By Scott T. Allison and George R. Goethals

By Scott T. Allison and George R. Goethals

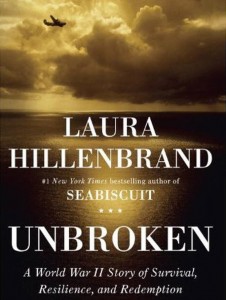

Human warfare brings out the worst in people. Prisoners of war, especially, can be at the receiving end of the most unimaginable brutality. During World War II, Second Lieutenant Louis Zamperini underwent horrific suffering after he survived a plane crash and was sent to several of the most brutal Japanese prison camps. Zamperini’s story is told in bold, vivid detail in Laura Hillenbrand’s book Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience, and Redemption, which was named Time Magazine’s best book of the year in 2010.

Zamperini’s heroic odyssey began with a few successful missions as a bombardier in the Pacific theater in 1942 and 1943. In the spring of 1943, while on a routine mission searching for a lost plane, his own aircraft experienced mechanical trouble and plunged into the ocean about 850 miles west of Hawaii. He and two other men drifted for 46 days on a raft, heading west into Japanese-held waters. They suffered from thirst, starvation, violent storms, intense sunburn, menacing sharks, and strafing from a Japanese plane. After floating 33 days, one of the three men died from starvation.

As much as Zamperini suffered on the raft, he would later recall that it was far preferable to what awaited him after the Japanese captured him on the 47th day near the Marshall Islands. Already in an emaciated state from weeks on the raft, Zamperini was tortured and starved before being transferred to the notorious Ofuna Prisoner of War Camp, which was known for its egregious violations of the terms of the Geneva Convention.  At the Ofuna camp, Zamperini performed slave labor under the watchful eye of Imperial Japanese Army Sergeant Mutsuhiro Watanabe, perhaps the cruelest of all camp guards of World War II.

At the Ofuna camp, Zamperini performed slave labor under the watchful eye of Imperial Japanese Army Sergeant Mutsuhiro Watanabe, perhaps the cruelest of all camp guards of World War II.

The level of hostility directed toward the prisoners by Watanabe was staggering. He especially targeted Zamperini. Watanabe was prone to violent outbursts during which he beat the prisoners daily, starved them, made them perform humiliating acts, refused to treat their illnesses, and exposed them to bitter cold. Watanabe’s level of barbarism was so great that after the war he was classified as a Class-A war criminal. The punishment heaped on Zamperini’s mind and body at the hands of Watanabe was extraordinary.

In one striking example of Watanabe’s sadism, Zamperini was once ordered to hold an extremely heavy wooden beam above his head. He could barely raise it. Watanabe told a guard to strike Zamperini in the face with a gun if he dropped the beam. No one expected Zamperini, in his weakened state, to hold it aloft for more than a few minutes. Watanabe waited for Zamperini’s quick and inevitable failure. Minutes ticked by. Then a half hour. Zamperini recalls the intense pain but also the fierce resolve not to let Watanabe defeat him. After 37 minutes elapsed, Watanabe grew so frustrated waiting that he charged Zamperini and slammed his fist into the prisoner’s stomach, sending them both toppling to the ground. Zamperini’s bold act of strength and defiance gave great inspiration to the throngs of POWs who witnessed the event.

But these moments of triumph were few and far between. By August of 1945, Zamperini was near death, suffering from starvation, exhaustion, dysentery, and beriberi. The dropping of the atomic bombs and Japan’s surrender soon thereafter saved Zamperini and other prisoners, all of them walking skeletons, who somehow managed to cling to life.

Because Zamperini was presumed dead, the reunion with his family was especially poignant. He slowly regained his physical strength, but he suffered from severe post-traumatic stress disorder. Each night in his dreams, Zamperini was haunted by images of Watanabe beating him. Zamperini was agitated, depressed, and unemployed. To soothe his pain, he turned to alcohol and was consumed by revengeful thoughts of returning to Japan to murder Watanabe, the man who ruined his life.

Because Zamperini was presumed dead, the reunion with his family was especially poignant. He slowly regained his physical strength, but he suffered from severe post-traumatic stress disorder. Each night in his dreams, Zamperini was haunted by images of Watanabe beating him. Zamperini was agitated, depressed, and unemployed. To soothe his pain, he turned to alcohol and was consumed by revengeful thoughts of returning to Japan to murder Watanabe, the man who ruined his life.

During this emotionally tumultuous period, Zamperini fell in love with a young woman named Cynthia Applewhite, and they married in 1946. Cynthia was aghast at the level of Zamperini’s emotional pain. One day in 1948 she convinced him to attend a speech given by a young Reverend named Billy Graham. Zamperini was transfixed by Graham’s message of forgiveness. He made a life-changing decision to turn his life over to God and to forgive his Japanese captors, even Watanabe. Zamperini traveled to Japan in 1950 to communicate his forgiveness to his former prison guards, now in prison. The trip went well, but unfortunately Watanabe was nowhere to be found. The cruelest of prison guards in all of World War II had somehow evaded capture.

Zamperini’s religious conversion helped him overcome his emotional scars and lead a happy, productive life. After enduring a plane crash, weeks without food and water on a raft, and appalling treatment at illegal prison camps, Zamperini found a way to survive and even thrive afterward. His military service to his country, by itself, made him a great hero. His remarkable resilience as a POW has made him an inspiration to millions. Today, at the age of 95, he still draws big crowds as a motivational speaker. In Laura Hillenbrand’s words, Louis Zamperini is indeed a man unbroken in mind, in body, and in spirit.