by Nathan Burns

Nathan Burns is a junior from Newtown, Pennsylvania double-majoring in French and Leadership Studies and minoring in English. This summer of 2019 marks Nathan’s first time working with the Race & Racism Project. On campus, Nathan is also a writing consultant and a member of the dining services student advisory committee.

I find it fitting to begin this blog post at the end of my experience at The American Civil War Museum mostly because of a t-shirt I saw hanging in the gift shop. Blazoned in bold white capitals against black fabric, the shirt read, “I AM MY ANCESTORS’ WILDEST DREAMS”. The phrase stayed with me as I left the gift shop and stepped into the warm summer rain. I stared back at the museum from the outside and marveled at the blend of past and present architecture, noticing the brick ruins of the historic Tredegar Iron Works enveloped by the steel and glass modern design of the current museum. In this moment, I couldn’t help but reflect on our team discussion with public historian Free Egunfemi on the topic of ancestral self-determination. I ask myself now as I write this post: how and where did I see this idea of self-determination at work in the museum’s exhibit? In other words, where did I see resistance against the traditional historical narrative of the Civil War, and how might this resistance inform the ways we remember our past in the present?

I find it fitting to begin this blog post at the end of my experience at The American Civil War Museum mostly because of a t-shirt I saw hanging in the gift shop. Blazoned in bold white capitals against black fabric, the shirt read, “I AM MY ANCESTORS’ WILDEST DREAMS”. The phrase stayed with me as I left the gift shop and stepped into the warm summer rain. I stared back at the museum from the outside and marveled at the blend of past and present architecture, noticing the brick ruins of the historic Tredegar Iron Works enveloped by the steel and glass modern design of the current museum. In this moment, I couldn’t help but reflect on our team discussion with public historian Free Egunfemi on the topic of ancestral self-determination. I ask myself now as I write this post: how and where did I see this idea of self-determination at work in the museum’s exhibit? In other words, where did I see resistance against the traditional historical narrative of the Civil War, and how might this resistance inform the ways we remember our past in the present?

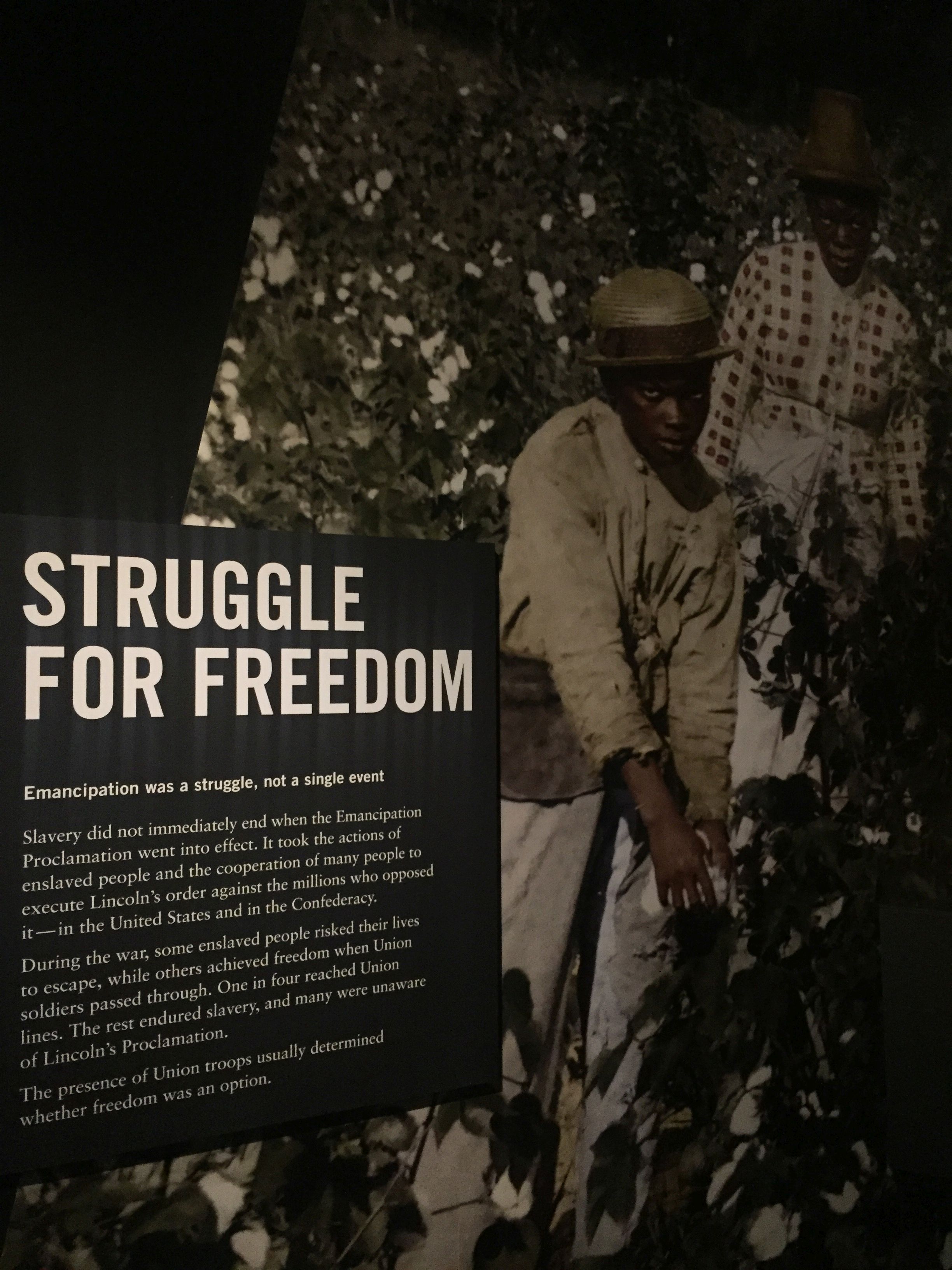

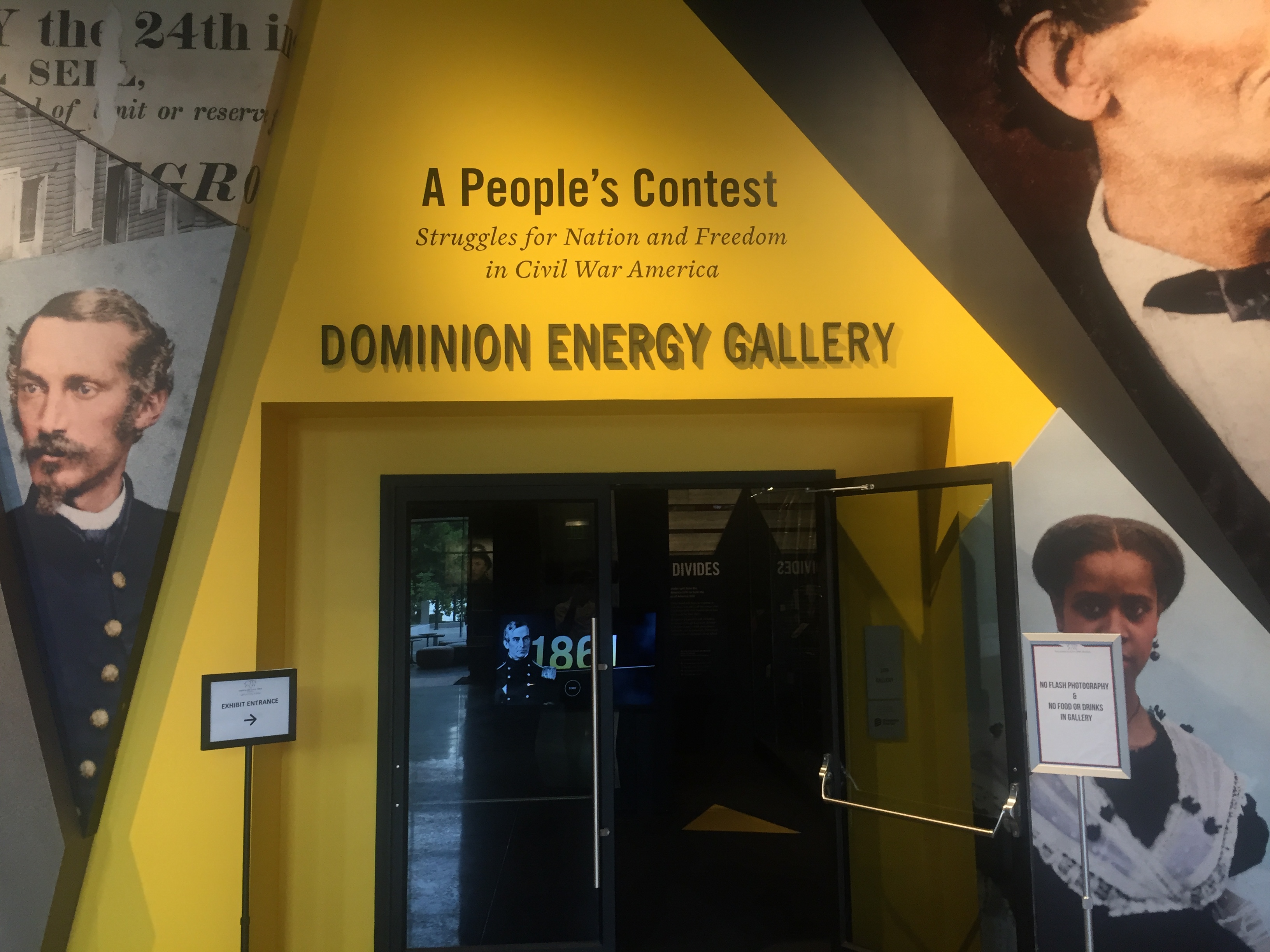

The main museum exhibit, titled “A People’s Contest: Struggles for Nation and Freedom in Civil War America,” organizes the events of the Civil War chronologically in an attempt to portray both the internal and external tensions of many people involved in the war. Whereas I expected the exhibit to focus heavily on the Confederacy (since the museum recently merged with the former Museum of the Confederacy and is located in the former capital of the Confederacy), I was happily surprised by the emphasis on both sides of the war. Furthermore, I appreciated the exhibits portrayal of the complicated struggle for freedom that enslaved Black people on both sides faced during and after the war. The exhibit clearly states that “Emancipation was a struggle, not a single event,” which contradicts the common historical narrative that slavery ended once Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation went into effect. In addition, the exhibit recognizes the manual labor by Black people that fueled the war effort, as well as the contributions of Black troops. It saddens me that this information was never formally taught to me in history classes that covered the Civil War.

The main museum exhibit, titled “A People’s Contest: Struggles for Nation and Freedom in Civil War America,” organizes the events of the Civil War chronologically in an attempt to portray both the internal and external tensions of many people involved in the war. Whereas I expected the exhibit to focus heavily on the Confederacy (since the museum recently merged with the former Museum of the Confederacy and is located in the former capital of the Confederacy), I was happily surprised by the emphasis on both sides of the war. Furthermore, I appreciated the exhibits portrayal of the complicated struggle for freedom that enslaved Black people on both sides faced during and after the war. The exhibit clearly states that “Emancipation was a struggle, not a single event,” which contradicts the common historical narrative that slavery ended once Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation went into effect. In addition, the exhibit recognizes the manual labor by Black people that fueled the war effort, as well as the contributions of Black troops. It saddens me that this information was never formally taught to me in history classes that covered the Civil War.

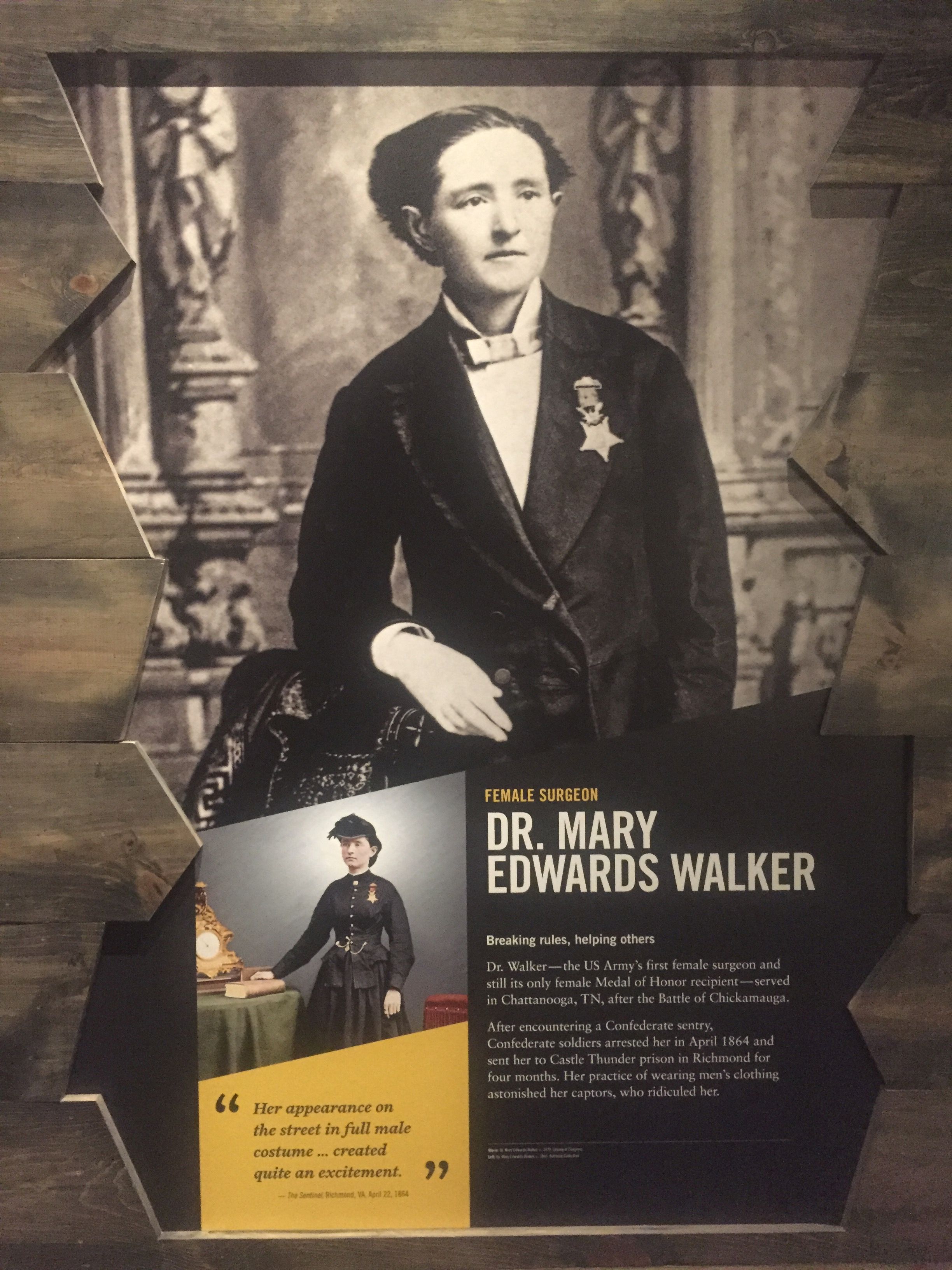

Other sections of the exhibit that resist my understanding of the historical narrative are the Richmond Bread Riots led by women in 1863 and the contributions of Dr. Mary Edwards Walker, the U.S. Army’s first female surgeon and only female Medal of Honor recipient. I had a very limited idea of the roles women played during the Civil War, and learning history from this perspective enriched my understanding of the war in general.

One of the museum’s most striking features is its colorization of photographs from the Civil War time period. Throughout my visit to the exhibit, my eyes poured over images that felt eerily more immediate and even more vivid than I had ever seen before. I understand this choice to colorize the photos not only as an intentional method to attract a present-day audience such as myself, but also as a way to close the distance between now and the time of the war, challenging any idea that the Civil War was an event without impact on our lives today.

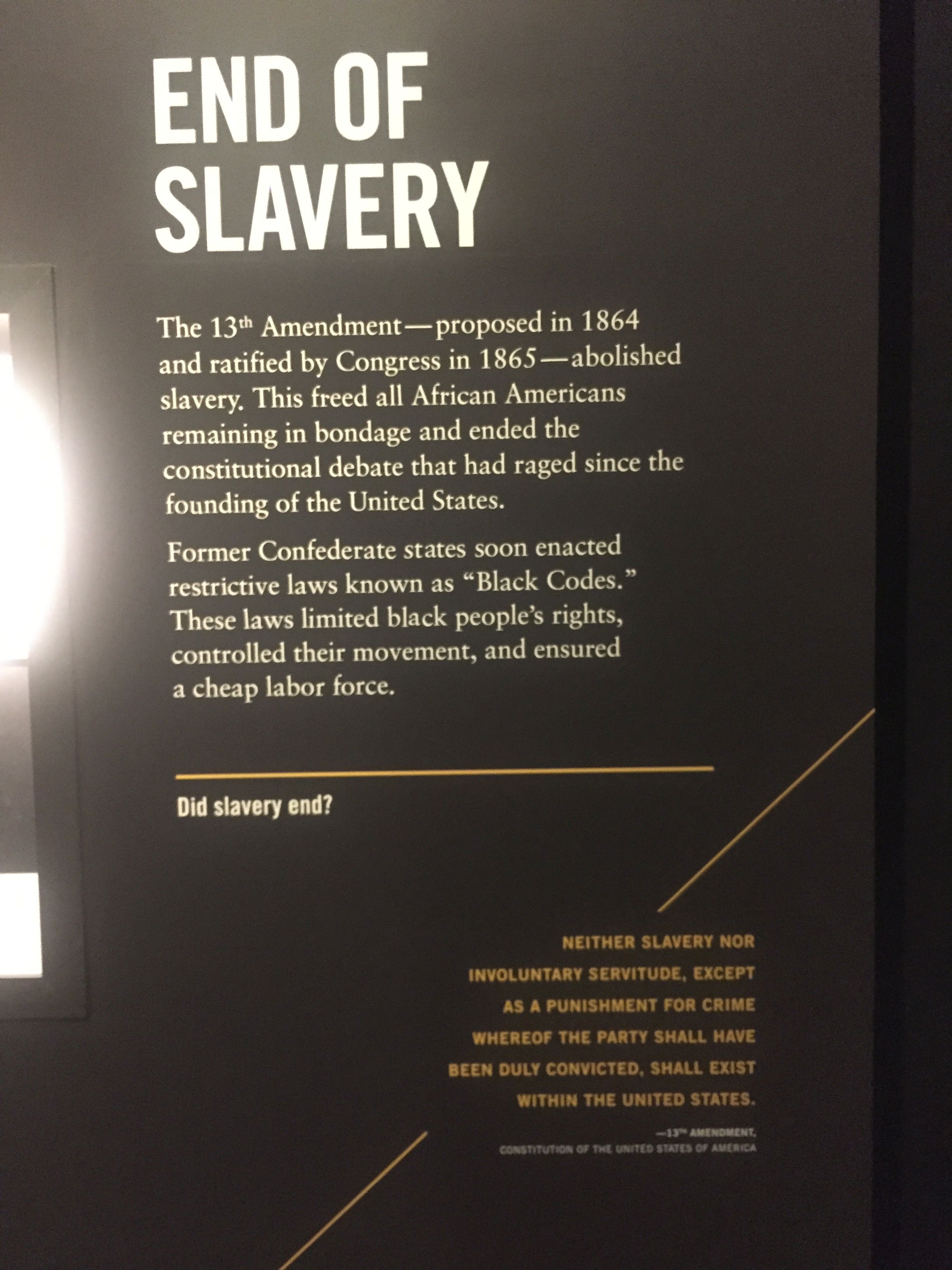

While the exhibit’s strength lies in its resistance to preconceived historical narratives that shaped how I once understood the events of the Civil War, the last room of the exhibit felt, to me, like an abrupt ending to an ongoing history. The room attempts to answer what I believe to be an overarching historical intervention: how exactly should we remember the Civil War? For example, this room houses information about the abolition of slavery with the ratification of the 13th Amendment, while in small print underneath the sign reads the question, “Did slavery end?”

While the exhibit’s strength lies in its resistance to preconceived historical narratives that shaped how I once understood the events of the Civil War, the last room of the exhibit felt, to me, like an abrupt ending to an ongoing history. The room attempts to answer what I believe to be an overarching historical intervention: how exactly should we remember the Civil War? For example, this room houses information about the abolition of slavery with the ratification of the 13th Amendment, while in small print underneath the sign reads the question, “Did slavery end?”

Nathan Burns and Cole Richard at the museum. In my opinion, this section of the exhibit could have been elaborated upon immensely, considering it also holds only a small sign about “Lost Cause” ideology and another on “Memory and Loss”. The exhibit seems to be leading toward these complex questions of how our memory of the Civil War impacts our lives today, yet in this last room, it falls short of going into detail about cultural memory, especially in the city of Richmond. Although I saw room for expansion in the last room, I saw numerous narratives of self-determination at work in the exhibit, which both broadened and complicated what I knew about the Civil War.

In my opinion, this section of the exhibit could have been elaborated upon immensely, considering it also holds only a small sign about “Lost Cause” ideology and another on “Memory and Loss”. The exhibit seems to be leading toward these complex questions of how our memory of the Civil War impacts our lives today, yet in this last room, it falls short of going into detail about cultural memory, especially in the city of Richmond. Although I saw room for expansion in the last room, I saw numerous narratives of self-determination at work in the exhibit, which both broadened and complicated what I knew about the Civil War.