by Gabby Kiser

Gabby Kiser is a junior from Williamsburg, Virginia majoring in English and minoring in History. This is her first summer with the Race & Racism Project. She is also the general manager of WDCE 90.1 FM, a design editor for The Messenger, and a Bunk content wrangler.

On the 17th floor of the VCU Medical Center’s West Hospital rests an unexpected beast. Sure, there’s a plaque in the 1st floor lobby that states the Jefferson Davis Memorial Chapel is just an elevator trip away, but, if I hadn’t done research before showing up, I certainly wouldn’t have anticipated seeing its marble archway behind an unmarked wooden door, sharing the hall with an employee-only restroom and a spattering of what appear to be used waiting-room chairs.

On the 17th floor of the VCU Medical Center’s West Hospital rests an unexpected beast. Sure, there’s a plaque in the 1st floor lobby that states the Jefferson Davis Memorial Chapel is just an elevator trip away, but, if I hadn’t done research before showing up, I certainly wouldn’t have anticipated seeing its marble archway behind an unmarked wooden door, sharing the hall with an employee-only restroom and a spattering of what appear to be used waiting-room chairs.

The bits of information I could find online about this place were from three sources: a fairly recent blog post by Selden Richardson in the Shockhoe Examiner, a response from Richardson to a reader, and a MoveOn petition that appears to have gone online in 2015. There are no tours, no maps, and no information at the site aside from memorial plaques placed by the Daughters of the Confederacy in 1960 upon the chapel’s opening. The room has lights at both end, but its pews lie in darkness. West Hospital doesn’t even hold patients anymore, and narrowly evaded demolition about ten years ago. Still, its chapel is open for whoever wants to see it.

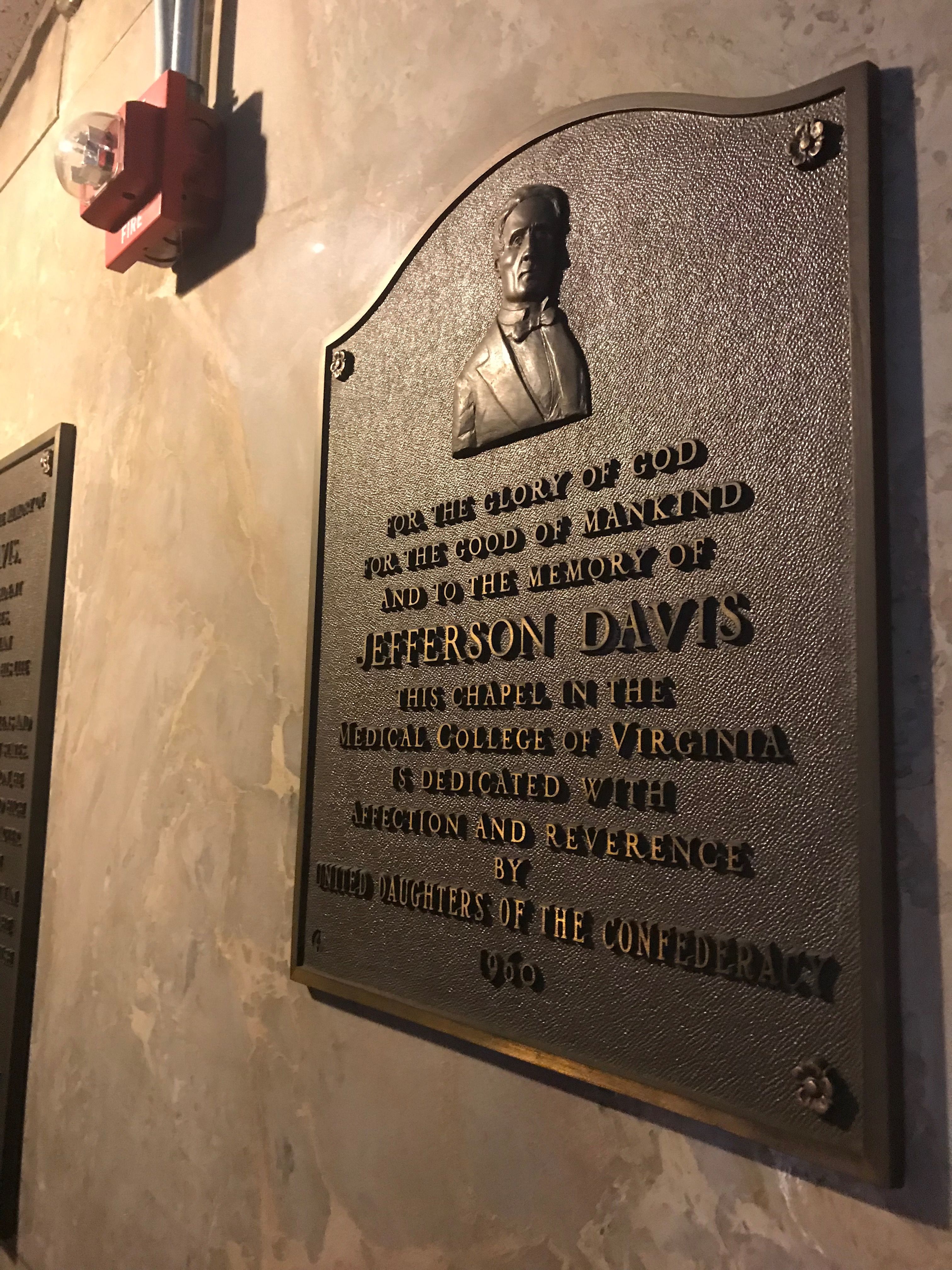

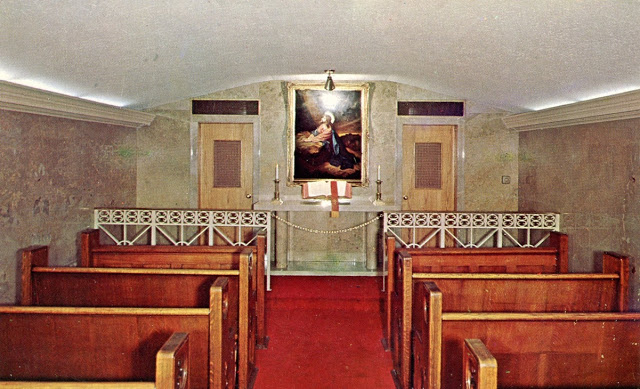

Upon walking through the threshold, I was unable to imagine the hospital chapel as a place of solace or comfort. It is bunker-esque and smells of old carpet, and I explored in the dark because I couldn’t find a light switch. This decorative discomfort takes the back seat, though, when considering the aforementioned plaques. Two are on your right once you walk in, and one is tucked in the left corner behind an electric organ. I first went to my right, as there was no extra light on the left side. The dedication plaque claims that the chapel is placed and named, “For the glory of God[,] for the good of mankind[,] and to the memory of Jefferson Davis.” The chapel’s namesake is depicted on this plaque, his bronze eyes looking out at the dim room before it. Left of this plaque is one explaining Davis’s importance as “American patriot and president of the Confederate states.” One of the most interesting lines of this history claims that Davis “was beloved by persons of low rank and high.” This line either totally ignores enslaved Africans who were forced to live at America’s lowest rank, or idealizes Davis as a champion for them. I moved to the other side of the doorway and, using my phone’s light to read the final plaque, discovered that it’s a tribute to the President-General of the United Daughters of the Confederacy at the time of the chapel’s dedication.

Upon walking through the threshold, I was unable to imagine the hospital chapel as a place of solace or comfort. It is bunker-esque and smells of old carpet, and I explored in the dark because I couldn’t find a light switch. This decorative discomfort takes the back seat, though, when considering the aforementioned plaques. Two are on your right once you walk in, and one is tucked in the left corner behind an electric organ. I first went to my right, as there was no extra light on the left side. The dedication plaque claims that the chapel is placed and named, “For the glory of God[,] for the good of mankind[,] and to the memory of Jefferson Davis.” The chapel’s namesake is depicted on this plaque, his bronze eyes looking out at the dim room before it. Left of this plaque is one explaining Davis’s importance as “American patriot and president of the Confederate states.” One of the most interesting lines of this history claims that Davis “was beloved by persons of low rank and high.” This line either totally ignores enslaved Africans who were forced to live at America’s lowest rank, or idealizes Davis as a champion for them. I moved to the other side of the doorway and, using my phone’s light to read the final plaque, discovered that it’s a tribute to the President-General of the United Daughters of the Confederacy at the time of the chapel’s dedication.

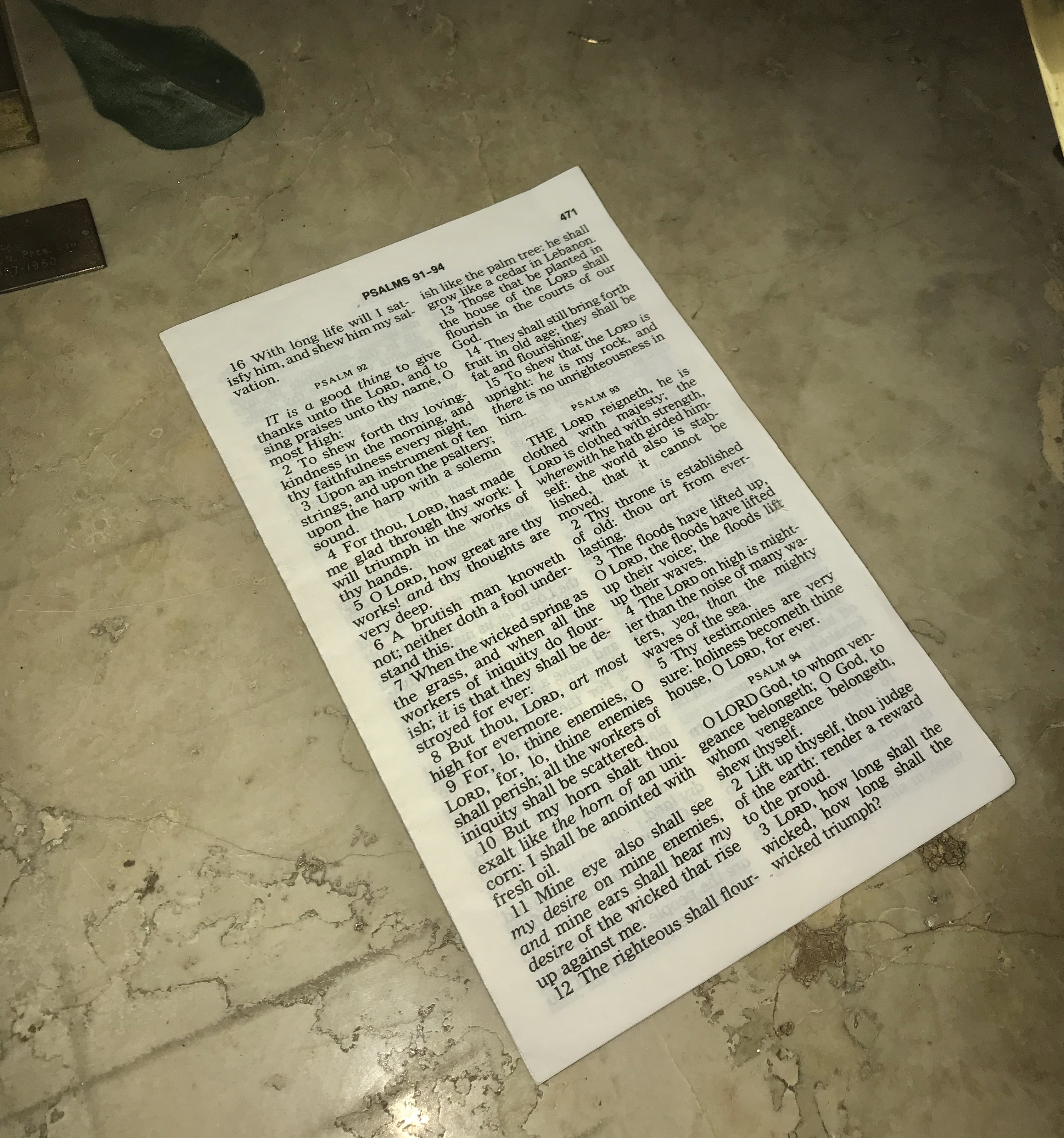

Going further into the dark room, I paid close attention to the illuminated alter. While I noticed that the fake flowers had been changed between Richardson’s visit and mine, the space is otherwise neglected. A few pages have fallen out from the Bible, and bits of faux flowers litter the surface. The electric candles on each end are unplugged. As Richardson notes in his post, the original painting of Jesus Christ behind the alter was replaced over the years by a crude replica.

The VCU Medical Center is a state-owned hospital with a history of catering to economically disadvantaged, often black, people. The presence of a chapel dedicated to the man who led the Confederacy’s fight for the preservation of slavery in any hospital isolates many of those who may use it. The fact that it’s in this one feels even worse. People came to this hospital to receive care that they couldn’t receive anywhere else, and their families and friends followed to show compassion during difficult times. A hospital chapel should help to alleviate the stress of injury and illness. How could a black patient or loved one find comfort or healing in this chapel when Davis’s discriminatory eyes stare into the backs of those in the pews?

At the bottom of one of the fallen Bible pages on the alter is Psalm 94.3, which asks, “Lord, how long shall the wicked, how long shall the wicked triumph?” How long will names and legacies like Jefferson Davis’s be painted as heroic, as adored, as right in the face of those who they served to dehumanize? As I mentioned, there is a petition to change the chapel’s name, and I signed it. Perhaps the Jefferson Davis Memorial Chapel, a monument to ideals of inequality, sits mostly forgotten on top of administrative offices now, but the fact that it’s there at all should be reconsidered.

At the bottom of one of the fallen Bible pages on the alter is Psalm 94.3, which asks, “Lord, how long shall the wicked, how long shall the wicked triumph?” How long will names and legacies like Jefferson Davis’s be painted as heroic, as adored, as right in the face of those who they served to dehumanize? As I mentioned, there is a petition to change the chapel’s name, and I signed it. Perhaps the Jefferson Davis Memorial Chapel, a monument to ideals of inequality, sits mostly forgotten on top of administrative offices now, but the fact that it’s there at all should be reconsidered.