elated to have the opportunity to delve into the history of race relations in his state thanks to an A&S Summer Research Fellowship.

Very well written and a good read Hunter. I am proud of the man you are developing into.