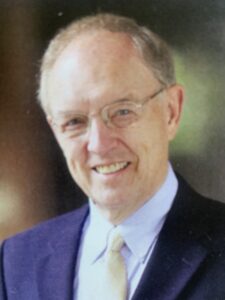

If you ask anyone acquainted with the Rev. Dr. David Burhans, they’ll smile and tell you that he was among the most beloved individuals they’ve ever known. Generations of Richmond alumni would surely consider Burhans to be a cherished iconic figure, the spiritual face of the University of Richmond. Even the briefest encounter with Burhans left people feeling valued and loved, and certainly moved, at the deepest level of their being.

I knew David Burhans for almost 40 years as a friend, colleague, and one of his parishioners. Thousands of Richmond students, alumni, staff, and faculty were fashioned into better people because of David’s influence. I don’t claim to have been among David’s closest friends. What I do know is that he left an indelible impact on my life and on the lives of countless people who had the pleasure of knowing him.

What was the key to David Burhans’ enduring and positive impact on the world? From my experiences with him and from his own writings, here are 12 principles that he lived by and cultivated in all of us:

- Look at the world with a sense of wonder and awe. David enjoyed quoting American poet Mary Oliver’s belief that we are all born to “to look, to listen.” The famed Rabbi Abraham Heschel used the term radical amazement to describe the practice of remaining present and aware of the small miracles that abound in every moment. David reminded us that Heschel didn’t ask God for success, but only for wonder. “Looking back over more than seven decades,” wrote David, “mindfulness and wonder capture the essence of my spiritual and professional journey.” David’s ministry was “an exercise in looking, listening and instruction.”

- We are called to answer three important spiritual questions. In reflecting on his career, David wrote: “This personal journey began with a profound sense of awe and wonder prompting a fresh consideration of three great spiritual questions I had contemplated through college and graduate school. Who am I? Why am I here? What difference can I make?” For David, “it was about the human search for meaning and purpose.” He made these three questions the major focus for the University Chaplaincy, and he believed that “every well-educated person is expected to consider” the meat and marrow of these questions.

- We find a safe and welcoming place to discuss life’s meaning and purpose. David’s vision of the Chaplaincy was that it “would contribute to an atmosphere of openness and acceptance in the community and become a place at the heart of the campus which would encourage a free exchange of ideas, become a safe place to ask questions, and help initiate faith in ‘seekers’ of purpose and meaning.” David’s goal was to create a sacred space for people “to discuss personal issues, share grief experiences, celebrate joys and achievements, and a place to examine and strengthen one’s own faith perspective.” Thanks to David, and his successors including current Chaplain Craig Kocher, the Office of the Chaplaincy provides opportunities for members of the Richmond community to enhance their spiritual, emotional, and social well-being within a welcoming inter-religious context.

- A loving Higher Power guides us on the journey toward becoming our best selves. David believed that the God of our understanding was always a “Living God” of love, compassion, and healing. He wrote: “I felt strongly that I was on an educational pilgrimage with the students, on a professional journey of personal growth with faculty, staff and administrators, on a daily, demanding sojourn with University families like my own who welcomed support and encouragement.” David’s own personal spiritual journey involved “a public declaration of faith and trust in the Living God [and] ultimately a compelling desire to proclaim the Love of God. And what does the Lord require of you but to do justice, to love kindness and to walk humbly with your God.”

- We engage in practices that improve our conscious contact with God. David often shared personal “experiences of what I can only describe as divine encounters or intimations of the Holy — moments of profound gratitude, insight, guidance, wonder upon wonder.” David often expressed his amazement “at the strength that we humans have to live with heartache, disappointment, and loss and the courage that people have to keep on in the face of difficult odds and pain and suffering.” For David, “there is life beyond the tragedies that we experience.” David’s spiritual practices were prayer, wonder, gratitude, loving kindness, an unshakeable faith and enduring optimism that no matter what adversity we face, all is well.

- We remember that gratitude, compassion, and humility are the greatest of all virtues. “A profound spiritual truth I strongly embraced,” wrote David, is that “Life is a gift: handle this journey with gratitude, with compassion, with humility.” David quoted the ancient Roman philosopher Cicero: “Gratitude is not only the greatest of all virtues but the parent of all others.” Compassionate connection with fellow humans – “listening with awareness and creating a culture of caring” — give renewed hope and new meaning to our journey. For David, the gift of humility is critical. Theologian Reinhold Niebuhr urged us to constantly examine our actions and never be too certain of our own virtue. David believed “it was important that the ministry have people who are not holier than thou types — just normal, regular people who love athletics, have hobbies and a real appreciation for the breadth of life and who are curious and always interested in learning new things.”

- We treat all people with congruence, empathy, and respect. A student of psychology, David admired the humanistic, positive psychological approach to understanding humanity. One of the founding humanists, Carl Rogers, embraced the idea that all human relationships are forged with congruence, empathy, and Rogers described congruence as being genuine and honest with others, reflecting a person’s sincerity, integrity, and authenticity. David believed that an individual’s life work should be “within a stone’s throw of his pronouncements and proclamations.” The second virtue, empathy, is the ability to feel what others feel. And respect refers to an unconditional positive regard for all other people. For David, “These qualities immediately identified spiritual leadership at its best,” and he developed these social skills better than any person I’ve ever known.

- Cultivating relationships with others is the key to a vibrant spiritual life. “All relationships are sacred,” David told me, more than once. David was skillful in the heartful art of human connection. What was his secret? He made developing and nurturing human relationships his top priority. As University Chaplain, he was gifted in ministering to “an intergenerational community of people (students, faculty, staff, administration) with diverse social, economic and religious or non-religious backgrounds and perspectives.” David sought to integrate the “body, mind and spirit so as to counter the fragmentation of knowledge, learning and human development.” His Chaplaincy accomplished this goal “by conjoining the love of God and the love of learning in the flesh, in the human flesh of persons—persons in the Chaplaincy, persons in the faculty and staff, and persons among the student body.”

- Keeping an open mind and an open heart will heal and unify us all. My own research on heroism has shown that our greatest heroes always direct their energies toward healing and unifying people. David Burhans “approached life, work and relationships in the academy with a more open mind and heart—not open without any fixed point, but open and receptive to new ideas and ways of engaging a diverse community of people.” He recognized that love, compassion, and embracing the multiplicity of humanity were essential qualities for the Chaplaincy.”

David’s proudest moments resided in the Chaplaincy’s openness to interfaith dialogue and welcoming students of all demographies, including students of every faith commitment and sexual orientation. David wrote, “I was asked to be the Chaplain to all the students, faculty, and staff at the University of Richmond. Every one of these people is welcome at this University and in this Chaplaincy office, and I embrace them.” David made it a priority to “break down barriers that divide us, to broaden our world view, reaching beyond our own kind, our own country, our own religious creed.” As a Christian, David was open and humble in welcoming and acknowledging “that our brothers and sisters of other religious traditions surely have a word from God for us to hear.”

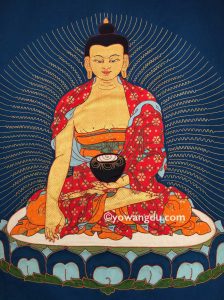

David’s proudest moments resided in the Chaplaincy’s openness to interfaith dialogue and welcoming students of all demographies, including students of every faith commitment and sexual orientation. David wrote, “I was asked to be the Chaplain to all the students, faculty, and staff at the University of Richmond. Every one of these people is welcome at this University and in this Chaplaincy office, and I embrace them.” David made it a priority to “break down barriers that divide us, to broaden our world view, reaching beyond our own kind, our own country, our own religious creed.” As a Christian, David was open and humble in welcoming and acknowledging “that our brothers and sisters of other religious traditions surely have a word from God for us to hear.” - The Higher Power of our understanding loves and affirms us at all times. David held the steadfast belief that “there has been and continues to be a presence of something far greater than I can comprehend which loves and affirms me.” He knew that this Living God was a central part of each person’s life, whether they knew it or not. When the Wilton Center was built, he arranged for “a signature piece of art to be placed on exhibit… symbolizing a person’s journey toward wholeness through education, personal faith, and service to others.” David’s father, Dr. Rollin S. Burhans, articulated the goal of the Jessie Ball duPont Chaplaincy and its objective of bringing “wholeness to fragmented, fragile lives by the integrating, life-changing power of Thy Love.”

- A sense of humor can enrich life and build bonds. David would often remark that “laughter is the shortest distance between two people.” As such, he brought humor and joy to the Chaplaincy at Richmond. He wrote, “I think humor is one of those key characteristics of a minister — that you not take yourself too seriously and be able to laugh at yourself and with others.” Research by psychologists Laura Kurtz and Sara Algoe confirms what David intuitively knew, namely, that humor brings people together and acts as a “social glue” that builds loving, trustful bonds.

- Wonder is in pursuit of us. This is one of David’s keenest insights: “I am bold to suggest that anyone who is attune to moral and spiritual values, who is seeing and listening and paying attention will likely understand that Wonder just might be another name for God.” For David, the allure of living a rich, spiritual life was not a one-sided affair: If human beings are seeking the transcendent, the transcendent is also seeking us. The “Ultimate Truth,” said David, is not just that we pursue Wonder but that “Wonder is in pursuit of us! This all-encompassing Spirit of awe and wonder, love and grace is loose upon the world, a force over which we humans have little if any control. We can, however, be used by it!”

–

Those of us who were fortunate enough to have known and loved David Burhans will never forget his spark of life, his wisdom, his tender and generous loving spirit. David knew that despite our fragmented world, “we are creatures of relatedness who grow, mature and fulfill our own destinies through nurturing and challenging relationships.” He called his own journey “a journey of thanksgiving, compassion, laughter, and community.” That David took a warm, deep interest in each person he met is proof that Wonder is pursuing us, and that we are called to pass on this wonderous spirit to others. There’s no better way to honor David Burhans than to live our lives the way he lived his – with his boundless, effervescent joy, wonder, and love.

References

Brockwell, P. (2015). David Burhans’ exit interview. Retrieved from https://urnow.richmond.edu/magazine/article/-/12804/exit-interview.html

Burhans, R. (1986). Prayer of dedication. Worship celebration and dedication of The Jessie Ball duPont Chair of the Chaplaincy, Cannon Memorial Chapel, University of Richmond, October 19th.

Burhans, D. (2016). The pursuit of wonder. In S. T. Allison, C. T. Kocher, & G. R. Goethals (Eds), Frontiers in spiritual leadership: Discovering the better angels of our nature. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Heschel, A. J. (1983). I asked for wonder: A spiritual anthology. New York: The Crossroad Publishing Co.

Kurtz, L., & Algoe, S. (2015). Putting laughter in context. Personal Relationships, 22, 573-590.

Oliver, M. (2004). Mindful. Why I wake early. Boston: Beacon Press.

By Dick Mercer

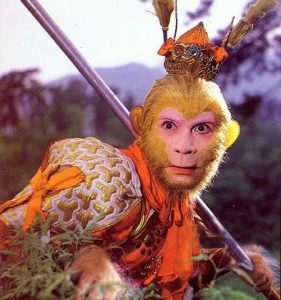

By Dick Mercer Tripitaka says they must be cautious as there might be danger here; Monkey responds, “Master, you should relax and not worry.”

Tripitaka says they must be cautious as there might be danger here; Monkey responds, “Master, you should relax and not worry.” So, freshly taught, the pilgrims set out again for China with the newly inscribed scrolls.

So, freshly taught, the pilgrims set out again for China with the newly inscribed scrolls. The members of the dharma posse are attending him when he starts his recitation, but just as he begins, they are all miraculously lifted into the air and transported back to the presence of the Buddha in India where each is rewarded with an appropriate title. Perhaps best of all the terrible little migraine cap used to control Monkey when he gave in to bad temper and anger is removed. It is no longer necessary.

The members of the dharma posse are attending him when he starts his recitation, but just as he begins, they are all miraculously lifted into the air and transported back to the presence of the Buddha in India where each is rewarded with an appropriate title. Perhaps best of all the terrible little migraine cap used to control Monkey when he gave in to bad temper and anger is removed. It is no longer necessary. By Dick Mercer

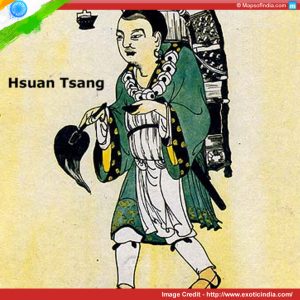

By Dick Mercer The story of Hsuan-tsang is very different. An orphan found floating in a basket down a river, he is taken in and raised as a Monk at Hung-Fu Buddhist temple in the imperial capital Ch’ang-an. As was the case with the Jade Emperor of heaven struggling with Monkey, the mortal Tang emperor is embroiled in troubles that literally take him to hell and back burdened with a heavy obligation to sponsor a grand religious ceremony. He selects Hsuan-tsang to celebrate these rites.

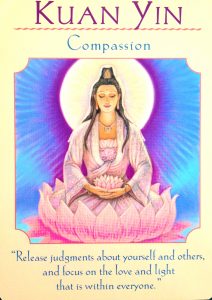

The story of Hsuan-tsang is very different. An orphan found floating in a basket down a river, he is taken in and raised as a Monk at Hung-Fu Buddhist temple in the imperial capital Ch’ang-an. As was the case with the Jade Emperor of heaven struggling with Monkey, the mortal Tang emperor is embroiled in troubles that literally take him to hell and back burdened with a heavy obligation to sponsor a grand religious ceremony. He selects Hsuan-tsang to celebrate these rites. Kuan-Yin to join the pilgrimage in exchange for freedom from bondage. It soon is obvious to the new members, however, that Monkey is by far the most powerful member of the group. In fact, Pigsy asks Monkey why doesn’t he simply carry them all to India in an instant and so avoid all the hard work and dangers that surely lie in front of them.

Kuan-Yin to join the pilgrimage in exchange for freedom from bondage. It soon is obvious to the new members, however, that Monkey is by far the most powerful member of the group. In fact, Pigsy asks Monkey why doesn’t he simply carry them all to India in an instant and so avoid all the hard work and dangers that surely lie in front of them.