by Ayele d’Almeida

Ayele d’Almeida is a Political Science and Leadership double-major from Bloomington, Minnesota. Her work at Common Ground, the University of Richmond’s social justice initiative informed her decision to pursue the Race & Racism Project as a summer fellow. She hopes that through her fellowship and continued connection with the project, she will learn more about the University of Richmond. Ayele believes that the Race & Racism Project will also help later in life – as the project forces her to question institutions she may benefits from. She hoped to focus her research on black faculty and the presence of black students in white-dominated clubs and spaces.

When Irina Rogova, the Race & Racism Project archivist first presented the list of potential site visits to our group, every site seemed normal except for one — “The Monument to Stonewall Jackson’s Arm.” By normal, I mean that all of the other sites did not memorialize individuals but rather told a story. I had joked to myself saying “I wonder if it’ll be sticking up out of the dirt.” I am not sure what it was that initially drew me to visit the Monument to Stonewall Jackson’s Arm at Ellwood Manor. Thomas Johnathan “Stonewall” Jackson was an America Confederate general during the America Civil War. Ellwood Manor served as a field hospital after the Battle of Chancellorsville. Perhaps it was the mere disbelief that Jackson’s arm was buried separately from his body. It may have even been the fact that his arm was memorialized at all. Regardless of whatever it was, I set out to find out what the fervor was about on June 16th with Mysia Perry, another summer research fellow and Dr. Maurantonio, the Race & Racism Project Coordinator.

When Irina Rogova, the Race & Racism Project archivist first presented the list of potential site visits to our group, every site seemed normal except for one — “The Monument to Stonewall Jackson’s Arm.” By normal, I mean that all of the other sites did not memorialize individuals but rather told a story. I had joked to myself saying “I wonder if it’ll be sticking up out of the dirt.” I am not sure what it was that initially drew me to visit the Monument to Stonewall Jackson’s Arm at Ellwood Manor. Thomas Johnathan “Stonewall” Jackson was an America Confederate general during the America Civil War. Ellwood Manor served as a field hospital after the Battle of Chancellorsville. Perhaps it was the mere disbelief that Jackson’s arm was buried separately from his body. It may have even been the fact that his arm was memorialized at all. Regardless of whatever it was, I set out to find out what the fervor was about on June 16th with Mysia Perry, another summer research fellow and Dr. Maurantonio, the Race & Racism Project Coordinator.

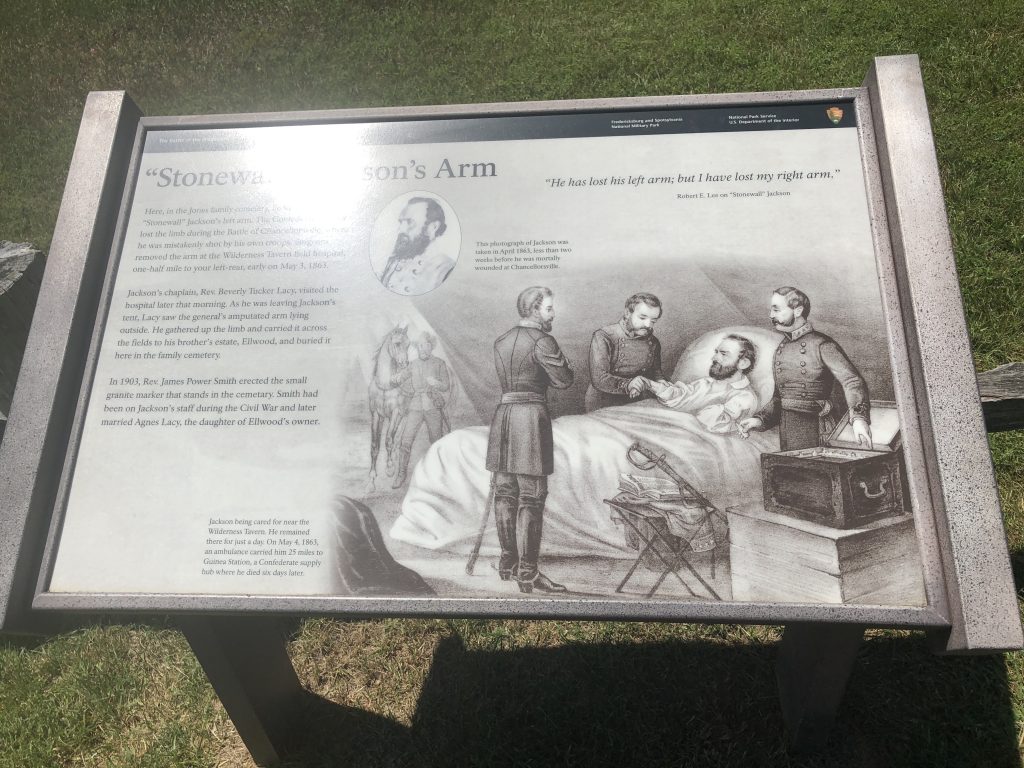

When we eventually arrived, we were greeted by a woman who gave us a brochure of some upcoming events at Ellwood. The list included a medical re-enactment of Stonewall Jackson’s arm amputation. The woman also recounted the story of the arm burial: a day after the amputation, Rev. Tucker Lacy saw Jackson’s arm laying outside of the medical tent. In an effort to preserve the dignity of the revered general, he buried the arm in his family’s cemetery at Ellwood. When Jackson eventually died, Lacy asked his wife, Mary Anna Jackson, if she wanted to bury her husband’s arm with the rest of his body. To this, she responded by asking if the arm had had a Christian burial. When Lacy said yes, Mrs. Jackson insisted that the arm could stay in the Lacy family cemetery. Forty years after this happened, Reverend James P. Smith erected a small granite marker where the arm was buried. This stone is the only marker in the entire family cemetery. The absence of grave markers for members of the Lacy family was perplexing as there seemed to be more importance put on Jackson’s arm than on deceased family members.

When we eventually arrived, we were greeted by a woman who gave us a brochure of some upcoming events at Ellwood. The list included a medical re-enactment of Stonewall Jackson’s arm amputation. The woman also recounted the story of the arm burial: a day after the amputation, Rev. Tucker Lacy saw Jackson’s arm laying outside of the medical tent. In an effort to preserve the dignity of the revered general, he buried the arm in his family’s cemetery at Ellwood. When Jackson eventually died, Lacy asked his wife, Mary Anna Jackson, if she wanted to bury her husband’s arm with the rest of his body. To this, she responded by asking if the arm had had a Christian burial. When Lacy said yes, Mrs. Jackson insisted that the arm could stay in the Lacy family cemetery. Forty years after this happened, Reverend James P. Smith erected a small granite marker where the arm was buried. This stone is the only marker in the entire family cemetery. The absence of grave markers for members of the Lacy family was perplexing as there seemed to be more importance put on Jackson’s arm than on deceased family members.

The monument itself was very modest. The granite slab jutted out with a slant: “Arm of Stonewall Jackson May 3, 1863” read the marker. It was enclosed by a wooden fence. The site was situated in a large field and in between rows of an undetermined crop. Despite the signage and the story of the burial, Dr. Maurantonio, Mysia, and myself sensed that there was an aspect of the story that did not add up. Perhaps it was Jackson’s wife agreeing to bury her husband’s arm separately from his body. It may have even been the fact that on what was meant to be a family burial plot, Jackson’s arm was the only marked grave. When we left Ellwood, we were puzzled by these questions.

Something that I can say is that having Dr. Maurantonio and Mysia at the site encouraged me to question what I was being told. I suppose this is what the Race & Racism Project is about — constantly questioning stories that have been passed down to us. In many cases, as we’ve seen in the archives, there are details or people left out in order to hide or bury truths. The visit to the Monument to Stonewall Jackson’s Arm reinforced my faith in the work we are doing for the Race & Racism Project. The memorialization of Jackson’s arm brings up the ongoing question of who we should be remembering as heroes. I would imagine that the individuals visiting the arm as well as the plantation had a vested interest in the preservation of the history of the Confederacy. Although I believe that it is rather important to acknowledge our history, I believe that this needs to be done in a way that steers away from idolizing certain figures or aspects that represent dark times in our history.