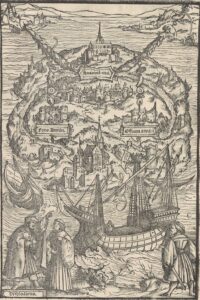

Utopia by Thomas More, 1518.

Have you ever been disappointed by the city you live in? Have you ever dreamed of living in a perfect city? A place you can find beautiful gardens on every street corner? Where every neighbor is your friend? Ever since the ancient Greeks lived in “Polis”, man has been dreaming of a perfect city. This image has gone through multiple transformations as civilization changes and is now widely known as “the Utopia”. The name “Utopia” comes from the Greek words “eu – topos” and “ou – topos”, which mean “good place” and “no place”. The name itself implies Utopia is never a realistic urban planning scheme but an idealistic and humanistic hope. As a voice of the Renaissance, the word “Utopia” was first addressed by Sir Thomas More as the title of his book, which created not only a city but an entire state. More’s utopia, as a prototype of all utopia images afterward, is designed in homage to classical Greek city states in many aspects and also incorporated the European scene in his time. Today, the Utopia is still an incredible bequest for urban planners and social reformers.

Utopia’s aims in urban design were to bring its inhabitants security and happiness. Security came from the walls and from the political structure they contained; happiness from the subtle blending of rural and urban elements in a pleasant design. The city regions formed the basis of the island, surrounded by a circle of rural areas of “share houses or farms well appointed and furnished with all sorts of instruments belonging to husbandry”. Rural and urban societies were fully integrated by the system of rotating labor groups that annually 20 rural residents come to the city for service and are replaced by citizens after 2 years. The rotation between city life and country life implies More’s political ambition for an equal society where everyone fully participates in public life and contributes to the nation.

The capital city of Utopia is named Amaurotum, the “darkling city”, “city of clouds”. Amaurotum is nevertheless a city of gardens. Every house there looks alike and is enclosed by a large garden. “More makes sure of his garden city by educating garden citizens.” As a crucial component of city life, the Utopian citizens were encouraged and praised for growing vines, fruits, herbs, and flowers. “Their studies and diligence come not only of pleasure but also of certain strife and contention that is between strete and strete, concerning the trimming, husbanding, furnishing of their gardens: every man for his own part.” More has treated gardening as an important component of public affairs through which citizens of Utopia get educated and civilized.

One particular feature of Amaurotum that might confuse you is that it contains no private space. In the perfect city in More’s view, no distinctions are made between public and private space. “Doors are always open”. Constant participation and confrontation with public life is not an option but an imperative. Each city is around 24 miles from the other and can be reached on foot in a day. A perfect society in More’s view shall cultivate its citizens into perfect human beings. There would be no more disagreements, every person could coexist harmoniously. Such a city is in need of no change, only expansion. When the demographic maximum capacity is reached in a city, people leave the original site and build a new yet identical one.

Despite the perfection More made to the city, traces of 16th-century London could be found everywhere in Amaurotum. More was born and raised in London. It’s claimed by his friend Erasmus that it’s More’s intention to create his dream city based on his homeland. Utopia is noted to be two hundred miles wide, equivalent to the breadth of England in the Saint Albans Chronicle, published in 1515. And the Utopian channel is very likely derived from the English Channel, which More has traveled across several times to visit the continent. The number of urban regions in Utopia is 54, very close to the amount of administrative units in the mid 16 century England. The idea of an isolated island itself may come from the unique geography of England. The 15-16 century European environment in which More lived hasn’t yet possessed any organized form of modern cities. “They existed by the sheer juxtaposition of houses and their connection with the streets or squares. It was a pure topological distribution.” As a patriot, it might have been a wish of More’s to realize his plan for Utopia in England one day.

As it is portrayed on the map, Utopia is an isolated island distant from human civilization, a completed garden of Eden where no reformation or revolution would ever take place. The citizens don’t need to cope with the complexity and unpredictability of everyday life. This imaginary scheme originated from his idealistic view of humanity that if well taught, all man could possess virtue and morality. As a modern audience, would you agree with More’s idealistic idea about humanity? Or would there be untamable demons lying beneath which nowhere even the Utopia could calm?

You must have noticed that the map itself looks quite different from typical maps we’re familiar with. There’s no data or measurement, only a few descriptions… Actually the “map” is a picture of Utopia’s front matter. Sir More intentionally used a map as his book cover, which was quite an innovation at his time. And this tradition has been inherited throughout the multiple editions of Utopia til now. A couple of modern version of the Utopia map is exhibited below. The ongoing updating of Utopia vision serves as a perspective for us to see not only Sir More’s philosophy for a perfect city, but also the ideas of people who lived in different times, different areas of the world, and different cultures.

Blog link: https://caseyhandmer.wordpress.com/

Atlas:

Map of Narnian world as described in The Chronicles of Narnia by C.S. Lewis

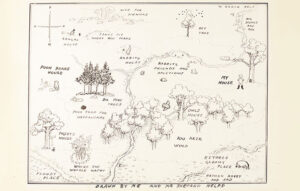

The original map of the hundred acre wood, published in the opening end-papers of the 1926 first edition of Winnie-the-Pooh

I would like to introduce a couple more maps showing people’s fantasies about the worlds they want to live in. The map of Winnie the Pooh and The Chronicles of Narnia both created a world for children to explore different possibilities outside everyday life and modern civilization. They’re certainly much less organized than Utopia, nevertheless, the creativity and hope for a better world are consistent.

Reference:

Hutchinson, S. (1987). Mapping Utopias. Modern Philology, 85(2), 170–185. http://www.jstor.org/stable/437184

J. Rawson Lumby, edit.: Utopia (Cambridge, 1883); Edward Surtz and J. H. Hexter, edits.: The Complete Works of St. Thomas More: Volume 4, Utopia (New Haven, 1965). The text of this latter work is also included in a paperback edition, Edward Surtz (edit.): St. Thomas More: Utopia (New Haven, 1964).

Lewis Mumford, The City in History (New York, 1961), p. 325.3

Goodey, B. R. (1970). Mapping “Utopia”: A Comment on the Geography of Sir Thomas More. Geographical Review, 60(1), 15–30. https://doi.org/10.2307/213342

J. Rawson Lumby, edit.: Utopia (Cambridge, 1883); Edward Surtz and J. H. Hexter, edits.: The Complete Works of St. Thomas More: Volume 4, Utopia (New Haven, 1965). The text of this latter work is also included in a paperback edition, Edward Surtz (edit.): St. Thomas More: Utopia (New Haven, 1964), p. 75

“The Descrypcon of Englande” is included at the end of “Cronycle of Englande….by one sometyme scole mayster of St. Albans (London, 1515).

Erwin A. Gutkind: Urban Development in Central Europe, 1964, p. 176.

To start off, great job on bringing this map to us, Moyan. What strikes me as intriguing is the Greek etymology of utopia. Utopia’s Greek origin, coupled with the influence of European thinkers, has developed utopia into just that; European idealism. This relates to a key concept we have learned in Rhetorical Lives of Maps; the map, or in this case, the word, makes a proposition, that is biased by those making the map and the audience the mapmaker wants to relate to. The concept of utopia has been intrinsically associated with European opinions on what the ideal society, and forwarded towards European audiences.

Remaining on that point of maps being propositional, you have provided us with information that affirms just how much the propositions, ones that maps attempt to assert as fact, are subjective in nature and influenced heavily by the background and intentions of the mapmaker and their audience. As you noted, More’s vision of utopia took great influence from his home of Britain and his personal opinions on what the ideal existence of humanity should be like. More’s map asserts that ‘this is what Utopia is!’ In reality, it’s what he wanted it to be.