The Philadelphia History Museum is a two-level city history museum, claiming to be “your gateway into Philadelphia’s past!”. It has a daunting task before it: telling the history of the city of Philadelphia. The museum uses its exhibits to proudly show us where the city has been and question where it will go. Though its story was one of Philadelphian pride, the museum did not shy away from acknowledging tensions, such as those between races and citizens and government. The exhibit on preserving historic sites in Philadelphia, “Saved! Preserving Old Philadelphia: 85 Years of The Philadelphia Society for the Preservation of Landmarks,” used unique storytelling and interactive methods to describe the challenges in preserving Philadelphia’s history.

Uncategorized

On Violence, Resistance, and Self-Determination

By Hunter Moyler

As I’ve been working with Untold RVA and Free Egunfemi this summer, two of the aspects of Richmond history I’ve been tasked with finding and recording is that of Black resistance to adverse power structures and self-determination.

“Self-determination,” as you might deduce, refers to a person’s ability to determine their own fate and the steps they take in order to overcome the adversity that may prevent them from doing so. “Resistance” is similar. It denotes the avenues by which marginalized groups challenge the unjust social order of their day. I’ve found that in the era of slavery, which most of my research has centered around, a plethora of the deliberate acts of self-determination and resistance included radical, often violent, subversions of laws, laws created to fence-off African Americans from achieving anything approaching equity with their European contemporaries.

And when I say violent, I mean it. Look no further Angela Barnett, a free Black woman who lived in Richmond in the late eighteenth century, who killed a man who broke into her house under the suspicion that she was harboring an escaped enslaved man. (Sidbury, Ploughsares into Swords, 4) Or, take Martha Morriset, an enslaved woman who, along with others living on Chesterfield County plantation, murdered her so-called “mistress” after she tried to “correct” her and then chopped up her body and tossed the remains in the James. (Sidbury, 220 – 221) And, of course, I’d be tragically remiss not to mention that General Gabriel, as part of his unfructified plan to establish a free Virginia, intended to kill all Whites “except Quakers, Methodists, and French people” (Amateau, Come August, Come Freedom, 220) until Governor Monroe assented to the soldiers’ demands for emancipation for all of the Old Dominion’s Black population.

The actions of these people were certainly bold moves to take their lives into their own hands and subvert their oppressors, and of course these ought to be recorded and remembered. Each time I read about the enslaved retaliating against their captors, I take note of it. But such reading has placed a smorgasbord of food for thought in front of me, and I’m beginning to feel a smidge bloated.

Archiving: A Detective’s Work

By Maryam Tahseen

I remember delving into archiving in my second week of research with no idea as to what I would find. Just like any detective, I decided to understand the background of my case before I investigated further into the details. I started my investigation by going through Collegian articles from 1914 to 1975. As I went through newspaper articles from the Collegian, I started identifying the various themes that existed during different timeframes. I found out that 1950s was a time of immense support for the Confederate cause while 1960s revolved around discussions of integration of the university. As I moved into the 1970s, I realized that it was a decade of changes and activism.

Museum of the Confederacy: I Am Sorry My Dear, but You Are Up for Elimination

by Joshua Kim

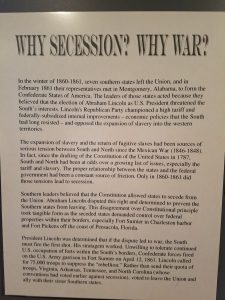

Picture this. You, an innocent, pop-culture savvy, Korean-American student at the University of Richmond, exploring the Museum of the Confederacy. You read the sign in the entrance:

“The leaders of those states acted because they believed that the election of Abraham Lincoln as U.S. President threatened the South’s interests. Lincoln’s Republican Party…opposed the expansion of slavery into the western territories. The expansion of slavery and the return of fugitive slaves had been sources of serious tension between South and North since the Mexican War (1846-1848). …Only in 1860-1861 did those tensions lead to secession.”

Cool. Awesome. Sweet. You feel reassured that the museum will be inclusive of those who were enslaved by white-colonial Americans, aka Africans. So you begin your self-led tour of the museum.

Confederacy. Union. Freedom.

by Cory Schutter

On the tinted glass doors of the museum are three words: Confederacy. Union. Freedom.

These words frame a visit to the Museum of the Confederacy — three complicated, tense, load-bearing words. They frame the Civil War as an idealistic fight for freedom, and I wonder about the truth in this. When we talk about freedom, to whose freedom do we refer?

Maymont’s Unsung Heroes

by Catherine Franceski

As I walked through Maymont’s gates on a balmy summer morning, I imagined that I must have felt exactly as many visitors did around the turn of the 20th century– full of awe and wonder. Today, Maymont encompasses a Gilded Age mansion, a petting zoo, and extensive gardens and grounds. Acquired in 1886 by James and Sallie May Dooley, Maymont, an 100 acre estate on the banks of the James River, was undoubtedly one of the largest properties owned in Richmond. James Dooley was a confederate major in his youth and later became a prominent lawyer and businessman. His wife, Sallie, grew up on a Virginia plantation and later wrote “Dem Good Ole Days,” a collection of short works glorifying the Antebellum period written from the perspective of an enslaved person. The couple, having no heirs, donated Maymont to the city of Richmond after Sallie’s death in 1925.

This Week in the Archive: A Reflection for the Change Conformers, Absurd Plastic Hippies, and System Dissenters

by Dominique Harrington

I’ve read, Jarett Drake’s, “Documenting Dissent in the Contemporary College Archive: Finding our Function within the Liberal Arts”, a few times, as I worked with the University of Richmond’s Race & Racism Project this past fall. I’m more and more convinced as to the inherent liberatory and reconciliatory nature of archives each time I read it. Towards the end of this piece, Drake discussed having an Ida B. Wells quote printed on a t-shirt, “Those who commit murders write the reports…” However, it wasn’t until my third time reading this piece that I was inspired to looked up the context of the quote. It is an excerpt from an anti-lynching speech that Wells gave on February 13, 1893, which was later published in Our Day magazine in May of that same year. Many folks are familiar with the popular phrase, “History is told by those who win.” However, with this quote, Wells offered a slightly different manifestation of this notion. Rather than looking at history through a lens of triumph or defeat, she astutely points out that we must also look at historical figures as those actively perpetuating systems of oppression, whether it be as intentional and explicit as lynching, or whether it is an instance where the Dean of a conservative women’s college submitted a report sharing her appraisal of the untraditional direction she felt that her students were drifting.

The Valentine: An Inclusive Richmond

By Benjamin Pomerantz

A few weeks ago, I visited The Valentine, a museum in the city of Richmond that focuses on telling the story of Richmond’s history. Now, to be clear, there are many ways and many perspectives from which to develop a historical narrative–from the white Confederate point of view, from the enslaved point of view, from the free black point of view, from the immigrant point of view, etc. Based on my experience, I thought that the curators of The Valentine did their best to make the museum’s narrative of Richmond’s history inclusive of all Richmonders. Instead of focusing on the story of a certain population of Richmond, The Valentine includes many perspectives of Richmond in an attempt to portray Richmond as a diverse city with people of many interacting beliefs, customs, and lifestyles. As someone partnering with Untold RVA, it was exciting to see stories of black self-determination and resistance at a Richmond museum, especially because the city tends to memorialize the legacy of the Confederacy as opposed to the lives of enslaved people and free blacks in Richmond.

A Visit to Maymont

By Jennifer Munnings

Maymont, what once was the home of James and Sallie Dooley, is best described as superfluous. As Catherine and I walked through the Japanese and Italian gardens we were struck by the immense beauty of Maymont. There were vibrant flowers all around, and as we explored, the quiet rush of a waterfall played in the background. The Gilded Age mansion was a grand display of wealth, walls were lined with gold, whole rooms were decorated by Tiffany, and there was an ivory vanity made from narwhal instead of elephant tusk.

Signing Off

In this week’s episode of Expanding the Ivory Tower, Victoria shares some final reflections about her research.