by Johnnette Johnson

Johnnette Johnson is a rising senior from Marksville, Louisiana majoring in American Studies and French. Though her journey with the Race & Racism Project only began this summer, she has been involved in racial justice and community work since her matriculation at UR. A peer mentor and UR Downtown ambassador, when she’s not on campus or with family she’s out enjoying nature. She hopes to continue doing the work of commemorative justice and collective healing.

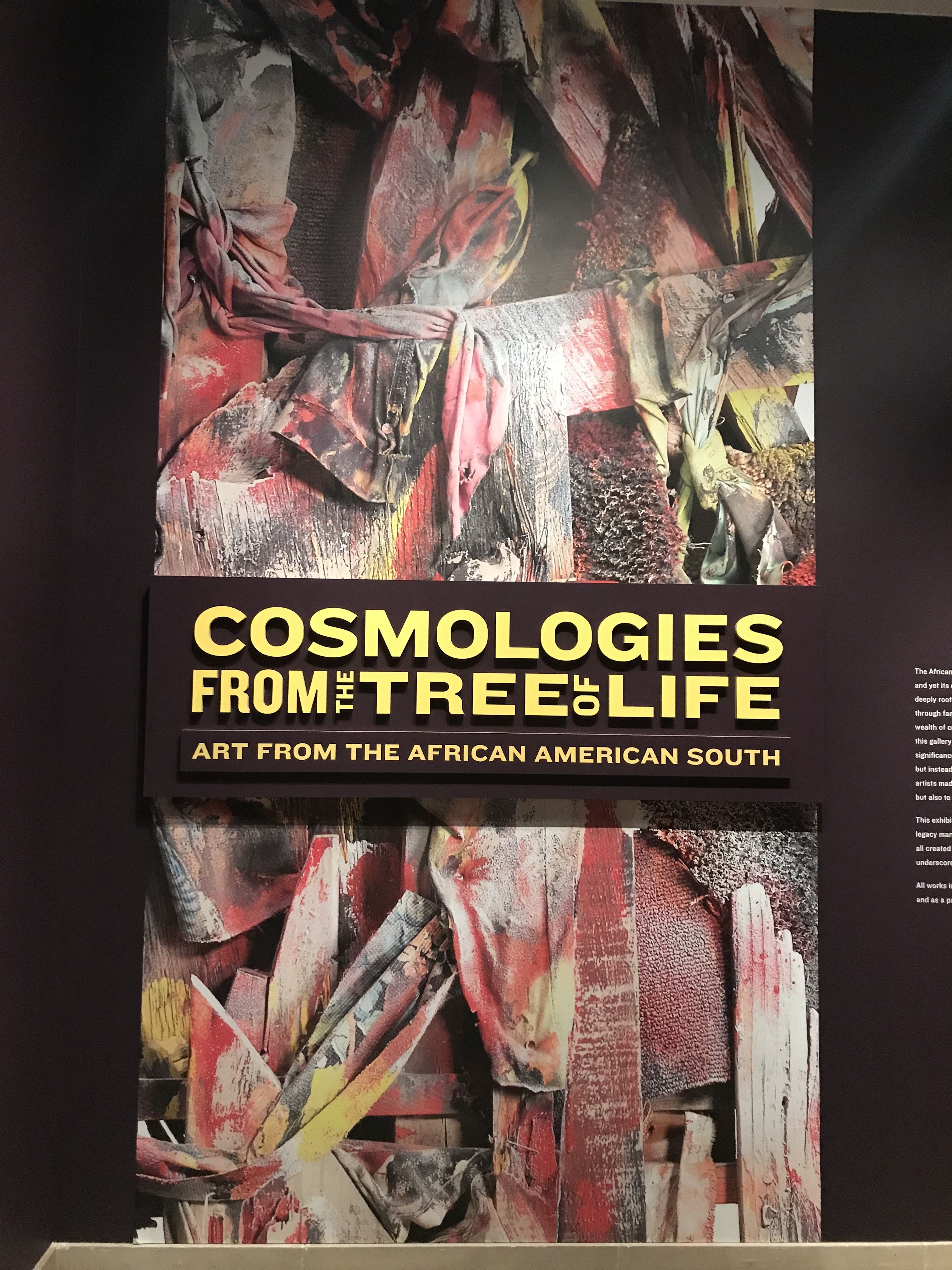

Cosmologies from the Tree of Life: Art from the African American South is the exhibit that caught my eye while on the search for my in-Richmond site visit.

Cosmologies from the Tree of Life: Art from the African American South is the exhibit that caught my eye while on the search for my in-Richmond site visit.

“Rooted in African aesthetic legacies, familial tradition, and communal ethos,” the exhibit set out to center artists who were often marginalized as uneducated or self-taught. After reading about the site, I was excited to see what it was about and I was curious to know how the artworks would draw a connection between “cosmologies,” “tree of life,” and “African American South.”

I walked through the European half of the floor to what seemed to be the museum’s ethnic corner to find Cosmologies. I met chaos when I saw one of the first pieces. A work that fascinated me, “Tree of Life (In Image of Old Things)” stood tall and colorful. Branches painted yellow, blue, red and pink pointed out in all directions. A black and gold crown rested upright closer to the side of the tree, and the whole tree sat inside of a plant stand made from an old tire. Other materials used included roots, wire, fabric, enamel, and industrial sealing compound.

Although I had a hard time grasping the visual aspect of the work, I immediately resonated with the underlying message of regeneration. Thornton Dial’s use of “old” items to create a fresh piece of art is a reminder that we shouldn’t take the past for granted. I thought of the Race & Racism Project and how we’ve been connecting with alumni who have been in our same shoes. Instead of allowing the lessons that they learned fall by the wayside, it’s helpful to hear their experiences and apply what we can as present-day students.

After having this connection with the “Tree of Life,” my high hopes for the rest of the exhibit were not fulfilled. Across from Dial’s assemblage piece “Tree of Life” was “Housetop,” a quilt assembled by Gee’s Bend quilters. Gee’s Bend, now known as Boykin, is a small and isolated town near Selma, Alabama. Many of these quilters were descendants of enslaved African women who lived in unheated shacks, so they made quilts for sustainability. While the quilts were beautiful and held messages of self-determination, I had a hard time appreciating and understanding them as they were placed throughout Cosmologies. I felt this same frustration as I made my way to another corner of the exhibition and saw a sculpture of an owl next to paintings of birds, hens & chicks, and houses.

To sum it up, I was missing the story. I understood the underlying connection concerning the reuse of material, but I didn’t understand the “why” or the “why is this important.” I was disappointed that these questions were not aptly answered at the exhibit. Though Cosmologies lacked a strong narrative, I appreciated seeing so many nontraditional pieces in one space and the theme of resistance reflected in the work.