The ingredients of heroism are well known to storytellers. A hero embarks on a journey of some kind that begins when he or she is cast into a dangerous, unfamiliar world. The hero is charged with accomplishing a daunting task and receives assistance from unlikely sources. There are frightening obstacles along the way and villainous characters to overcome. After many trials and much suffering, the hero prevails and then bestows a gift to society.

Often overlooked in this journey is the key to the hero’s success, namely, the hero’s acquisition of an important quality that he or she lacks. All heroes start out “incomplete” in some sense. They lack some essential inner quality that they must develop to succeed. This quality can be self-confidence, humility, courage, compassion, faith, resilience, or some fundamental truth about themselves and the world.

The question I have for you, the reader, is: What inner quality are you missing that is holding you back from becoming the hero of your own life story? Another way to put it: What attributes are you missing that you need for success?

If you’re like millions of people, you aren’t sure what you’re missing. Circumstances may not yet have revealed your missing quality. Or people have yet to enter your life who can guide you. If that’s the case, be patient. Buddhists have a saying: “When the student is ready, the teacher will appear.”

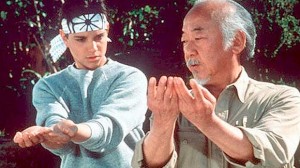

Who are the teachers in your life? Let’s look at two examples of how heroes in the movies have received help from others to receive their missing qualities.

Who are the teachers in your life? Let’s look at two examples of how heroes in the movies have received help from others to receive their missing qualities.

The Wizard of Oz. In the classic 1939 movie, The Wizard of Oz, Dorothy is sent by a tornado to the strange Land of Oz. Her quest is to find her way home, and she receives help from three unlikely sources—a scarecrow, a tin man, and a lion. She is mentored by a friendly witch named Glinda and, later, by a mysterious wizard. Along the way she overcomes an evil witch, flying monkeys, and apple-throwing trees.

Dorothy’s missing quality is an understanding of “home”. Her new friends teach her that she has always possessed the power to get home. She discovers that home means more than just your house or apartment. It’s wherever the people you love—and who love you—are found.

Gravity. Nominated for Best Picture in 2013, Gravity stars Sandra Bullock as Dr. Ryan Stone, a scientist stranded in space after her space capsule is damaged. Dr. Stone is terrified and appears to lack the confidence and inner resources to survive her dire situation.

Veteran astronaut Matt Kowalski, played by George Clooney, is there to mentor her and instill her with confidence. Dr. Stone summons the courage and resourcefulness to cheat death and return to earth safely.

Movie heroes are not the only ones who benefit from good mentor figures. Rocker Gene Simmons credits his mother for teaching him prudence and self-control. Actor Jennifer Lawrence has thanked her father for helping her learn how to deal with adversity. Barack Obama has said that his grandmother, Madelyn Dunham, taught him the importance of sacrifice: “She’s the one who put off buying a new car or a new dress for herself so that I could have a better life.”

In every good hero story, the hero discovers that he or she is missing something and receives help from others to acquire what’s missing. Every human life is a hero-like journey, making it imperative that each one of us identifies our missing quality.

Here are four steps you can take—not necessarily in this order:

1. Make an inventory of your strengths and weaknesses as a person.

1. Make an inventory of your strengths and weaknesses as a person.

2. Develop a list of your life goals.

3. Assess what’s missing to achieve your goals. List the strengths you lack and the weaknesses that need removal.

4. Find mentor figures to help you.

Some people do Step 4 first. A good mentor can help you identify your strengths and pinpoint what qualities are needed to fulfill your goals. Good mentors should be brutally honest about what you’re missing and how to acquire the qualities you lack.

Many of us fail, and fail badly, before we are willing to seek the help of a mentor figure. Learning from our failures and getting help from mentors is a sign of healthy human development.

Identifying missing qualities and acquiring them is essential for heroes to succeed with their missions. The discovery (or recovery) of these attributes is the basis for the personal transformation that the hero undergoes during the journey. The most satisfying heroes we encounter in storytelling and in real life are heroes who experience this transformative discovery of their missing quality.

One final caveat: Beware the dark mentor. As movies such as Whiplash and Fifty Shades of Grey show us, there are false mentors out there who will send you in the wrong direction. Choose your teachers carefully.

References

Allison, S. T., & Goethals, G. R. (2011). Heroes: What they do and why we need them. New York: Oxford University Press.

Allison, S. T., & Goethals, G. R. (2013). Heroic leadership: An influence taxonomy of 100 exceptional individuals. New York: Routledge.

Campbell, J. (1949). The hero with a thousand faces. New York: New World Library.

Franco, Z. E., Blau, K., & Zimbardo, P. G. (2011). Heroism: A conceptual analysis and differentiation between heroic action and altruism. Review of General Psychology, 15, 99-113.

Goethals, G. R., & Allison, S. T. (2012). Making heroes: The construction of courage, competence, and virtue. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. San Diego: Elsevier.

Smith, G., & Allison, S. T. (2014). Reel heroes, Volume 1. Agile Writer Press.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – –