by Sabrina Garcia

Sabrina Garcia is a junior from, Waldwick, New Jersey double majoring in Leadership Studies and English and minoring in Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies (WGSS). This is her first year working on the Race & Racism Project, on Team Archive. Sabrina is in the WILL* Program, works as a writing consultant, and is training to be a PSMA. She hopes to dedicate her career to social justice and believes in the mission of Race & Racism wholeheartedly.

Walking into the West Hospital at the V.C.U. Medical Center, I could not help but wonder how I was going to find the Jefferson Davis Memorial Chapel, as there was no clear signage or indication that this hospital would have such a site. The only information I was able to find online was through a blog post on The Shockoe Examiner written by Selden Richardson. However, once I walked into the building, there was a plaque that stated that the Jefferson Davis Memorial Chapel was located on the 17th floor. Once in the elevator I noticed that there was no indication in the labels of where the monument was and, taking the plaque for truth, I clicked the button for the 17th floor. Upon arriving there is no guidance to where one should head, and after a bit of searching; behind a plain door with a small window, we (Nathan and Gabby, who are also on Team Archive) observed a long hallway leading to a dark room, with a marble archway labeled Jefferson Davis Memorial Chapel.

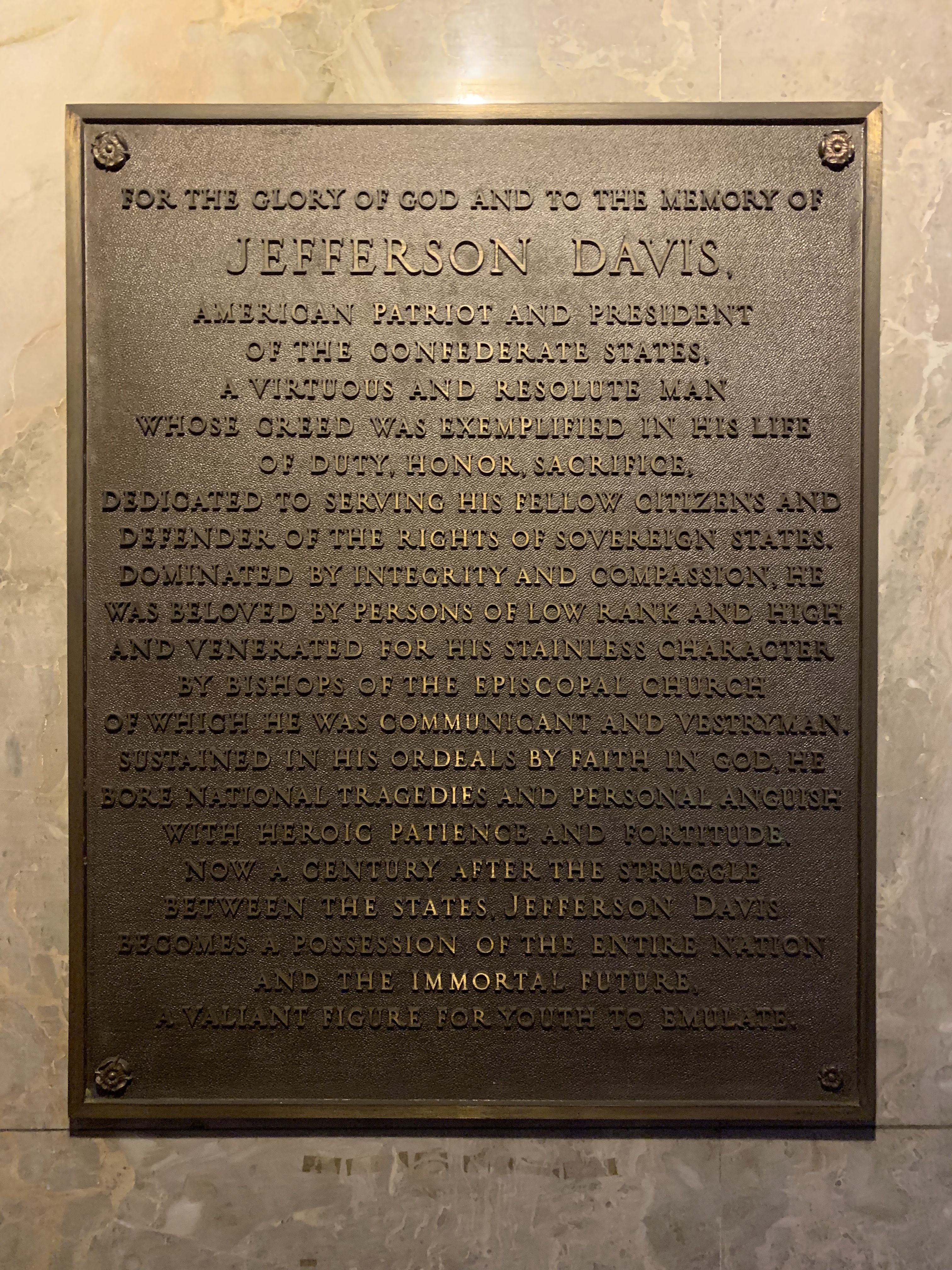

Upon entering the chapel, one cannot help but feel an eerie sense of dread, the opposite intent of what a religious space is meant to offer. The chapel is extremely small, and the lack of lighting or windows, despite being on the highest floor, made the room feel as though it was slowly closing in. As you can see in the second photo, the only light sources come from the door you entered through and the light on the alter. Upon the alter is a Bible, flowers, candles, an ornate cross, and a simple painting of Jesus. There are three plaques in the chapel, two of which celebrate Jefferson Davis, naming him an “American patriot and president of the Confederate States” and a “defender of the southern states.” There is also a plaque dedicated to Kathryn Slaughter Wittichen, who was President of the Daughters of the Confederacy and a key figure in getting the memorial chapel built in 1960.

Upon entering the chapel, one cannot help but feel an eerie sense of dread, the opposite intent of what a religious space is meant to offer. The chapel is extremely small, and the lack of lighting or windows, despite being on the highest floor, made the room feel as though it was slowly closing in. As you can see in the second photo, the only light sources come from the door you entered through and the light on the alter. Upon the alter is a Bible, flowers, candles, an ornate cross, and a simple painting of Jesus. There are three plaques in the chapel, two of which celebrate Jefferson Davis, naming him an “American patriot and president of the Confederate States” and a “defender of the southern states.” There is also a plaque dedicated to Kathryn Slaughter Wittichen, who was President of the Daughters of the Confederacy and a key figure in getting the memorial chapel built in 1960.

After spending about ten minutes or so in the chapel memorial, I felt as though I could no longer be in the space as the curved low ceilings and lack of light began to make me feel extremely uncomfortable. Upon leaving the building, we ran into a worker who accompanied us on the elevator and spoke to us about the chapel, letting us know that “a sweet couple” had had a wedding in the chapel “a while back.” I left the West Hospital feeling confused, disturbed, and uneasy at seeing such a site. As someone from a Northeastern state, I had prior understanding that such Confederate monuments would have been built at the height of Jim Crow, however finally seeing them in person brought forth the understanding of how deep this history runs, and how Confederate ideology continues to live on in spaces such as these.

The purpose of this chapel, upon reflection, is difficult to understand, as Jefferson Davis’ legacy is not representative of peace; he is associated with racist ideals, violence, and war. Chapels are places for worship and hope, and in a hospital setting a chapel becomes a reprieve from sick loved ones. Although the West Hospital currently does not hold patients, when it was in use the chapel was also likely used by families and patients. The hospital is also a part of VCU Medical, which has historically served black, lower income families. Therefore, there is a good chance many black patients and family members have visited this chapel, looking for a place to pray and instead finding plaques honoring a defender of slavery.

It is also important to understand the chapel is not a remnant of the Civil War era but of the Civil Rights Era. In response to the Civil Rights movement, there was a spike in the creation of memorials dedicated to Confederates. This was a way for racists to solidify their power and strength in direct opposition to black people protesting for equality. The darkness and lack of light within felt all too symbolic of how this chapel was a dark stain upon this building and the city of Richmond. There is nothing ‘historic’ about the creation of this chapel. This chapel is not a creation from a past mindset, it is a site that reminds us that Confederate ideology is still entrenched into the present-day fabric of Richmond. “They did not know any better” cannot apply when this memorial was created in the 20th century. The Jefferson Davis Memorial Chapel shows that even though a location is well hidden, and not receiving much attention, it does not take away from the fact that it is still there. There is a need to acknowledge the danger in sites such as these, and remove them from existence, instead of letting them hide away, continuing to perpetuate their harmful ideals by simply being there as a reminder to all that this history is still very much alive.