by Jenifer Yi

Jenifer Yi is a sophomore from Santa Clarita, California majoring in Biochemistry with a concentration in Neuroscience and a minor in Healthcare Studies. She has been involved with the Race & Racism Project since 2018 and hopes to diversify the conversation and inclusion of all students of color at the University of Richmond. On campus, she is a part of the leadership board for the Asian American Student Union. Through her contributions to the project, she wants to push for campus-wide racial awareness. In the future, she hopes to pursue a career in medicine while continuing to advocate and raise awareness for healthcare access for minorities.

Richmond has a rich history as one of the most active participants in the African slave trade and is prominently known as the Capital of the Confederacy. Despite its history, Richmond’s troubled past is not always visible to the naked eye. Many prominent landmarks have been paved over by sidewalks, parking lots, and contemporary infrastructure. A short car ride from metropolitan Richmond, there are still prominent relics of the Civil War era Virginia that have not fallen to city landscaping. Plantations, which used to be quintessential to the slave trade and economic boom of the South, now stand as echoes of the past. I decided to delve into the history of history of oppressed enslaved Africans by visiting Shirley Plantation, one of several James River plantations.

Richmond has a rich history as one of the most active participants in the African slave trade and is prominently known as the Capital of the Confederacy. Despite its history, Richmond’s troubled past is not always visible to the naked eye. Many prominent landmarks have been paved over by sidewalks, parking lots, and contemporary infrastructure. A short car ride from metropolitan Richmond, there are still prominent relics of the Civil War era Virginia that have not fallen to city landscaping. Plantations, which used to be quintessential to the slave trade and economic boom of the South, now stand as echoes of the past. I decided to delve into the history of history of oppressed enslaved Africans by visiting Shirley Plantation, one of several James River plantations.

Charles City County had a strikingly different landscape from the concrete fortress of Richmond. Tucked away in a midst of a forest, the Shirley Plantation home rests facing the James River, surrounded by acres of farmland. A National Historic Landmark, Shirley Plantation traces its history back to Colonial America when it was created from a 1613 Crown Grant and still houses the descendants of the Hill and Carter families (previous owners of the plantation, John Carter and Elizabeth Hill). I realized that though Shirley had participated in the use of slave labor on its plantation, it held familial history for the living descendants of Civil War era plantation owners. It was and still is a home, as much as it is a relic of American history.

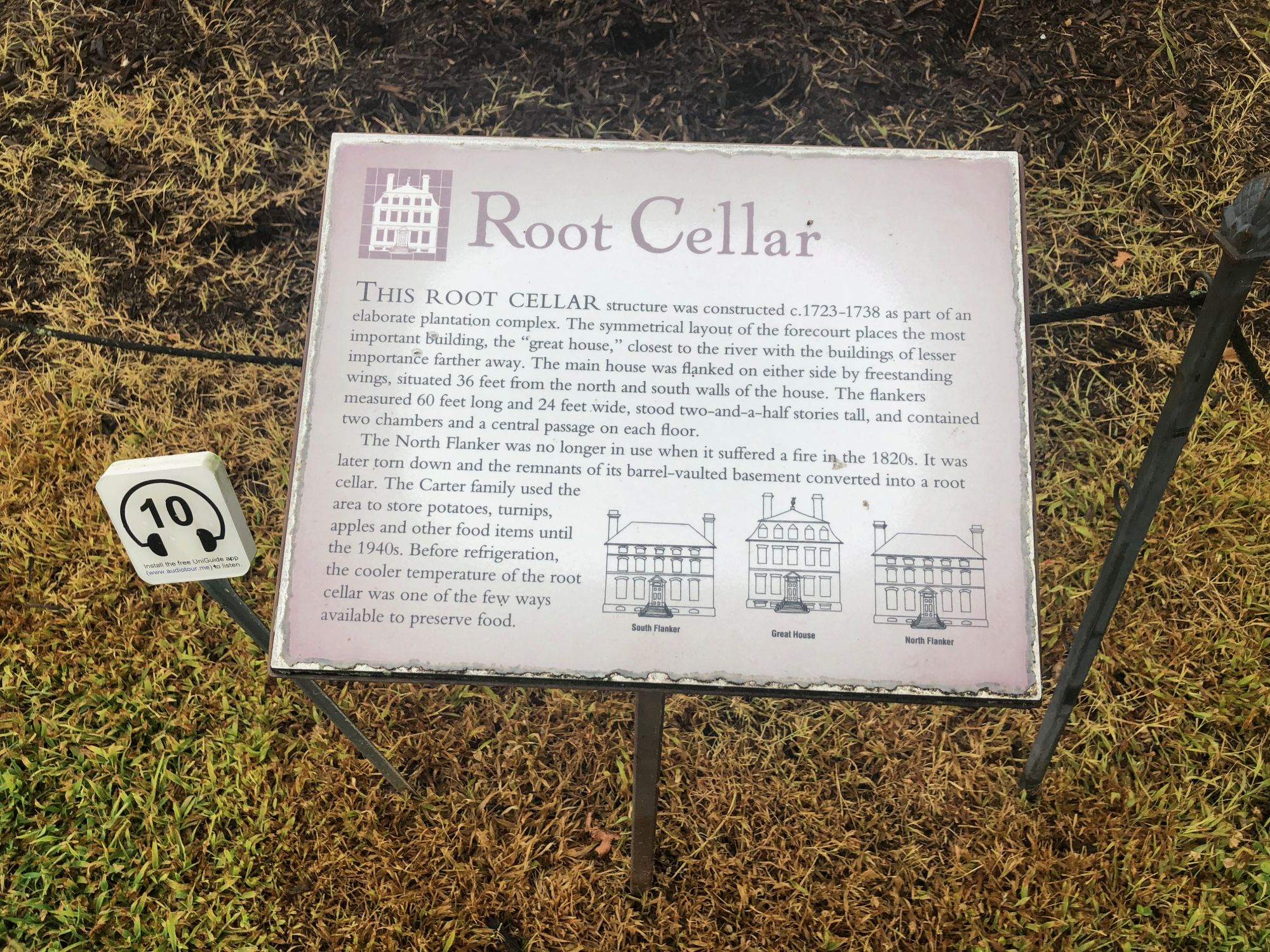

On the walk towards the Shirley home, I noted that many of the buildings utilized by the Hill and Carter families and enslaved people were well-intact, with guests able to access and walk around in many of the structures. Each structure had signs that explained the uses for certain structures and buildings, such as a root cellar utilized for preserving food, a store house, a pump house for obtaining water, a smokehouse, a stable, and an ice cellar among others. There were even benches at the base of a Willow Oak, facing the James River.

On the walk towards the Shirley home, I noted that many of the buildings utilized by the Hill and Carter families and enslaved people were well-intact, with guests able to access and walk around in many of the structures. Each structure had signs that explained the uses for certain structures and buildings, such as a root cellar utilized for preserving food, a store house, a pump house for obtaining water, a smokehouse, a stable, and an ice cellar among others. There were even benches at the base of a Willow Oak, facing the James River.

With its ancient trees, sprawling grass hills, and boasts of architectural and compositional beauty, it was almost difficult for me to imagine enslaved people living and working in this quaint riverside home. I later found out, in a tour of the home, that a slave quarters once stood next to the Shirley house. Oddly enough, this building was not preserved for visitors. It became obvious that this space was not wholly dedicated to remembering and honoring the enslaved people that worked at Shirley Plantation. It was mainly a space for honoring and conserving the memory of those who lived under the roof of a home constructed by those enslaved people.

With its ancient trees, sprawling grass hills, and boasts of architectural and compositional beauty, it was almost difficult for me to imagine enslaved people living and working in this quaint riverside home. I later found out, in a tour of the home, that a slave quarters once stood next to the Shirley house. Oddly enough, this building was not preserved for visitors. It became obvious that this space was not wholly dedicated to remembering and honoring the enslaved people that worked at Shirley Plantation. It was mainly a space for honoring and conserving the memory of those who lived under the roof of a home constructed by those enslaved people.

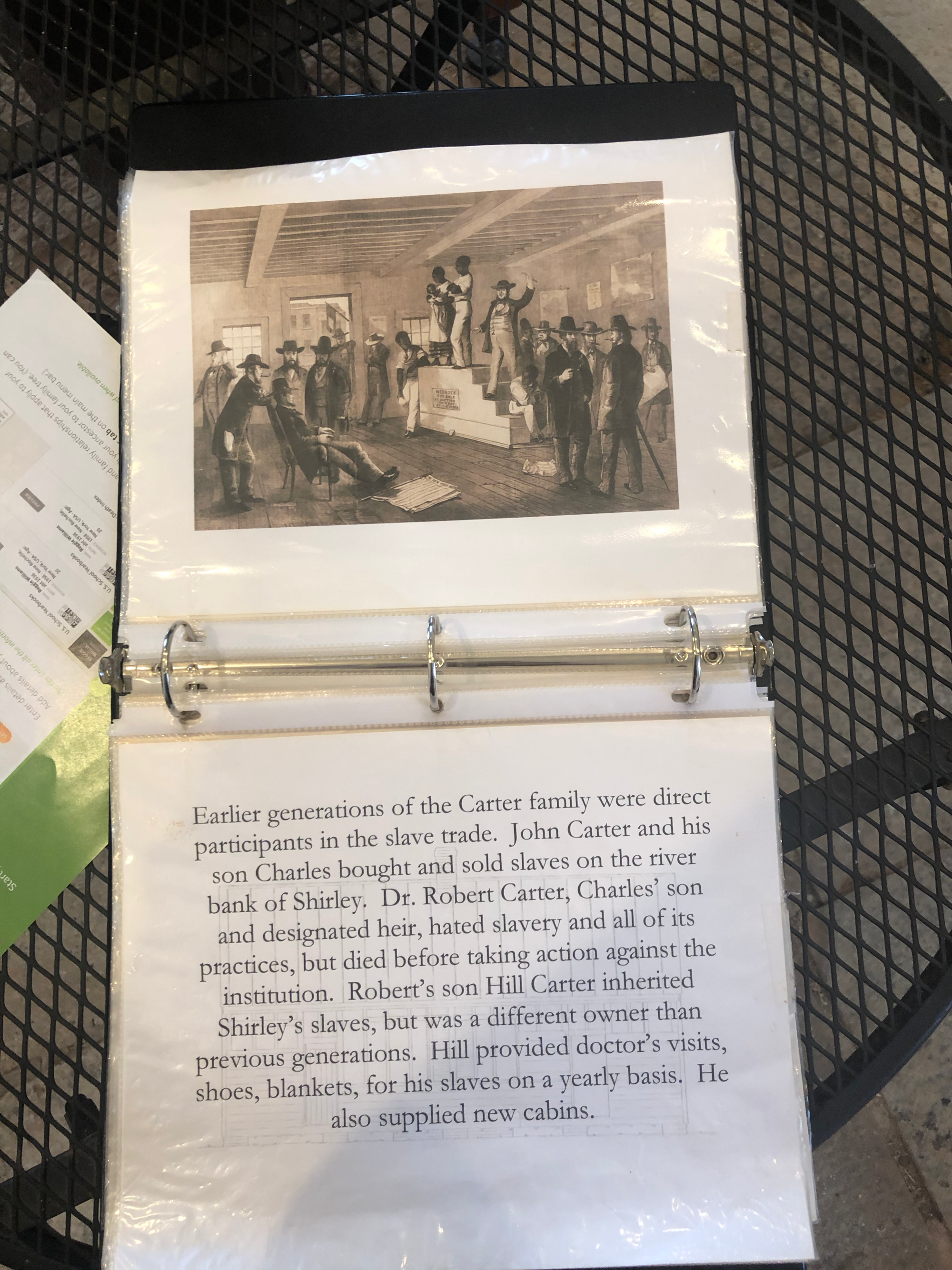

The main focus of the plantation seemed to be preserving the history of the owners of the plantations, but there was a significant spotlight on the roles such as cooking, housekeeping, tending and harvesting crops, and skilled labor such as carpentry, masonry, and blacksmithing that enslaved people played during the history of Shirley Plantation. Reading through a binder in the kitchen exhibit, I discovered an extensive record of how the Carter and Hill families were associated with the slave trade.

I found that the early generations of the owners of the Shirley Plantation were direct participants in the slave trade, and it was interesting how certain descendants of the plantation family received accolades for their humane treatment of slaves. The Shirley Plantation owners were documented to have taught the people they enslaved to read and write, armed African hunters to hunt game, and one member of the Carter family had even written about his distaste for the slave trade. I found myself wondering: Does the acknowledgement of humane treatment make people view the slave trade or the plantation family with less vehemence because they were not treating their slaves as just property?

I felt conflicted. On one hand, the Shirley Plantation lineage was a product of their time – owning and utilizing slave labor was common on plantations – but these enslaved Africans were at the end of the day, slaves with no individual freedom. It is easier for the current owners of Shirley Plantation to distance themselves from their history of association with the slave trade. By trying to uphold the dignity of their family name and lineage by venerating their ancestors, the current generation treads the dangerous line between acknowledging or sugar coating the past. With a lack of perspective from the oppressed and manipulated enslaved Africans, it is difficult to know what the environment at Shirley Plantation was truly like. Therefore, we only hear one side of the story – that of the slave owners.