By Scott T. Allison and George R. Goethals

By Scott T. Allison and George R. Goethals

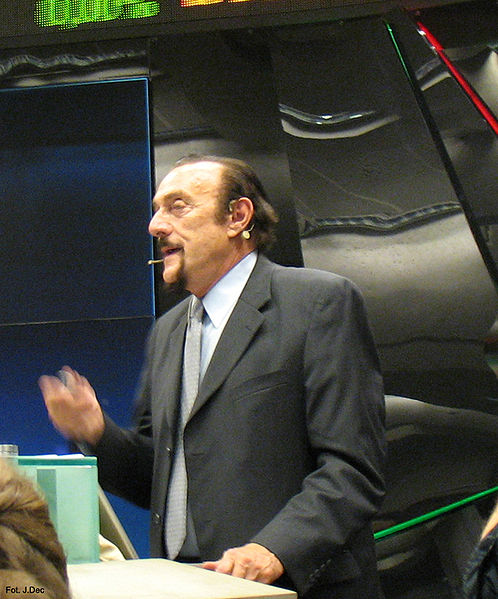

For a variety of reasons, psychologists have been slow to turn their attention to studying the phenomenon of heroism. One reason is that unspeakable acts of evil, such as the Nazi holocaust during World War II, are more likely to grab our attention. Moreover, beginning with Freud, psychology has had a history of focusing on deviant behavior in lieu of positive behavior. But one psychologist, Phil Zimbardo, is devoting his career to showing how an understanding of evil can reveal the human potential for great heroic acts.

In 1971, while on the faculty at Stanford University, Zimbardo and his colleagues (Craig Haney & Curtis Banks) conducted a study of prison life that forever changed our understanding of the dynamics of malevolent behavior. Zimbardo placed an ad in the local newspaper asking for volunteers to participate in a simulated prison study. Seventy-five people volunteered, and Zimbardo chose the 24 most stable and mature of these people to participate. Half of these 24 were randomly selected to play the role of prisoner, and the other half were randomly assigned to play the role of guard. The prison simulation was designed to last 2 weeks, with each person receiving $15 per day for participating. Zimbardo himself assumed the role of prison warden.

Despite the fact that the guards knew that the prisoners had committed no actual crimes, the guards' interactions with the prisoners were hostile and dehumanizing.  By the second day of the study, some of the prisoners showed signs of emotional trauma. By day 6, Zimbardo had to terminate the study out of fear that the prisoners would be harmed physically or suffer permanent emotional damage. Interviewed after the study, many of the guards showed remorse, admitting they had been caught up in the situation. "I really thought I was incapable of this kind of behavior," said one of the more hostile guards.

By the second day of the study, some of the prisoners showed signs of emotional trauma. By day 6, Zimbardo had to terminate the study out of fear that the prisoners would be harmed physically or suffer permanent emotional damage. Interviewed after the study, many of the guards showed remorse, admitting they had been caught up in the situation. "I really thought I was incapable of this kind of behavior," said one of the more hostile guards.

The Stanford prison study vividly shows how evil is often borne out of bad situations, not bad people. Zimbardo points out that when people behave cruelly, explanations often focus on the individual "bad apples" among us. Zimbardo has coined the term The Lucifer Effect to describe evil as originating more from "bad barrels" (the situation) and "bad barrel-makers" (the system). The guards in his study weren't bad people at all. They were responding to the power they felt in their role as guards. Having power over others is the key to understanding evil. According to Zimbardo, "giving people power without oversight is a prescription for abuse." He points to the Abu Ghraib prison scandal and the Jim Jones Peoples Temple disaster as examples of unchecked power causing evil.

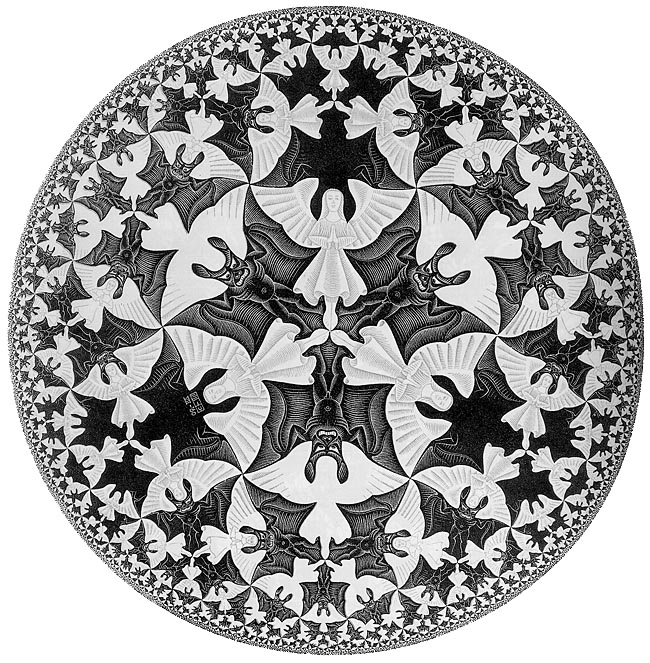

Zimbardo is quick to point out that "the Lucifer Effect focuses on what people can become, not what they are." He adds: "The Lucifer Effect is a celebration of the mind's infinite capacity to make any of us kind or cruel, caring or indifferent, creative or destructive, villains or heroes." He uses a famous M. C. Escher drawing to illustrate his point.  When one looks at the drawing, it appears to be full of demons; if one looks again, it appears to be full of angels. And this is Zimbardo's point. People have the potential for great good or great evil, depending on the situational forces acting upon them.

When one looks at the drawing, it appears to be full of demons; if one looks again, it appears to be full of angels. And this is Zimbardo's point. People have the potential for great good or great evil, depending on the situational forces acting upon them.

Here is the good news: According to Zimbardo, heroism is the antidote to evil. He says, "By promoting the heroic imagination, especially in our kids through our educational system, we want kids to think, €˜I'm a hero in waiting, and I'm waiting for the right situation to come along when I can act heroically.'" Zimbardo's Heroic Imagination Project occupies much of his time now. "My whole life focus is going from understanding evil to understanding heroes," he says.

Zimbardo believes that most of us have an unrealistic view of heroes. "Our kids' heroes are the wrong models for them, because they have supernatural talent. We want kids to recognize that most heroes are everyday people." As a social psychologist, Zimbardo is aware of the power of the situation, as evidenced in his famous Stanford prison study. "Situations have the power to inflame the heroic imagination," he says. "We have to teach kids that to be a hero, you have to learn to be a deviant. You have to do two things: You have to act when others are passive. And you have to give up egocentrism for sociocentrism."

You can see Phil Zimbardo when he co-hosts the Dr. Phil Show on Monday, October 25th. Below is the trailer for his movie Quiet Rage, a documentary on the Stanford prison study.

I wonder about the prison experiment if the “guards” were being influenced by expectations with their abuses. Many movies portray prison guards as being harsh and abusive and I wonder if the participants were subconsciously mimicking what they had seen. That they were expected to act that way.

"By promoting the heroic imagination, especially in our kids through our educational system, we want kids to think, €˜I'm a hero in waiting, and I'm waiting for the right situation to come along when I can act heroically.'"

This is the aspect I’m working with Phil on. He’s given me lots of input on my program, The Hero Construction Company. I’m excited to see what The Heroic Imagination Project produces over the coming years.

Matt, thank you for commenting on this blog post about Phil Zimbardo. I am a big fan of your hero construction company — you do great work! For those interested, please check out Matt’s website: http://www.theheroconstructioncompany.com/main/Home.html

The Hero Construction Company site looks very interesting indeed. “The opposite of a hero is not a villain, it’s a bystander.” Nice. Reminds me of an apocryphal quote from Edmund Burke: “All that is necessary for the triumph of evil is that good men do nothing.”

As for the study, I have to agree with Lupine that there could be confounding factors at work here. If 24 out of 75 were selected for their stability and maturity, what criteria were used for that selection? This is a small sample size and doesn’t seem to be rigorously controlled; it’s possible that, consciously or unconsciously, the participants were chosen to predetermine the results.

Thanks for your comments, Lupine and RJ. In Zimbardo’s prison study, participants were randomly assigned to the role of prisoner or guard, and random assignment usually assures that there are no psychological differences between the two groups.

Another important finding from the study is that the guards’ worst behavior occurred when they believed they were not being observed by the warden (Zimbardo). This suggests that their hostility toward the prisoners was not an act; it was genuine.

The hostility could very have been genuine, my thought is that with no real logical reason to brutalize the “prisoners” (IE they weren’t really criminals)what would be the trigger? With numerous movies and TV shows depicting prison guards treating prisoners in a brutal fashion, I wonder if the “guards” in the study playing the part of guards simply behaving in a manner they’ve seen in entertainment. That they were hiding this from the “Warden” is interesting. In some plots of this type the part of the Warden is at times either a sympathetic character or wishes to maintain an air of plausible deniablity.

Were the results of this study ever compared to actual prison records? It would be very telling to see if the study corresponded with actual prison behavior.

In any event this was a fascinating study.

Lupine, you raise good points, and I’m hoping that someone from Zimbardo’s research team sees this and responds.

The guards brutalized the prisoners because they “internalized” the role of guard, along with all the beliefs, expectations, and behaviors that correspond to their knowledge of that role. You may be right that they obtained those beliefs and behaviors about guards from the culture in which they lived. And that may be the point — we find ourselves in situations that trigger role-based behaviors and mindlessly follow the script that we’ve learned.

I think it’s up to society to change the norms associated with these malevolent scripts. It turns out that correctional facilities have made great strides in this direction since 1971. For example, guards are no longer called guards; they are called correctional officers, which implies a whole different set of (more positive) behaviors.

It’s also incumbent on each of us, as individuals, not to show blind sensitivity to situational cues that lead us to behave badly. And to show heightened sensitivity to cues that can bring out the hero in us.

Scott, thanks for the plug.

I’ll email this article to Phil to see if he can address the questions Lupine has asked.

I do know the 24 had to complete some sort of personality profile. Phil wanted “good boys” for the experiment.

Reply to RJD and Lupine

We all have conceptions of what a Prison is and what it means to be a guard or prisoner–from movies, novels, and media accounts. Those views may differ in different cultures but in the US, it is all about Power and its abuse. Guards must demonstrate to prisoners that they have virtually total power over them, and the prisoners are powerless to change their situation for the better, other than by blindly obeying all the coercive rules of the prison. So our student-participants likely brought such views into the experiment to influence their role-relevant behavior.

But consider that the year was 1971, most of our participants were “hippies,” anti-war activists, and in general challenged authority. Not one expressed a preference to be a guard rather than a prisoner prior to the start of the experiment. There is no evidence that we had selected as guards those with more sadistic tendencies, since selection to roles was totally random.

Our selection of 24 participants from the 75 who answered our ad was based on each of them being in the “normal range” on each of 7 scales of the Comrey Personality Inventory (from UCLA), and also were judged to be normal, healthy based on their interviews with our staff. The point is simply that on day 1 of the Stanford Prison Exp we had only good apples in our bad barrel. By day 5

many of them had been corrupted by the power of the situation– in ways that I describe in great detail in the first 10 chapters of my book, THE LUCIFER EFFECT, UNDERSTANDING HOW GOOD PEOPLE TURN EVIL (RANDOM HOUSE, 2008).

Thank you for clarifying those details, Professor Zimbardo. This is very interesting in light of the personality test that was administered and the anti-establishment nature of the participants. The idea of internalized scripts from popular culture being triggered in situations like this is fascinating. Most people do live according to behavioral scripts, certainly, but such drastic changes in behavior in so short a time definitely merits further attention.

This discussion has just dredged up an ancient memory of a PBS show I saw back in the 70s starring William Shatner. The title was something along the lines of The 10th Level, I think. It concerned a study to determine the degree one person was willing to torture another, or something along those lines. I’ll have to research it.

RJ, I believe you’re referring to William Shatner’s portrayal of Stanley Milgram, who conducted a number of remarkable studies in the 1960s showing that people will blindly obey an authority’s instruction to apply painful electric shocks to others. I’d love to see that PBS show again. I can still remember the camera panning in on Shatner’s face as he is stunned to witness a painful reality of human nature: When placed in the wrong situation, humans are capable of unspeakable cruelty toward each other.

That’s exactly it, Scotty, and I was even right about the name– except it’s Tenth Level, not 10th Level. There’s an IMDB page here: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0075320/ and it seems to be available for viewing on YouTube, but not available on DVD.

Phil went to grade school with Stanley Milgram oddly enough!

“You have to act when others are passive. And you have to give up egocentrism for sociocentrism."

This is such an interesting definition of heroism, someone should try and empirically test/prove this.

I’ve study the prison experiment in Dr. Forsyth’s Leadership class. Personally I don’t like Phil Zimbardo. He puts the “prisoner” in really dangerous situation. One guard said in the interview that he tried to be hostile and dehumanizing like a role he watched in the film. That actually make the experiment worse. All other guards are influenced by his leadership and although other guards didn’t agree, they keep silent. Thus, I don’t think it’s a successful experiment and Phil Zimbardo should be blamed for his careless selection of volunteer.