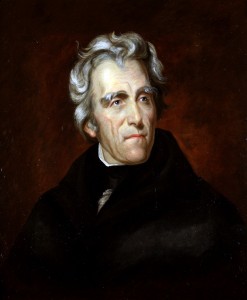

On the surface the 7th President of the United States seems ready made for the mantle of hero. He was born into poverty from Irish immigrant parents in 1767, fought briefly in the American Revolution, studied law and became the prosecuting attorney for western North Carolina, elected to the House of Representatives in 1796, and later the Senate the very next year in 1797. He even served in the state supreme court.

He rose to fame during the War of 1812 when he soundly defeated the British at the Battle of New Orleans using a remarkably egalitarian force of slaves, Haitians, Choctaw, French pirates, Canary Islanders, and frontiersmen. The press declared him a hero and dubbed him “Old Hickory”. He went on to serve as Governor of the newly acquired Territory of Florida. He ran for President in 1824, winning the popular vote but losing the Electoral College. He ran again in 1828 and won and 4 years later won reelection. Andrew Jackson seemed to live a life that, had it been the product of some work of fiction, would seem almost too much to believe. Certainly a hero.

There was another side to Andrew Jackson. He was a man who engaged in duels, killing Charles Dickinson in 1806. During in the First Seminole War he inflicted harsh discipline on his troops, including executions for mutiny. The necessity of some were questioned. Later he would capture two British subjects, Robert Ambrister and Alexander Arbuthnot, and believing them to be agents sent to supply the Seminoles Jackson had them tried and executed. The questionable aspects of the Arbuthnot-Ambrister Incident, which included the invasion of Spanish Territory, would see Jackson investigated by Congress. While Congress would find “fault” with Jackson’s handling of the trial and execution, they would not take any action against Jackson.

And as President Jackson would oversee one of the more shameful moments in American history. In 1830 he signed the Indian Removal Act which called for the forcible removal of Native Americans from their lands. The Cherokee Nation would actually take their fight to the Federal Court in an attempt keep their lands and in Worcester v Georgia The Supreme Court ruled against the relocation. Of the ruling Jackson would reputedly say “John Marshall (the chief justice at the time) has made his decision; now let him enforce it!”. There’s been dispute on whether Jackson in fact uttered those words, but unfortunately they did seem to sum up his attitude. While the Cherokee would not be removed till the Van Buren Administration, the Choctaw, Seminoles, and Creek would see removal under Jackson’s watch.

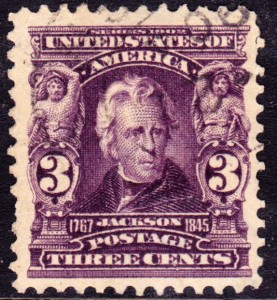

But none of this seems to have affected Jackson’s popularity, which only increased.  After his death his image would appear on no less than 13 postage stamps, have numerous memorials, counties, and cities named after him, his image is on the $20 bill and has been on numerous other denominations over the years. In a 2009 C-SPAN Survey of Presidential Leadership, historians placed him at 13th.

After his death his image would appear on no less than 13 postage stamps, have numerous memorials, counties, and cities named after him, his image is on the $20 bill and has been on numerous other denominations over the years. In a 2009 C-SPAN Survey of Presidential Leadership, historians placed him at 13th.

So was Andrew Jackson a hero for his leadership during his Presidency? A villain for his actions? Both? Neither? This is why the notion of what is a “hero” is so nebulous. Public and historic consensus focused on his actions in the War of 1812, or his handling of the Nullification Crisis, or simply his stellar political career. The darker aspects of his persona are ignored or excused. Jackson certainly wouldn’t be a hero to Native Americans, or the British, or the Spanish. To this day we face these questions when declaring heroes. Do the person’s admirable qualities outweigh the frailty of the human condition? Who decides?

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

The author, Jesse Schultz, routinely has a few $20 bills in his back pocket which he happily sits on.

I think you ask good questions, but I’m not sure this guy is a good example. I don’t see anything in the first two paragraphs that support the statement, “Certainly a hero.” He had political success and success leading on the battlefield. Neither of those require admirable qualities.

Maybe there’s more to his designation as hero, but as presented here, I don’t think there’s much of a contrast.

Nice essay. I like the comment about Jackson being too unbelievable to be a fictional character. I’ve thought the same thing about a few historical figures, especially the Founding Fathers.

I guess Jackson is a textbook example of the “Feet-of-Clay” Syndrome. Heroes, like anyone else, are neither perfect nor consistent. In fact, hero and villain can co-exist in one body. Which does make for interesting fictional characters, but can be problematic in real life.

Excellent and informative. A long time ago I came across a biography of Jackson and read of his loving wife, who died tragically before his inauguration. If that man he killed in a duel was besmirching her honor, he’s a hero to me.

While it is true that heroism, villainy – as well as normal, and weirdness, coolness, uncoolnes – can all vary in perception from individual to individual – it must be understood that the true success of a hero isn’t based on popularity.

Just like I’ve theorized that it’s more heroic to be hated for doing something good, than it is to be loved for doing something bad.

U.S. Presidents are rarely judged on how heroic they were in their executive decisions they made as President. They’re often judged on how “popular” they were. BUT, admittedly this logic can change because even a President like Harry Truman polled at around 23% toward the end of his Presidency, which he left office in 1953. And now he’s remembered as a popular President, because of something he’d done in 1945, dropping the bomb on Japan, thus effectively ending the War. But the heroism people find in something so villainous was based more on a consequential or utilitarian perspective.

When judging the philosophy of heroism, one must determine from which system of ethics they are determining it from. From a Deontological perspective, one judges the merit or demerit of an action based on the action itself. But a Consequentialist perspective bases the merit or demerit not on the act but on the consequence. Utilitarians aren’t against the idea of killing a million innocent people to save a billion innocent people, as they’re more focused on helping the greater number of people.

As a War Veteran, Andrew Jackson had served his country. However, I’ve never been particularly fond of him as a President due to his position on slavery.

Mr. Schultz, thank you for this reasonable essay. Yes, he was a hero because he’s the only American citizen to have an historical age named for him. You are correct though as the legend he became is indeed too good to be true. Almost everything accepted today as proven history should have an asterik/explanation since it was from Public Relations and political propaganda from those times. No, Emma,

Charles Dickinson didn’t besmirch Rachael, they SAID it was over a horserace but the story perpetuated within opposing families say he killed him because he WANTED to. They also said he padded his coat with newspapers, and that’s just the start of it. The real story of Jackson has been lying around for 200 years and no one will publish it because he yet remains powerful and people are scared of him. I’m a Democrat and I’m scared of him too.

I don’t view dueling as showing any personal fault on Jackson’s part. It was an accepted practice of the time and involved two consenting parties. Calling that unheroic would be like a future age criticizing one of our heroes because they used small claims court to resolve disputes, or because they wrote heated editorials against political opponents. These are acceptable practices in our culture.

Likewise, execution is a normal punishment for mutiny or spying, though it sounds like there’s a lot more to the Arbuthnot-Ambrister Incident that I should learn about before I give comment on that.

It’s really Jackson’s behavior as president – disregarding the Supreme Court and authorizing one of our nation’s worst crimes – and his generally reckless, selfish attitude that make hims a villain. He was frankly a dangerous person to have in power.

As an aside to Matt, Jackson’s victory at New Orleans really was stunning – he must have been an incredibly effective leader to unite the various forces that he did, as well as a great strategist to beat such an overwhelming force. I think genius is often a trait that’s deemed heroic, particularly when it leads to victory and saves a threatened city.

(Fun story: According to local New Orleans legend Jackson was then immediately jailed because he (wisely) wanted to put the city on curfew and forestall partying to make sure the British wouldn’t try a second landing. In the morning, the night of drinking safely over, he was released and paraded as a hero.)