The sun’s glowing rays reflected off the hospital’s tinted windows. In a garden nearby, newly sprouted tulips burst with color, yellow and white, while across the road tree saplings, planted in neat rows, seemed to go on forever. It was a new season, a new era. The Earth has not forgotten its habits. Animals emerge from hibernation. Plants resurface from beneath the soil. And all the world’s colors rise up, vibrant and alive. Against the backdrop of a pandemic, of chaos, of anxiety and pain, Spring creates a cruel contrast.

Bonnie Loomis, my mom, walked out of the building in her turtle neck sweater and long navy pants. The pandemic has not allowed her time to change into her warm-weather wardrobe. She works for the Penn State Health System’s Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, as the Medical Office Supervisor of the Sleep Research and Treatment Center.

The hospital is a central part of the town. Named after the esteemed chocolate maker, Milton Hershey, the hospital is a hub of socialization and community. It employs over 1,000 physicians, 2,000 nurses, and 10,000 staff workers. It is distinguished in its reputation and ability.

“I need to get my sunglasses out of the car before we go on a walk,” Bonnie said. Before we made it out of the parking lot, we were approached by her coworker, Dena Meyers.

“I’m just coming in to get a laptop computer,” Dena said.

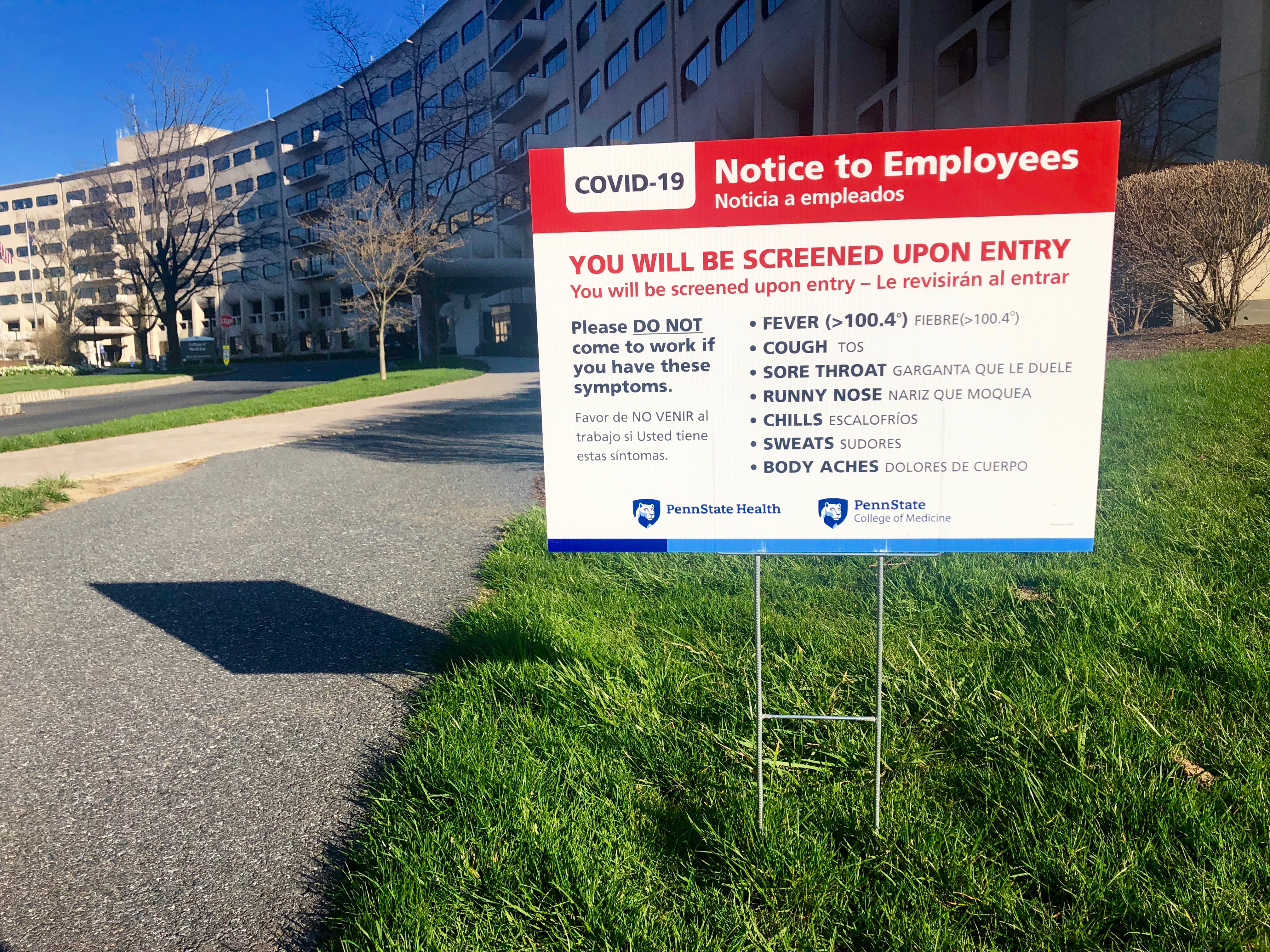

Right now, Dena is arguably one of the most important workers in the hospital. Usually a Sleep Technician, she volunteered to become a COVID-19 Screener, acting as a barrier between the hospital and the rest of the world. Before anyone is permitted to enter, she screens them for symptoms of Coronavirus. Dena works a 12-hour shift, from 6:00 pm to 6:00 am, while wearing a mask, a plastic eye shield, and gloves.

Her tie-dye Crocs and oversized sweatshirt indicated new priorities for her too. Amid a pandemic, the hospital dress code is no longer a concern.

“The doctors, they’re worse than the patients,” said Dena. “They come in with a sore throat and a fever thinking they can work. I have to tell them to fill out this paperwork, so I can notify their supervisors they will not be coming in. It makes me worried for my five-year-old son. I wear a mask and gloves, and I change my clothes before I get into my car. But I’m not going to pick him up after work and then give the virus to him. That’s not fair.”

Dena left for her shift and we continued on our way. We followed the sidewalk leading to the main hospital, past a large sign hastily erected at the entrance. Bright orange letters read NO VISITORS ALLOWED.

“I read a lot of things sent from the hospital, and I feel safe,” my mom said as we passed another COVID-19 warning sign. “Then I go to the grocery store and see people wearing masks and I think, ‘what did I miss?’. My workspace is a bubble of safety. But then I’m reminded of the eminent fear every time I walk outside.”

The Sleep Research Center, like most of the hospital, has transitioned to telehealth. Patients are not permitted to come in for their appointments.

“I feel safe at work,” my mom continued. “If I didn’t feel safe, I would stay home. We get email updates three or four times a day about COVID-19 screening and the safety precautions of patients and staff. If there were patients coming in, I would feel differently. But no patients come in now, so I do feel safe.”

Appointments by phone have left the campus desolate. A few cars in the parking lot were the only indication of activity within the walls of the hospital.

“The biggest change in my job is the unpredictability. Most of the department’s employees are still working, either remotely or in a different position so they can get a paycheck. Only one person from our department is not working because of her fear.”

Bonnie abruptly stopped walking.

“Ironically the only people who have to come in to work and risk their health are the Medical Office Assistants, the lowest paid people in the department. The amount of time it would take to get them all acclimated for working remote and having IT set them up would be almost impossible. And they are coming in with smiles on their faces and no complaints.” She paused and continued, “This happens a lot. Those at the bottom are left doing the grunt work.”

I thought of the grocery clerks bagging groceries. The postal workers walking house to house. The pharmacists distributing prescriptions. And then, Dena.

We stopped across from the main hospital entrance doors. Yellow tulips invited our presence underneath the cloudless sky. Death was close, danger nearby. Inside, brave humans bearing the burdens of an entire world. The least we can do is thank them.