Heroes in the real world are in short supply and usually ambiguous. Consider the three brave men who took down the terrorist on a train in Belgium. I certainly think of them as heroes, and they did likely save many lives, but, in reality, they waited until it was apparent that the terrorist’s gun had jammed before they rushed him. In the movies, such heroes would bring down the villain amidst a hail of bullets.

In the original “Star Wars,” a lone orphaned “farm boy” with only some folk wisdom to guide him single-handedly attacks and eliminates the Death Star, the most lethal weapon ever invented. For forty years now, many of us have waited with much anticipation for the next installment of “Star Wars,” expecting to escape from our own ambiguous and complex world to “a long time ago in a galaxy far far away” in which good and evil are easily distinguished.

According to Dr. Jeffrey Green, a social psychologist at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, Virginia, contemplating acts of heroism inspires us to find meaning and virtue in our own lives. Green invokes the concept of “terror-management,” which refers to the manner in which we deal with the dread of our own mortality. We know we are going to die –but what of our lives will survive our death? Heroes – from real ones like Martin Luther King, Jr. to fictional ones like Luke Skywalker and Harry Potter – achieve an immortality through their heroism.

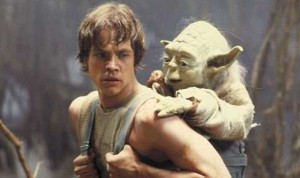

In Green’s view, by identifying with the hero, we perhaps find a bit of immortality for ourselves. For this reason, we identify more with heroes who  are like us in some fundamental way. Luke Skywalker, from his humble beginnings, must find the courage to do the right thing. In this way, Luke is an American hero, self-taught, self-made, accomplishing great things because of his will, his inner belief in himself, and just a bit of manifest destiny. Thus, his triumphs are also ours.

are like us in some fundamental way. Luke Skywalker, from his humble beginnings, must find the courage to do the right thing. In this way, Luke is an American hero, self-taught, self-made, accomplishing great things because of his will, his inner belief in himself, and just a bit of manifest destiny. Thus, his triumphs are also ours.

But “Stars Wars” provides other archetypes – so, if Luke is not the hero we identify with, there are other we can. Hans Solo acts not to right the wrongs of the world, but embodies heroism through loyalty – he won’t leave behind a friend in trouble. Princess Leia, is already a hero at movie’s start – we admire and aspire to her intelligence, courage, and determination. Obi-Wan Kenobi is a hero past who sacrifices himself so Luke can do what’s right. Regardless of who we identify with, through that identification, it brings meaning and comfort to our own struggle to make sense of the world.

According to Green, the true hero sees his or his archenemy as redeemable. This is a fundamentally Christian notion, that even the worst of us can repent and find salvation. The true hero recognizes this and offers this change to the enemy. In “Star Wars,” this Christian notion of forgiveness emerges many times over, including in the final scene of Episode 6, in which Luke’s faith in the goodness of Darth Vader allows Darth Vader himself to conquer both the evil in himself and the evil that controls him. At first, this ending may make us uncomfortable – for years, “Darth Vader” was a synonym for evil. But we also see the complexity of our own lives reflected in the epic struggle of hero and villain, leaving us uplifted by this concept of redemption, so central to our belief system

Thus, deliberately, George Lucas has created an enduring epic myth that appeals to some of our most fundamental beliefs, which spares us – at least for two hours at a time – of the buzzing confusion and ambiguity that is our normal lives.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – –

I like how you tied in the idea of the audience being able to relate to Darth Vader’s internal struggle of being raised to be a hero, but turning to the dark side and ultimately becoming a villain.