by Cole Richard

Cole Richard is a junior from Orlando, Florida double majoring in English and Italian Studies and minoring in Linguistics. This is his first summer working on the Race & Racism project. He is also a resident assistant, DJ at the campus radio station, and student worker at the music library.

In reflecting on the entirety of the oral history process — from interviewing to creating a podcast — I’ve gained a better understanding of how to interview in order to get quality material. Interview material moves through a multitude of contexts. There’s a pretty big difference between the interview itself and the final product, the podcast. Although my podcast was created from the audio collected in an oral history, its shorter length and more polished production result in it having a larger audience. Because of this, material that may have been sufficient for the purposes of the interview and oral history wound up being not as well suited for the podcast.

In reflecting on the entirety of the oral history process — from interviewing to creating a podcast — I’ve gained a better understanding of how to interview in order to get quality material. Interview material moves through a multitude of contexts. There’s a pretty big difference between the interview itself and the final product, the podcast. Although my podcast was created from the audio collected in an oral history, its shorter length and more polished production result in it having a larger audience. Because of this, material that may have been sufficient for the purposes of the interview and oral history wound up being not as well suited for the podcast.

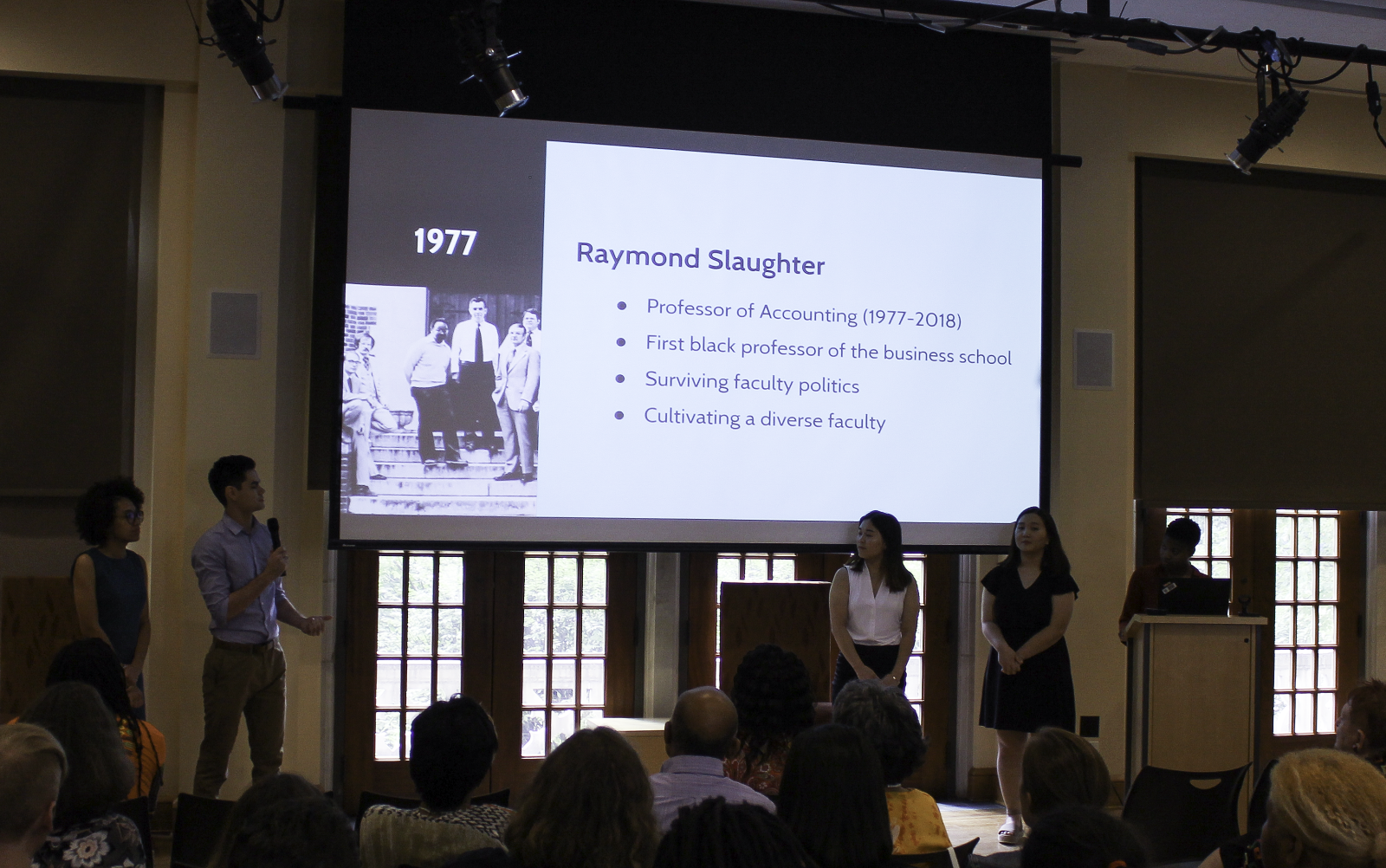

Specifically, I learned the importance of having interview subjects explicitly state critical pieces of information. For instance, during my interview with Professor Raymond Slaughter, he detailed certain policies and practices that I understood to be inherently discriminatory, so I didn’t bother to ask him how they were discriminatory. While this was fine for the purposes of the interview itself — in the context of the full oral history it is easy to understand the bigger picture in what he was telling me — I found myself wishing I had asked that question when I was editing my podcast. Without that soundbite of him explaining it, I had to supplement the explanation with voice over and other clips from the interview to better provide commentary. That’s not to say that I wish I had tailored my interviews to getting “juicy soundbites,” but rather that having a better understanding of the editing process would have resulted in acquiring more useful material.

Further, providing voice over narration for a podcast constructed from an oral history is a delicate process. While writing my script I was constantly self-interrogating, “Is this too much? Am I telling this person’s story for them? Am I appropriating their words for my own narrative?” The Oral History Association defines “Narrator” as “a person being interviewed during an oral history recording.” How then am I, for the sake of brevity and ease of listening, supposed to voice-over (i.e. narrate) another person’s narration of their own life? While I can’t provide a definitive answer to this question, I believe my approach maintained the integrity of the original oral history. I settled on using voice over sparingly to introduce what Professor Slaughter was about to speak on and to provide a description of tenure that was necessary to understanding much of what Slaughter spoke about. I made sure to both open and close the piece with Slaughter’s voice to better convey that the story being told was his own.

Initially this structure of narration resulted in a piece that was more than five minutes over the recommended length. I was preoccupied with ensuring that Slaughter’s words remained intact and wanted the podcast to play like a condensed version of the full oral history. This approach was wrong, and the advice of my mentors to “lean into the specificity” of the subject — the discriminatory impact of tenure and advancement policies — led me to strip away much of the excess material. I had planned on having a section of the podcast dedicated to Slaughter’s service-oriented career (e.g. bringing the Volunteer Income Tax Assistance program to the university), but removed it because it wasn’t essential to the focus of the piece. Although the decision to remove this section from the podcast wasn’t easy, I hope that my final product can in turn lead interested listeners to listening to the oral history in its entirety.

At the start of the summer, I hardly considered the potential difficulty of the podcast creation process. I figured the only challenging part would be conducting the actual interviews; editing and scripting was an afterthought. I had listened to plenty of podcasts before, so I had a sense of how the finished product would have to flow. What I didn’t realize though, was the sheer labor that goes into getting raw material to that state. I don’t mean selecting the specific clips to use (i.e 10% of all material recorded). In truth, before even selecting the clips, I had to identify the narrative that I was trying to share. This was in fact the most difficult part, as I had to be cognizant of the problems inherent with editing another person’s oral history. It is my hope that my podcast, “Something Wrong with the System” remains faithful to Raymond Slaughter’s words while providing an accessible entry to the world of oral histories.