By Steven Gu

[Editor’s note: What follows is a story written in early March as the author drove home to California after the University of Richmond closed its campus in response to the outbreak of coronavirus.]

___________________________________________

“STATE LAW Move Over Unless Passing.”

This law has been on my mind lately.

Driving from Virginia to California, one starts on the Interstate 64, then you get on Highway 70. After that I-80 goes all the way to San Francisco. The weather along the way is unpredictable; It can be foggy in the Rockies, pouring in Illinois, cloudy across Kansas, snowing throughout Colorado, and sunny over Utah. Eventually, five days and three thousand miles later, the Atlantic turns into the Pacific and Waffle House into IN-N-OUT Burgers. However, this time, I, a college freshman, who has just been told to go home by my university due to the Covid-19 pandemic, and my puppy Atticus are driving slow to drive far.

Truck drivers and their giant semi-trucks are a common sight of the United States Interstate system. These truck drivers commonly referred to as truckers, make up the lifeline of this country. They haul everything from much-needed toilet paper to behemoth factory robots. Some of the trucks are the extended cab, covered in lights and stickers while others are just plain, white, and maybe displaying a Walmart logo or no logo at all.

Often and almost always, we pass truckers. They are slow, heavy, and potentially really dangerous. This time, however, I was passed by the truckers, constantly needing to “move over.” Trust me, it was not by choice. This is a pure electric, cross country journey using not a single drop of fossil fuel. As much as I would like to say driving an electric car is just like a gasoline car, that is just simply not true. You have to go much slower if you want to travel far.

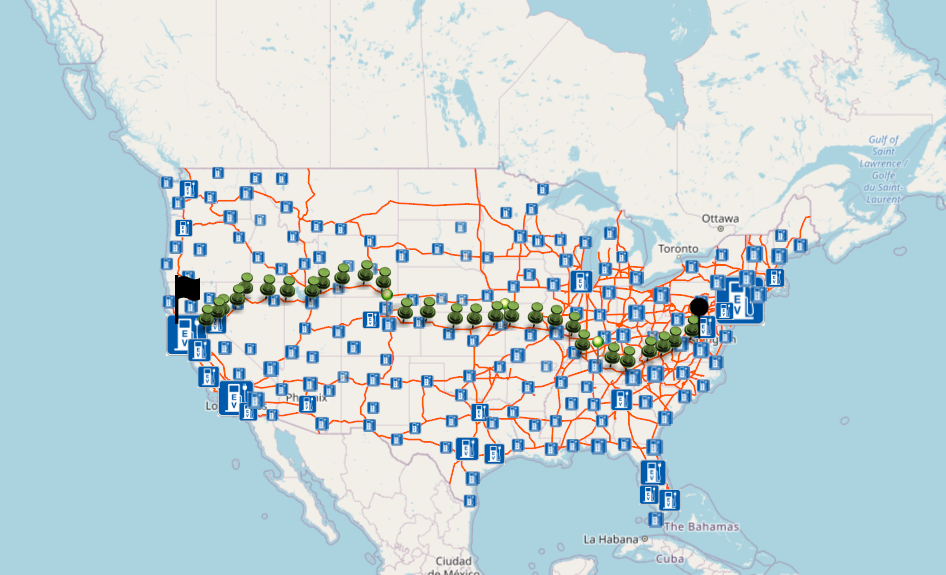

Go slow to travel far. The state of the battery is such that fifty-five miles, the original speed limit of the interstate system is the most efficient speed. It has to do with complex battery chemistry as well as excessive wind resistance. The same is true for cars powered by gasoline. There was even a time period in the 1970s when President Nixon forced all freeway in the United State to abide by the fifty-five miles per hour speed limit. The only difference is gas stations are now all over the country and fossil fuel seems to be endless. On the other hand, charging stations are still fairly hard to come by and much planning is needed.

Today, driving at 55 miles per hour is deemed to be dangerously slow. You can almost feel the angry stares from the other motorists who have to put in all the extra work to signal, turn their steering wheel, and pass this slow-moving vehicle. But it has not always been this way.

More than a century ago, in the fall of 1888, 39-year-old Bertha Benz embarked on a history-making, long-distance “road trip” across Germany in a hand-built Model 3. Without fuel stations or any directions, she and her two sons were driving towards the future, proving what is possible, traveling slow to go far.

Bertha Benz-The Journey That Changed Everything, Video by Mercedes-Benz

Their speed, a laughable ten miles per hour, still left people stunned on the side of the road. Speed is not merely just a number. It is not absolute but relative. What we see as slow was once fast. In the future, what we see as fast will become slow.

So why do we go fast? Driving is the single most deadly activity we do daily. Yet, we continue to go faster and faster. Not to mention it is way less efficient when you drive fast. It maybe has to do with the concept of cross country driving. You are heading toward a destination that you can not see. What really do four hundred and thirty miles mean and what is the difference between going 70mph and 74mph. The only thing you see is what is around you, the other cars. Your speed is not the speed you need to get to your destination, but rather what is appropriate for cars near you. Perhaps, we go fast because we can, but also because we need to.

When you slow down, a lot of things start to happen. Yes, other drivers start to pass you. Yes, truckers start to pass you. But more often than not, you start to see more things. On my previous cross country trip, I drove at a modest 85 miles per hour most of the way. Driving at that speed, your full attention is on the road and only the road ahead of you. This time, I feel the freedom to occasionally scan the scenery and look around (while driving safely of course). The mad glance from drivers who just passed me is often some of my favorite moments of the trip. Two separate cars, heading towards two very different destinations, inside each metal box is a tale that lasts a lifetime. For a brief moment in the grand scale of history, the two of you connect. Then off you go.

Next time, try driving slow when you want to travel far.

Author’s note: This article was inspired by Paul Salopek’s dispatch, “Go Slowly, Work Slowly.”

This is Paul’s first long dispatch after getting off the cargo ship that brought him across the Red Sea. Paul was “unable to read or write, to concentrate…” aboard the boat. In many ways, this is my own story after driving cross-country. When you are driving, regardless of the speed, you can only focus on the road. At the end of the day, you are so tired and have little time or energy to do anything.

Both of us are overdosed on speed. Both of our writing starts with what we observed. For Paul, it is the observation of the Ethiopian truck drivers. For me, it is “slow driving,” paying attention to the road while observing the passing scenery and other drivers. Paul is going slow on purpose. I am going slow because that is the only way to reach my destination. We both discovered something unintended when we travel. For Paul, it is how the boat journey has thrown him off balance. For me, it is the strange beauty of that passing glance. We are slow-moving creatures.