By Scott T. Allison and Gwendolyn C. Setterberg

By Scott T. Allison and Gwendolyn C. Setterberg

“Hardships prepare ordinary people for an extraordinary life.” – C.S. Lewis

This article is excerpted from:

Allison, S. T., & Setterberg, G. C. (2016). Suffering and sacrifice: Individual and collective benefits, and implications for leadership. In S. T. Allison, C. T. Kocher, & G. R. Goethals (Eds), Frontiers in spiritual leadership: Discovering the better angels of our nature. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Are pain and suffering destructive experiences to be avoided, or are they opportunities for people to develop an extraordinary life? The wisdom of spiritual philosophies throughout the ages has converged with modern psychological research to produce an answer: Suffering and sacrifice offer profound gains, advantages, and opportunities to those open to such boons.

Our review of the wisdom gleaned from theology and psychology reveals at least six beneficial effects of suffering. These include the idea that suffering (1) has redemptive qualities, (2) signifies important developmental milestones, (3) fosters humility, (4) elevates compassion, (5) encourages social union and action, and (6) provides meaning and purpose.

1. Suffering is Redemptive

Buddhism teaches us that suffering is inevitable but can also be a catalyst for personal and spiritual growth. The Buddha cautioned that the desire for enlightenment and awakening asks much from those who seek it. One must turn toward the  suffering to conquer it. Buddhists redeem themselves by channeling the full energy of their attachments to the physical world – the cause of all suffering – into compassionate concern for others.

suffering to conquer it. Buddhists redeem themselves by channeling the full energy of their attachments to the physical world – the cause of all suffering – into compassionate concern for others.

Christianity also embraces the redemptive value of suffering. Foremost in the Judeo-Christian tradition is the idea that all human suffering stems from the fall of man (Genesis 1:31). The centerpiece of suffering in the New Testament is, of course, the portrayal of the passion of Christ through the Synoptic Gospels. For Christians, Christ’s suffering served the purpose of redeeming no less than the entire human race, elevating Jesus into the role of the Western world’s consummate spiritual leader for the past two millennia.

Our previous work on the psychology of heroism has identified personal transformation through struggle as one of the defining characteristics of heroic leadership. Nelson Mandela, for example, endured 27 years of harsh imprisonment before assuming the presidency of South Africa. Mandela’s ability to prevail after such long-term suffering made him an inspirational hero worldwide. Desmond Tutu opined that Mandela’s suffering “helped to purify him and grow the magnanimity that would become his hallmark”.

In the field of positive psychology, scholars have acknowledged the role of suffering in the development of healthy character strengths. Positive psychology recognizes beneficial effects of suffering through the principles of posttraumatic growth, stress-related growth, positive adjustment, positive adaptation, and adversarial growth.

A study of character strengths measured before and after the September 11th terrorist attacks showed an increase in people’s “faith, hope, and love”. The redemptive development of hope, wisdom, and resilience as a result of suffering is said to have contributed to the leadership excellence of figures such as Helen Keller, Aung San Suu Kyi, Mahatma Gandhi, Malala Yousafzai, Stephen Hawking, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Shiva Nazar Ahari, Oprah Winfrey, J. K. Rowling, and Ludwig van Beethoven, among others.

2. Suffering Signifies a Necessary “Crossover” Point in Life

Psychologists who study lifespan development have long known that humans traverse through various stages of maturation from birth to death. Each necessary entanglement on the human journey represents painful progress toward becoming fully human, each struggle an opportunity for people to achieve the goal of wholeness. According to Erik Erikson, people must successfully negotiate a specific crisis associated with each growth stage. If mishandled, the crisis can produce suffering, and it is this suffering produces the necessary motivation for progression to the subsequent stage.

Erikson was the first psychologist to describe the causes and consequences of the “midlife crisis”. According to Erikson, middle-aged people often struggle to find their purpose or meaning in life, particularly after their children have left the home. The only way to move forward is to carve out a life of selfless generativity. A  generative individual is charitable, communal, socially connected, and willing to selflessly better society. Generativity is the only antidote to the midlife crisis. Generative individuals are among society’s most valuable human assets; they are often called the elders or heroes of society.

generative individual is charitable, communal, socially connected, and willing to selflessly better society. Generativity is the only antidote to the midlife crisis. Generative individuals are among society’s most valuable human assets; they are often called the elders or heroes of society.

A recurring theme in world literature is the idea that people must plummet to physical and emotional depths before they can ascend to new heights. In The Odyssey, the hero Odysseus descends to Hades where he meets the blind prophet Tireseas. Only at this lowest of points, in the depths of the underworld, is Odysseus given the gift of insight about how to become the wise ruler of Ithaca. The Apostles’ Creed tells of Jesus descending into hell before his ascent to heaven. Somehow, the author(s) of the creed deemed it absolutely necessary for Jesus to fall before he could “rise” from the dead.

In eastern religious traditions, such as Hinduism, one encounters the idea that suffering follows naturally from the commission of immoral acts in one’s current or past life. This type of karma involves the acceptance of suffering as a just consequence and as an opportunity for spiritual progress.

The message is clear: we must die, or some part of us must die, before we can live, or at least move forward. If we resist that dying – and most every one of us does – we resist what is good for us and hence bring about our own suffering. Psychoanalyst Carl Jung observed that “the foundation of all mental illness is the avoidance of true suffering.”

Paradoxically, if we avoid suffering, we avoid growth. People who resist any type of dying will experience necessary suffering. Those who resist suffering are ill equipped to serve as the leaders of society. Our most heroic leaders, like Nelson Mandela, have been “through the fire” and have thus gained the wisdom and maturity to lead wisely.

3. Suffering Encourages Humility

Spiritual traditions from around the world emphasize that although life can be painful, a higher power is at work using our circumstances to humble us and to shape us into what he, she, or it wants us to be. C.S. Lewis once noted, “God whispers to us in our pleasures, speaks to us in our conscience, but shouts in our pains: It is His megaphone to rouse a deaf world.” Richard Rohr opines that suffering “doesn’t accomplish anything tangible but creates space for learning and love.” Suffering serves the purpose of humbling us and waking us from the dream of self-sufficiency.

Humility is a major step toward “recovery” in twelve-step programs such Alcoholics Anonymous, Overeaters Anonymous, Gambler’s Anonymous, and Al-Anon. Step 1 asks participants in these programs to admit their total powerlessness over their addiction. The spiritual principle at work here is the idea that victory is only possible through admitting defeat. Richard Rohr argues that only when people reach the limits of their private resources do they become willing to tap into the “ultimate resource” – God, Allah, the universe, or some power greater than themselves.

programs to admit their total powerlessness over their addiction. The spiritual principle at work here is the idea that victory is only possible through admitting defeat. Richard Rohr argues that only when people reach the limits of their private resources do they become willing to tap into the “ultimate resource” – God, Allah, the universe, or some power greater than themselves.

In twelve-step programs, pain, misery, and desperation become the keys to recovery. Step 7 asks program members to “humbly ask God” to remove personal defects of character (italics added). This humility can only be accomplished by first admitting defeat and then accepting that one cannot recover from addiction without assistance from a higher power. In the end, selflessly serving others – Step 12 — is pivotal in maintaining one’s own sobriety and recovery.

4. Suffering Stimulates Compassion

Suffering also invokes compassion for those who are hurting. Every major spiritual tradition emphasizes the importance of consolation, relief, and self-sacrificial outreach for the suffering. Buddhist use two words in reference to compassion. The first is karuna, which is the willingness to bear the pain of another and to practice kindness, affection, and gentleness toward those who suffer. The second term is metta, which is an altruistic kindness and love that is free of any selfish attachment.

Biblical references to compassion abound. According to James 1:27, “Religion that is pure and undefiled before God, the Father, is this: to visit orphans and widows in their affliction.” In Mark 6:34: “When he went ashore he saw a great crowd, and he had compassion on them,  because they were like sheep without a shepherd. And he began to teach them many things.” For Jesus, compassion for the poor, the sick, the hungry, the unclothed, the widowed, the imprisoned, and the orphaned was at the core of his heroic leadership.

because they were like sheep without a shepherd. And he began to teach them many things.” For Jesus, compassion for the poor, the sick, the hungry, the unclothed, the widowed, the imprisoned, and the orphaned was at the core of his heroic leadership.

Psychologists have found that just getting people to think about the suffering of others activates the vagus nerve, which is associated with compassion. Having people read uplifting stories about sacrifice increases empathy to the same degree as various kinds of spiritual practices such as contemplation, prayer, meditation, and yoga. Being outside in a beautiful natural setting also appears to encourage greater compassion. Feelings of awe and wonder about the universe and the miracle of life can increase both sympathy and compassion.

Being rich and powerful may also undermine empathic responses. In a series of fascinating studies, researchers observed the behavior of drivers at a busy four-way intersection. They discovered that drivers of luxury cars were more likely to cut off other motorists rather than wait their turn at the intersection. Luxury car drivers were more likely to speed past a pedestrian trying to use a crosswalk rather than let the pedestrian cross the road. Compared to lower and middle-class participants, wealthy participants also showed little heart rate change when watching a video of children with cancer.

These data suggest that more powerful and wealthy people are less likely to show compassion for the less fortunate than are the weak and the poor. Heroic leaders are somehow able to guard against letting the power of their position compromise their values of compassion and empathy for the least fortunate.

5. Suffering Promotes Social Union and Collective Action

Sigmund Freud wrote, “We are never so defenseless against suffering as when we love, never so forlornly unhappy as when we have lost our love object or its love.” It is clear that Freud viewed social relations as the cause of suffering. In contrast, the spiritual view of suffering reflects the opposite position, namely, that suffering is actually the cause of our social relations. Suffering brings people together and is much better than joy at creating bonds among group members.

Psychologist Stanley Schachter told his research participants that they were about to receive painful electric shocks. Before participating in the study, they were asked to choose one of two waiting rooms in which to sit. Participants about to receive shocks were much more likely to choose the waiting room with people in it compared to the empty room. Schachter concluded that misery loves company.

Schachter then went a step further and asked a different group of participants, also about to receive the shocks, if they would prefer to wait in a room with other participants who were about to receive shocks, or a room with participants who would not be receiving shocks. Schachter found that participants about to receive shocks much preferred the room with others who were going to share the same fate. His conclusion: misery doesn’t love any kind of company; misery loves miserable company.

Effective leaders intuitively know how to use suffering to rally people behind a cause. This leadership skill can be used to achieve evil ends, as  when Adolf Hitler roused the German people to action after their nation suffered from the aftermath of the first world war. Leadership that uses suffering to achieve a moral or higher purpose can be said to be heroic leadership. Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt were masters at capitalizing on the suffering of British and American citizens to bolster resilience and in-group morale. Suffering can be the glue that binds and heals after everything has seemingly shattered.

when Adolf Hitler roused the German people to action after their nation suffered from the aftermath of the first world war. Leadership that uses suffering to achieve a moral or higher purpose can be said to be heroic leadership. Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt were masters at capitalizing on the suffering of British and American citizens to bolster resilience and in-group morale. Suffering can be the glue that binds and heals after everything has seemingly shattered.

Suffering can also mobilize people. The suffering of impoverished Americans during the Great Depression enabled Franklin Roosevelt to implement his New Deal policies and programs. Later, during World War II, both he and Churchill cited the suffering of both citizens and soldiers to promote the rationing of sugar, butter, meat, tea, biscuits, coffee, canned milk, firewood, and gasoline.

In North America, African-Americans were subjugated by European-Americans for centuries, and from this suffering emerged the heroic leadership of Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Jesse Jackson, among others. The suffering of women inspired Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and a host of other heroic activists to promote the women’s suffrage movement.

6. Suffering Instills Meaning and Purpose

The sixth and final benefit of suffering resides in the meaning and purpose that suffering imparts to the sufferer. Many spiritual traditions underscore the role of suffering in bestowing a sense of significance and worth to life. In Islam, the faithful are asked to accept suffering as Allah’s will and to submit to it as a test of faith. Followers are cautioned to avoid questioning or resisting the suffering; one simply endures it with the assurance that Allah never asks for more than one can handle.

For Christians, countless scriptural passages emphasize discernment of God’s will to gain an understanding of suffering or despair. Suffering is endowed with meaning when it is attached to a perception of a divine calling in one’s life or a belief that all events can be used to fulfill God’s greater and mysterious purpose.

Friedrich Nietzche once observed that “to live is to suffer, to survive is to find some meaning in the suffering”. Psychiatrist and concentration camp survivor Viktor Frankl suggested that a search for meaning  transforms suffering into a positive, life-altering experience: “In some way, suffering ceases to be suffering at the moment it finds a meaning, such as the meaning of a sacrifice…. That is why man is even ready to suffer, on the condition, to be sure, that his suffering has a meaning” (145). It appears that the search for meaning not only alleviates suffering; the absence of meaning can cause suffering.

transforms suffering into a positive, life-altering experience: “In some way, suffering ceases to be suffering at the moment it finds a meaning, such as the meaning of a sacrifice…. That is why man is even ready to suffer, on the condition, to be sure, that his suffering has a meaning” (145). It appears that the search for meaning not only alleviates suffering; the absence of meaning can cause suffering.

The ability to derive meaning from suffering is a hallmark characteristic of heroism in myths and legends. Comparative mythologist Joseph Campbell (1949) discovered that all great hero tales from around the globe share a common structure, which Campbell called the hero monomyth. A key component of the monomyth is the hero’s ability to endure suffering and to triumph over it. Heroes discover, or recover, an important inner quality that plays a pivotal role in producing a personal transformation that enables the hero to rise about the suffering and prevail.

Suffering is one of many recurring phenomena found in classic hero tales. Other phenomena endemic to hero tales include love, mystery, eternity, infinity, God, paradox, meaning, and sacrifice. Richard Rohr calls these phenomena transrational experiences. An experience is considered transrational when it defies logical analysis and can only be understood (or best understood) in the context of a good narrative. We can better understand the underlying meaning of suffering within an effective story.

The legendary poet William Wordsworth must have been intuitively aware of the transrational nature of suffering, sacrifice, and the infinite when he penned the following line: “Suffering is permanent, obscure and dark, and shares the nature of infinity.” Joseph Campbell connected the dots between suffering and people’s search for meaning. According to Campbell, the hero’s journey is “the pivotal myth that unites the spiritual adventure of ancient heroes with the modern search for meaning.”

Conclusion

For an individual or a group to move forward or progress, something unpleasant must be endured (suffering) or something pleasant must be given up (sacrifice). Humanity’s most effective and inspiring leaders have sustained immense suffering, made harrowing sacrifices, or both. These leaders’ suffering and sacrifice set them apart from the masses of people who deny, decry, or defy these seemingly unsavory experiences.

Great heroic leaders understand that suffering redeems, augments, defines, humbles, elevates, mobilizes, and enriches us. These enlightened leaders not only refuse to allow suffering and sacrifice to defeat them; they use suffering and sacrifice as assets to be mined for psychological advantages and inspiration. Individuals who successfully plumb the spiritual treasures of suffering and sacrifice have the wisdom and maturity to evolve into society’s most transcendent leaders.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

This article is based on a chapter authored by Scott Allison and Gwendolyn Setterberg, published in ‘Frontiers in Spiritual Leadership’, in 2016. The exact reference for the article is:

Allison, S. T., & Setterberg, G. C. (2016). Suffering and sacrifice: Individual and collective benefits, and implications for leadership. In S. T. Allison, C. T. Kocher, & G. R. Goethals, (Eds), Frontiers in spiritual leadership: Discovering the better angels of our nature. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bibliography

Allison, S. T., & Cecilione, J. L. (2015). Paradoxical truths in heroic leadership: Implications for leadership development and effectiveness. In R. Bolden, M. Witzel, & N. Linacre (Eds.), Leadership paradoxes. London: Routledge.

Allison, S. T., Eylon, D., Beggan, J.K., & Bachelder, J. (2009). The demise of leadership: Positivity and negativity in evaluations of dead leaders. The Leadership Quarterly, 20, 115-129.

Allison, S. T., & Goethals, G. R. (2008). Deifying the dead and downtrodden: Sympathetic figures as inspirational leaders. In C.L. Hoyt, G. R. Goethals, & D. R. Forsyth (Eds.), Leadership at the crossroads: Psychology and leadership. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Allison, S. T., & Goethals, G. R. (2014). “Now he belongs to the ages”: The heroic leadership dynamic and deep narratives of greatness. In Goethals, G. R., Allison, S. T., Kramer, R., & Messick, D. (Eds.), Conceptions of leadership: Enduring ideas and emerging insights. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Campbell, J. (1949). The hero with a thousand faces. New World Library.

Cambpell, J. (1971). Man & Myth: A Conversation with Joseph Campbell. Psychology Today, July 1971.

Diehl, U. (2009). Human suffering as a challenge for the meaning of life. International Journal of Philosophy, Religion, Politics, and the Arts, 4(2).

Frankl, V. (1946). Man’s search for meaning. New York: Beacon Press.

Goethals, G. R. & Allison, S. T. (2012). Making heroes: The construction of courage, competence and virtue. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 46, 183-235. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394281-4.00004-0

Goethals, G. R., & Allison, S. T. (2016). Transforming motives and mentors: The heroic leadership of James MacGregor Burns. Unpublished manuscript, University of Richmond.

Goethals, G. R., Allison, S. T., Kramer, R., & Messick, D. (Eds.) (2014). Conceptions of leadership: Enduring ideas and emerging insights. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gunderman (2002). Is suffering the enemy? The Hastings Center Report, 32, 40-44.

Hall, Langer, & Martin (2010). The role of suffering in human flourishing: Contributions from positive psychology, theology, and philosophy. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 38, 111-121.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Like this:

Like Loading...

By Scott T. Allison and George R. Goethals

By Scott T. Allison and George R. Goethals Hero stories reveal truths and life patterns that our limited minds have trouble understanding using our best logic or rational thought. Transrational phenomena that commonly appear in hero stories include suffering, sacrifice, meaning, love, paradox, mystery, God, and eternity. These phenomena beg to be understood but cannot be fully known using conventional human reason.

Hero stories reveal truths and life patterns that our limited minds have trouble understanding using our best logic or rational thought. Transrational phenomena that commonly appear in hero stories include suffering, sacrifice, meaning, love, paradox, mystery, God, and eternity. These phenomena beg to be understood but cannot be fully known using conventional human reason. unpacking the value of paradoxes unless the contradictions contained within them are illustrated inside a good story. It turns out that hero stories are saturated with paradoxical truths, such as those mentioned by Joseph Campbell in the quote that began Part 1 of this series. Let’s look at each of them:

unpacking the value of paradoxes unless the contradictions contained within them are illustrated inside a good story. It turns out that hero stories are saturated with paradoxical truths, such as those mentioned by Joseph Campbell in the quote that began Part 1 of this series. Let’s look at each of them: transform it in significant ways. The hero, once alone on his journey, becomes united and in communion with the world.

transform it in significant ways. The hero, once alone on his journey, becomes united and in communion with the world.

By Rick Hutchins and Scott T. Allison

By Rick Hutchins and Scott T. Allison

tried to be heroic and failed in the process, but rather that a leader’s heroic imagination failed, thus not allowing her to see the unfolding crisis events as requiring a heroic response.”

tried to be heroic and failed in the process, but rather that a leader’s heroic imagination failed, thus not allowing her to see the unfolding crisis events as requiring a heroic response.” By Scott T. Allison

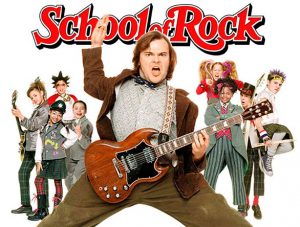

By Scott T. Allison namely, that when we help others, we transform ourselves. In coaching and developing his students’ musical abilities, Finn bonds with these children and defends them with passion when their parents fail to appreciate them. Finn discovers that his life purpose isn’t about making money but about helping others become their best selves.

namely, that when we help others, we transform ourselves. In coaching and developing his students’ musical abilities, Finn bonds with these children and defends them with passion when their parents fail to appreciate them. Finn discovers that his life purpose isn’t about making money but about helping others become their best selves. own transformation as individuals.

own transformation as individuals.