by Cory Schutter

We’re halfway through the summer and I’m proud to say that I’m mastering the lost art of finding books in the library basement. Surrounded by the smell of forgotten books, I’ve learned that there’s something sacred about moving bookshelves, running my finger along book spines, and finding the right call number.

Black Thunder. PS 3503 .0474 B5x 1968.

I’ve found Arna Bontemps’ fictionalized 1936 account of Gabriel’s Revolt, and I start thumbing through the pages. I have to pause at the first words: “Time is not a river. Time is a pendulum.”

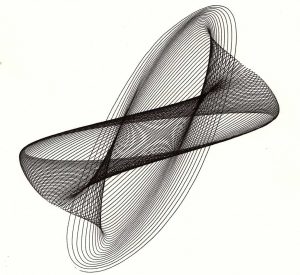

I imagine the way these swaying narratives sketch a harmonograph of stories with geometric relationships to us and each other. As students learning the work of activist archivists, we have a burden to bring the immaterial world into the physical one. This work triangulates forgotten stories, spreadsheets of metadata, and the creation of new spaces of memorialization. The pendulum is always swaying between the past and the present – stories meeting spaces.

The work of Untold RVA is to birth these spaces of meaning, to give life to stories from silent pages. Untold RVA seeks to celebrate the names that we’ve forgotten or ignored through the creation of physical spaces of veneration, taking shape in a mural or shrine. Our work engages the pendulum of time, recovering forgotten stories, pivoting the weight back to a place of honesty.

Arna Bontemps describes his journey to authoring a self-emancipation narrative through a series of choices and questions. He was tasked with the choice of selecting which story he should tell and compelled to share that narrative publicly. He was forced to question his role as a storyteller.

In Black Thunder, I’ve learned to tease out truth from a work of fiction. Bontemps memorializes Gabriel’s revolt through colorful personification, crisp leaves, dark nights, whispered conspiracies, and the slow drip of a courtroom battle. I’ve struggled to reconcile artistry with accuracy, to find evidence that backs up the narrative. How can I represent this curated body of evidence as vividly as Bontemps?

As a researcher for our community-based project, I’ve come to identify with this complicated task of questioning my role as a storyteller. The process of discovery is a personal one, and this work has lead me down into the lower basements of public memory. As a reader engaging a pendulum, what does it look like for me to read the past with the present in mind? When we are confronted the absence of representation in memorialization, how can we create truthful images of the past?

The narratives that I have encountered present me with problems. What stories should be told, and how can I share them? How can we share invisible stories, and what part do I play in this? In questioning my role as a storyteller, I’ve begun to wonder how I can marry authenticity with accuracy in order to best serve a community.

This makes me go back to the image of a harmonograph. Time is a strange and beautiful conjunction of lines, perhaps without a clear beginning or end. But the space is filled with connections and intersections, stories of movement and change. It’s exciting to play a part in interpreting these images and breathing new life into the stories we encounter.

In a 2016 production from NPR, Untold RVA’s Free Egunfemi talks about the hidden presence of human trafficking markets in pre-Civil War Richmond. As she walks through modern Richmond, she describes the auction blocks that used to populate street corners. “They’re not marked. There’s no memorials. There’s no signage. There’s no remnants. There’s no evidence. All of this stuff has been erased to time.” These street corners are silent.

Then there’s Libby Prison, which I first encountered in Julia Pollard’s book, Richmond’s Story. This Confederate prison was the site of brutal war crimes, and 50,000 prisoners passed through its doors. When Abraham Lincoln saw the prison after the surrender of Richmond, he envisioned the former prison to remain standing as a monument (288-299). Today, Libby Prison is a parking lot.

Just across the street from this parking lot, the Confederate States Army drilled enslaved black troops, often sent to Richmond as recruits by their human captors. Nelson Lankford shares this anecdote in Richmond Burning, and describes how sometimes enslaved persons would be assigned military service in lieu of the death sentence. These training grounds are beneath the Virginia Holocaust Museum.

These invisible stories encourage me to keep reading against the grain, collecting information, and curating a narrative for Richmond. This is just the beginning of our project to expose the past and create a resource for future activism.

As I reflect on our work, I go back to Arna Bontemps’ words: “I am, however, convinced that time is not a river.” When he wrote Black Thunder, he was met not with critical acclaim but an overwhelming sense of silence. He writes, “the theme of self-assertion by black men whose endurance was strained to the breaking point was not one that readers of fiction were prepared to contemplate.”

I hope that in our time and in our place, these themes of self-emancipation can be told. In the words of Free Egunfemi, “May it be so.”

Cory Schutter is a rising junior at University of Richmond, a double major in Rhetoric and Communication Studies and Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies. He is a Bonner Scholar, a Center for Civic Engagement Ambassador, and a Student Coordinator at UR Downtown.